Exclusive | Hong Kong textile firm Esquel to keep its Xinjiang factories open despite US sanctions threat over ‘forced labour’ accusations

- Esquel is one of six companies singled out for potential sanctions in US draft legislation regarding forced labour in Xinjiang

- The Hong Kong textile firm will defend itself and keep factories running, CEO says, while China retaliates with sanctions on US politicians

The coronavirus pandemic caught Esquel and many of its global fashion rivals off guard this year, but the 42-year-old Hong Kong-based textile manufacturer is facing an even bigger challenge: the US government.

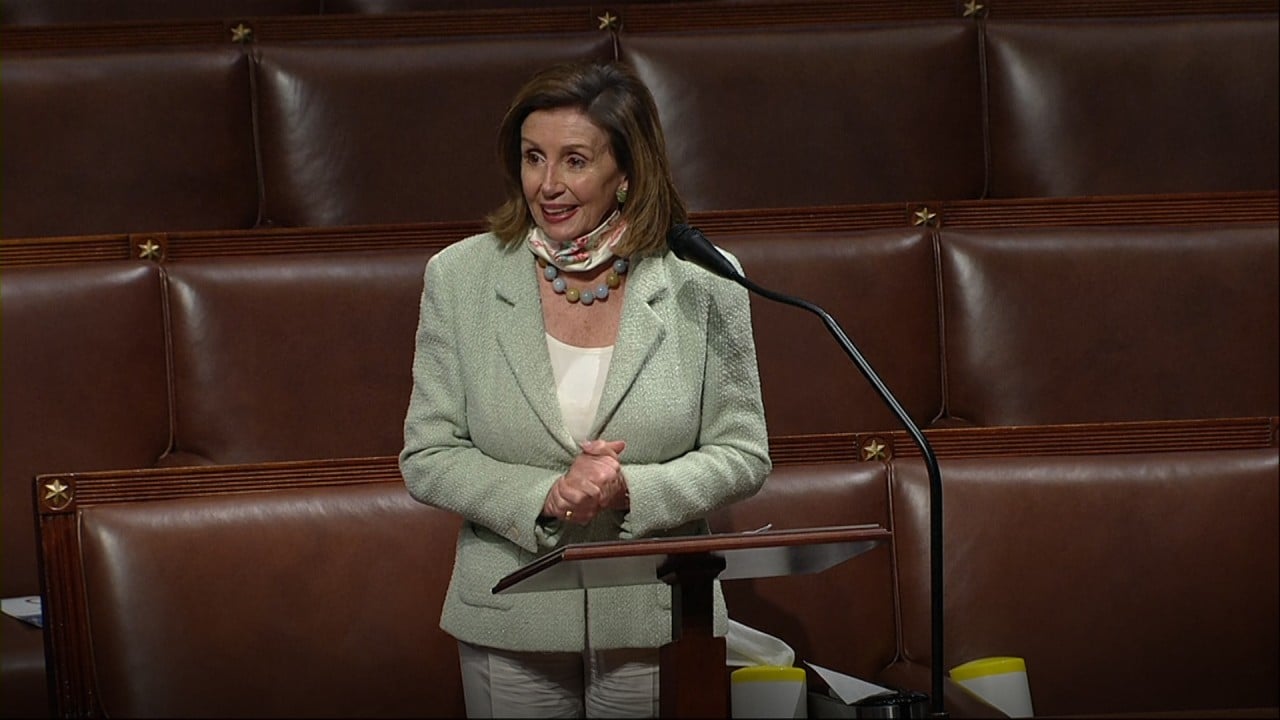

03:21

US House of Representatives sends Uygur Human Rights Policy Act to Trump’s desk for approval

“It could have a big impact on us if the bill is passed,” said John Cheh, vice-chairman and chief executive of Esquel, which has achieved US$1.3 billion in revenue and produces more than 100 million garments annually, about a third of them shipped to its US clients.

But instead of shrinking from the challenge, Esquel will defend its stance and prove its innocence, said Cheh.

The company will keep its manufacturing plants running in the autonomous region, even as it finds itself in the cross hairs of US sanctions, he said.

