How Wuhan and the coronavirus are shaping China’s medical reforms

- Digital solutions and the private sector are key to the success of the next stage of Beijing’s health care reforms

- Family medicine and general practitioners will play a pivotal role as the country aims for a mature health care system by 2030

Wuhan was already a cause for concern among doctors long before it became synonymous with the novel coronavirus pandemic. The central Chinese city of 11 million people was foremost on the minds of the 3,600 family doctors attending a conference in Zhengzhou, the capital of neighbouring Henan province to the north.

It was still only March 2019 and the gathering, a meet organised by the Cross Straits Medical Association and backed by the World Organisation of Family Doctors, came to the conclusion that Wuhan, the biggest city in central China, was in urgent need of health care reform. Its already overburdened hospitals needed to be augmented and supported by a network of clinics, which would function as first ports of call for patients. The reforms could even serve as a blueprint for other parts of China.

The not-for-profit professional organisation could not have been more prescient. Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, which has infected about 1.6 million people worldwide and claimed more than 95,000 lives, was first reported in Wuhan in December 2019.

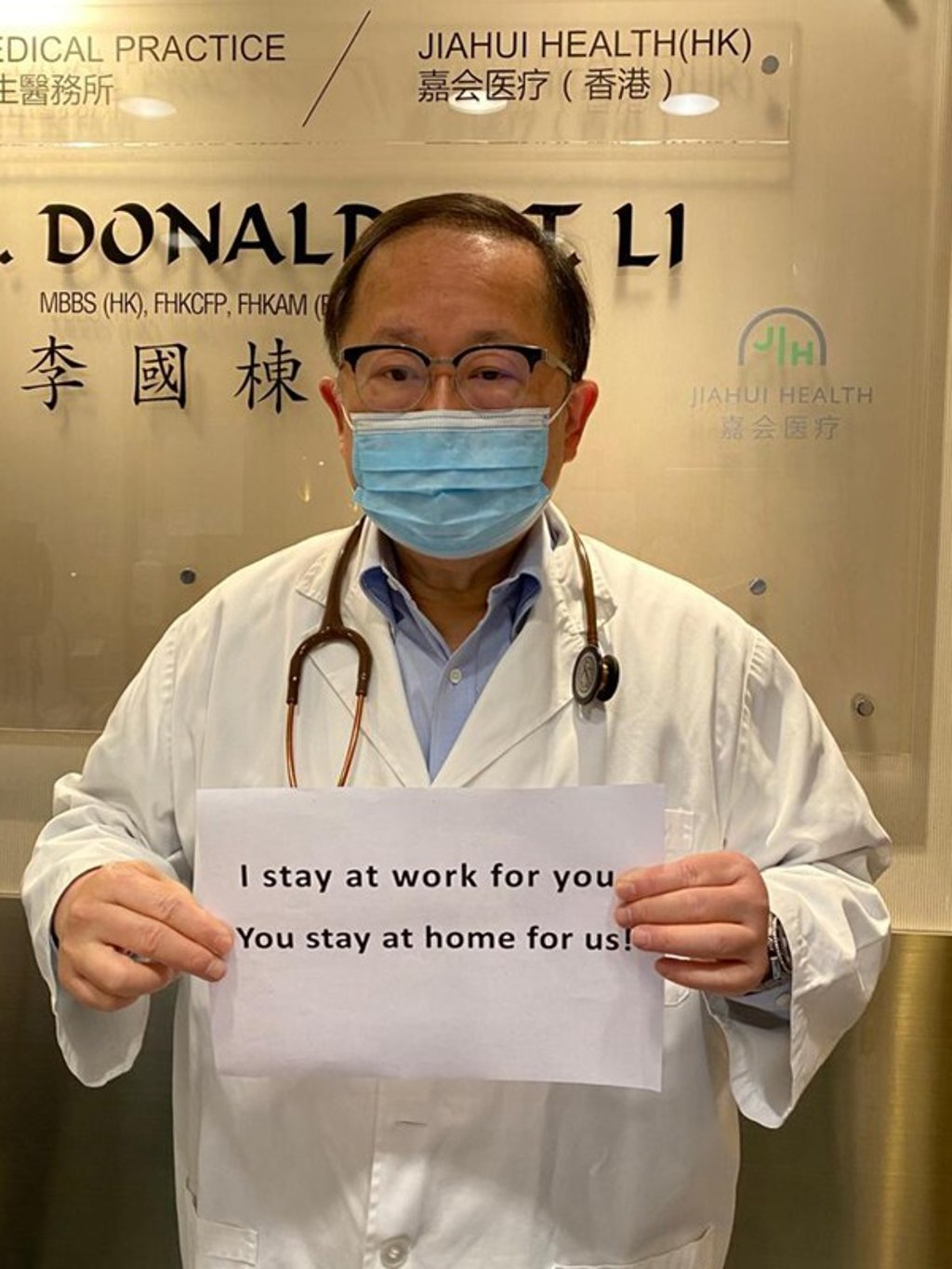

“The primary care infrastructure in Wuhan was comparatively not up to standard, [and] awareness among residents of public health care was relatively low,” Donald Li Kwok-tung, the organisation’s Hong Kong-based president, said in an interview. “The surge of patients rushing to hospitals quickly overwhelmed the entire system in Wuhan and in surrounding cities, and infected patients seeking treatment helped to spread the virus more quickly in the process.”

And as the pandemic tapers off in Wuhan and mainland China, a blueprint has in fact emerged, which is being followed by governments across the globe: entire cities have been locked down, travel restrictions have been put in place and the production of medical items ranging from ventilators to hand sanitisers has assumed paramount importance.

And eyes will once again be on Wuhan and China, as they pick up the pieces and carry out reforms with the aim of avoiding another such outbreak.