Companies rush to replace ‘just in time’ supply chains with ‘just in case’ contingencies as Covid-19 upends global manufacturing

- Industry players and supply chain experts said the shifting of the supply chain model is most likely in the production of essential goods such as food and medical devices

- Even as some firms look to disentangle their production networks from China, the country’s role in the global supply chain is too big to be replaced, say analysts

QYK Brands was putting the final touches on its US$5 million medical mask production line in Garden Grove, California, when it hit a snag: export shipments by its Chinese supplier of melt-blown polypropylene – the non-woven mesh that filters out airborne particles – were disrupted by extra inspections. China is its only source of supply, since all of the US fabric production combined can barely meet the needs of the largest face masks manufacturer in the country.

Supplies from Sinopec, China’s largest petrochemical producer and Chinese resellers of its products, trickled almost to a complete stop in early April, as Chinese customs inspectors scrutinised every overseas shipment of medical supplies and devices to ensure they meet export quality and protect China’s global reputation.

“There are plenty of suppliers in China, but only Sinopec is reliable [because] the rest are middle men buying and reselling it while marking the price up three to four times,” QYK’s chief executive Rakesh Tammabattula said in a telephone interview with South China Morning Post. “What’s more, there is no way we can authenticate the filtration effectiveness of the fabric because we cannot impose any requirement to test the products before they are delivered … we have to take the quality risk.”

Many companies had already moved or mulled the idea of shifting manufacturing facilities out of China after it became embroiled in a gruelling trade war with the US.

“It takes 2,500 components to make a car, but just one component to not make a car,” said Madhur Jha, head of thematic research at Standard Chartered in India, who led a May 5 report on the pandemic’s impact on global supply chains. The consequences of the disruptions in global manufacturing “is leading to a renewed focus on the concentration risks inherent in supply chains,” he said. “Some companies are likely to accelerate trends that were already under way, shortening and simplifying supply chains.”

South Korea’s automotive industry knows all too well the consequences, after the most important part of its supply chain turned into a choke point that throttled three of the country’s five carmakers. Hyundai Motor suspended all production in February for a week because it ran out of a crucial wiring component after a worker at its supplier’s factory caught the coronavirus in China, forcing the entire plant to shut. Ssangyong Motor halted its Pyeongtaek assembly for a week, also because of the shutdown by Chinese suppliers. Kia Motors, the second-biggest South Korean carmaker, reduced its output in Hwaseong and Gwangju for the same reasons, according to local media reports.

The same stories were repeated across the spectrum of manufactured products, from clothing to electronics and toys.

The problem is pushing companies to consider a “just in case” supply chain to augment the “just in time” model that had served the world in the past four decades. This is particularly the case for producers of essential goods such as food and medical devices, while the pandemic is destroying lives and livelihood.