“Yes, we could probably get the issue settled if we give in and close our plants. But if we do so, it may imply that we admit the accusation. We absolutely do not use forced workers of any kind,” Cheh said in an interview with South China Morning Post.

China vows ‘reciprocal action’ against critics of Xinjiang policies after US sanctions move

“We have not done anything wrong. We need guts and strength of character [to persevere on] the issue,” said Cheh.

The legislation calls for goods produced by Esquel and a group of Chinese manufacturers to be subject to a so-called withhold release order (WRO), a measure where US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) can block imports if the agency has “reasonable suspicion” the items were made by forced labour.

Importers of goods subject to a WRO have to prove to US Customs on a shipment-by-shipment basis that they were not made wholly or in part by forced labour, according to John Foote, an international trade partner at the law firm Baker McKenzie in Washington. That proof is needed not just for the final manufacturer, but extends throughout the entire supply chain, he said.

Beijing has repeatedly dismissed these criticisms and said the camps are to give Uygurs the training they need to find better jobs and stay away from the influence of radical fundamentalism.

01:09

China claims most Muslim detainees have left Xinjiang re-education camps and returned to society

Esquel has three spinning mills, established in the region in 1995, 1998 and 2009, respectively. It also has two cotton ginning mills built in 2003, which separate raw cotton fibre from seed parts. Over the years, the company has invested about US$160 million.

Those are not the largest manufacturing bases among the company’s production facilities. Other plants in Foshan in southern China, and in Vietnam are bigger in terms of investment scale and total number of workers. But Xinjiang has its strategic positioning for Esquel.

At the end of last year, their spinning mills in Xinjiang had a production capacity of 200,000 spindles of cotton, one per cent of the 20 million total capacity in the region.

“Esquel did not take any workers offered by the Xinjiang government as news media reported,” Cheh said, referring to an article by The Wall Street Journal in May last year.

“Even if an agent introduces applicants to us, we will interview them, and consider them only if the qualifications and skills meet our requirements.”

All workers are free to leave whenever they want to, no matter the reason, he said.

Big name brands accused of using Uygur ‘forced labour’ by Australian think tank

Esquel has 45,000 staff in total, with 1,343 employees of different ethnicities in Xinjiang. Of those workers, 420 staff members are Uygur.

Cheh said the company does not take any subsidies from the government to hire workers. The average monthly salary for its workers is more than 4,000 yuan (US$572) per person, 2.5 times the minimum wage of 1,620 yuan in Xinjiang.

When Esquel was singled out in the draft legislation fours months ago, the company was not notified. Now, Cheh hopes that Esquel will get a chance to present evidence to prove its innocence.

But the road could be bumpy.

“The ‘reasonable suspicion’ standard constitutes a relatively low bar for the imposition of a WRO,” Foote, the Baker McKenzie lawyer, said. “By contrast, the burden of proof to obtain relief for goods impacted by a WRO is correspondingly high. For an importer to prove a negative – to prove that individual goods were not made wholly or in part by forced labour – is really an extraordinarily high burden of proof.”

A manufacturer facing a WRO would have to ask US Customs to revoke the order by presenting evidence it does not use forced labour, but the procedure to do so is not straightforward and the decision-making process behind those orders is not transparent, Foote said.

“There is no formal review process by which CBP evaluates the continued applicability of WROs. Once a WRO is issued, it can remain in effect indefinitely,” Foote said.

The oldest active WRO in place dates back to 1953 and relates to furniture made by inmates at a prison in Mexico.

Like other apparel manufacturers, Esquel’s businesses was hit hard as its US clients faced restrictions on social interactions and stores were shut down amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The company closed three facilities – one in Ningbo in the Zhejiang province of China, and two in Malaysia – and will close another one in Mauritius by the end of July. The closure of the four factories means axing 10,000 workers in total, bringing Esquel’s total headcount to 45,000.

Digitalisation the way forward for global apparel makers post-pandemic

As part of a business diversification strategy, the company started producing reusable antibacterial cotton masks for staff and customers in mid March.

It has sold 35 million masks since March, over 10 million of them to the Temasek Foundation of Singapore. The foundation recently started distributing a pair of antimicrobial face masks to every resident of Singapore.

Esquel is also branching out into wellness products such as face scarves for clients as consumers become more health conscious after the pandemic.