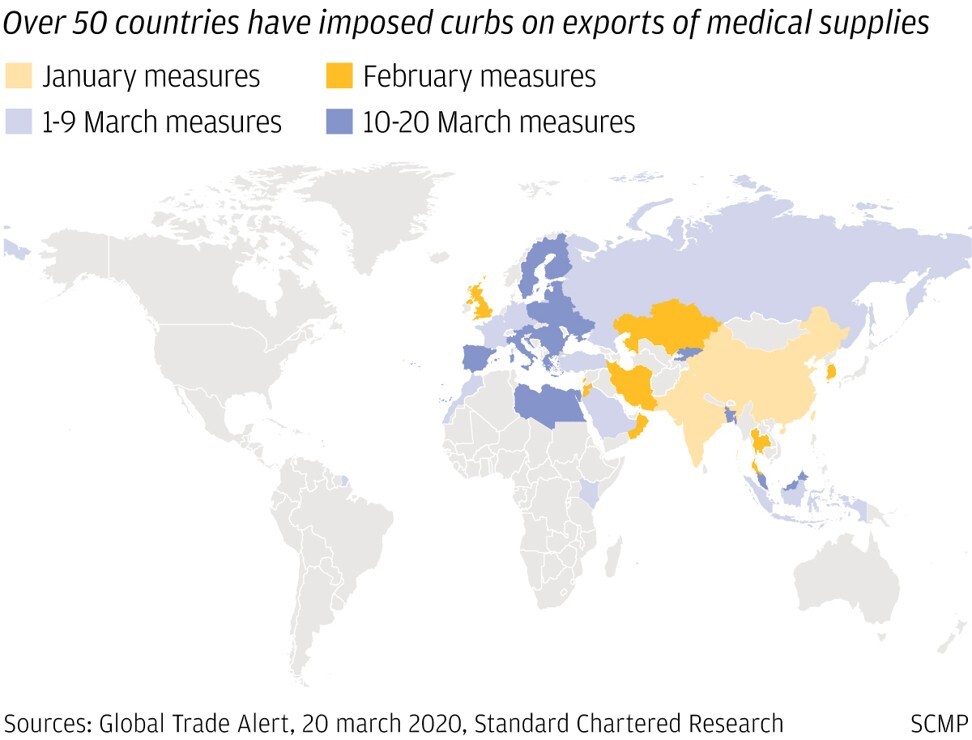

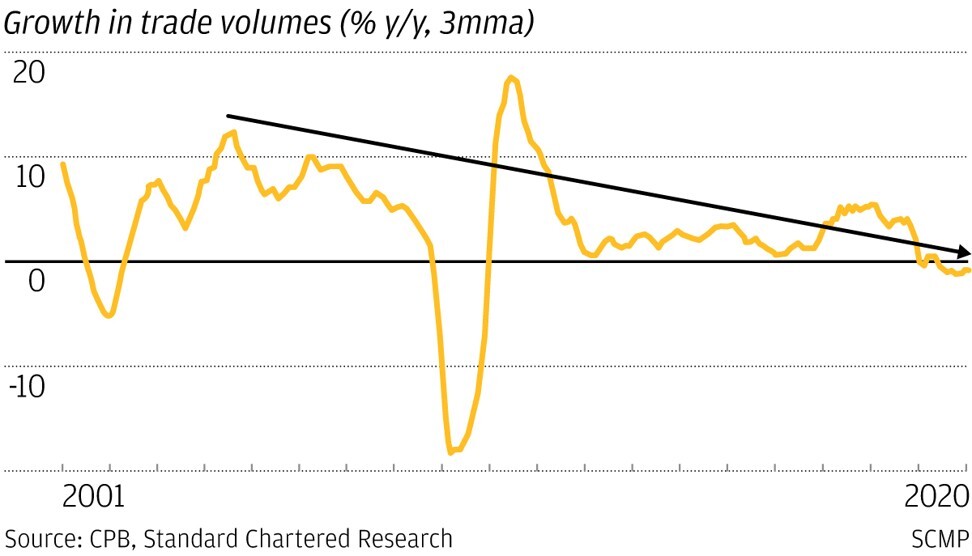

Global trade has gradually declined since the global financial crisis. Average annual growth in volumes dropped to 2 per cent between 2013 and 2019, well below the 5.9 per cent average from 2001 to 2007. The significance of supply chains within global trade has also diminished, according to Standard Chartered Bank.

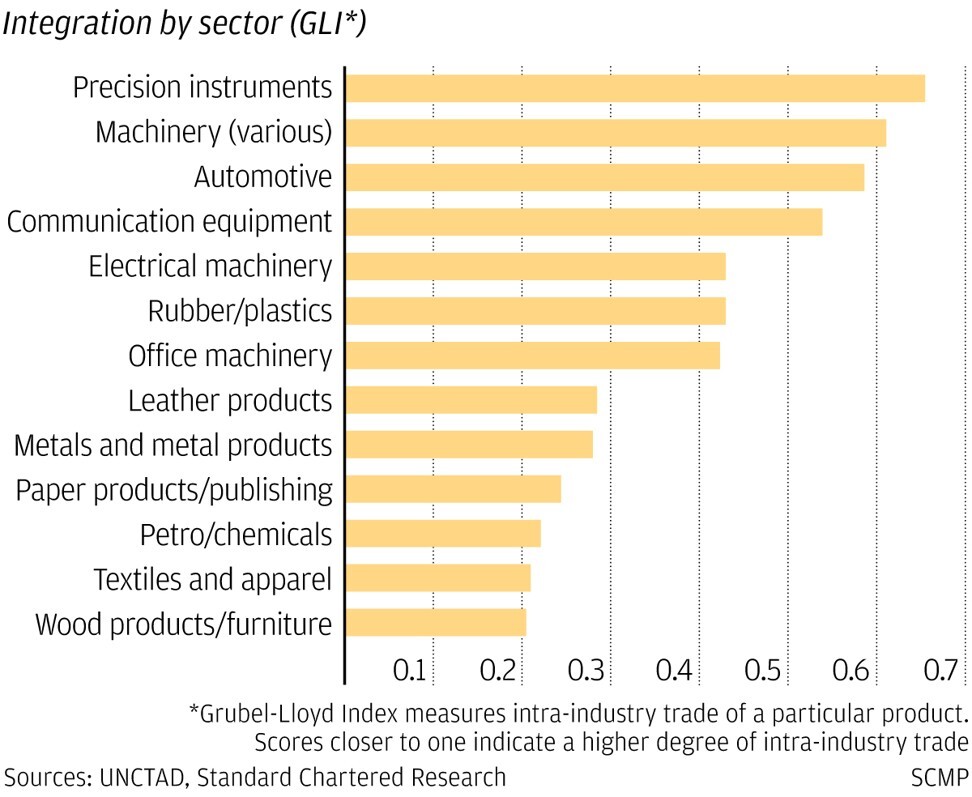

China accounts for more than half the global supply chains of several manufacturing products, including precision instruments, cars, communications equipment, and machinery products, according to a report citing an analysis by The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Reuters reported in early May on a concerted push by the US’ Commerce Department, State Department and other agencies to look for ways “to remove global industrial supply chains from China”.

In the past few weeks, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro has been talking about an executive order that would require government agencies to only buy US-made medical products.

In Japan, the government announced in early April that it would spend up to US$2 billion to help its firms move production out of China, and US$200 million for companies moving production to other countries.

However, industry players and supply chain experts said the shifting of the supply chain model is more likely to occur in the manufacturing of essential goods such as food and medical devices.

Ongoing decentralisation of manufacturing bases from China to other countries may expand, but China’s role in the global supply chain is too big to be replaced.

“Manufacturing with a decentralised supply chain, and the decentralised stocking points and everything else has been evolving over time,” said John Pearson, chief executive officer of DHL Express in a phone interview from Bonn, Germany. “The whole ‘just in time’ and ‘just in case’ type of set-up may have a veneer of adjustment in someone’s supply chain, but not a lot has happened … because we see China firing up, and then Asia, and then Europe.”

Dependent on China? How Japan wants to tackle the coronavirus disruption

The key factors are efficiency and economics.

While shipping out of China does not help amid the global pandemic, decentralisation of manufacturing bases, or decentralised source of procurement will expand to mitigate future risks.

“Back in February, when China was locked down, people said ‘Can we move to overseas?’ In March, people said ‘China is opening up, can we move back to China?’ When it comes to global lockdown, there is no safe place,” said Roger Lee, chief executive of TAL Apparel.

TAL Apparel, which makes one of out of every six dress shirts in the USA for brands like JC Penney, Brooks Brothers and Eddie Bauer, does not expect to see any significant changes in the supply chain network in the fashion industry.

But having more than one country as a manufacturing base is always a “safe bet,” said Lee of TAL, which makes shirts, blouses, trousers and suits for the American and European markets. It has production facilities in China, Ethiopia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Stanley Szeto Chi-yan, chairman of Hong Kong-listed apparel supply chain manager Lever Style, said ongoing relocation of procurement sources – much of it from China to Southeast and South Asian countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam to reduce costs – will be expanded to hedge against future supply risks as retailers learn to put their eggs in more than one basket.

His company, which a decade ago made all its products in China, now has just over a quarter of its products made there, about half its volume comes from Vietnam, and the rest from Cambodia, India and Indonesia.

Even in cases where companies plan to move out of China, it will take them three to five years to complete the relocation, said Kerry Logistics group managing director William Ma Wing-kai.

“China’s role is unlikely to be reduced rapidly,” said Ma.

“Take the US-China trade war issue as an example. It began in the first quarter of 2018, then we saw some companies start moving facilities in the third quarter of 2018 to avoid extra trade tariffs. “Manufacturing facilities in Asian countries such as Vietnam weren’t seen until the third quarter of 2019. It took two years to move manufacturing bases. The lead time is long and the costs are high.”

Again, technology could emerge as a disrupter.

Increasingly rapid advances in robotics have raised the efficiency of manufacturing. Robotics offer both higher output per unit time and higher accuracy for repeatable tasks than human labour, said Jha of Standard Chartered Bank.

“The advancement of robotics and automation has enabled high-cost destinations to bring low-skilled manufacturing back onshore from low-cost offshore centres,” she said.