Exclusive | New World’s Harvard-educated scion upends Hong Kong developers’ ‘build and sell’ business model as city sits at crossroads

- Adrian Cheng Chi-kong, a third-generation scion of the family that controls New World Development, is charting a different course as Hong Kong stands at a crossroads

- The 41-year-old father of three wants to engage with stakeholders through innovation, culture and artistry

Cheng Yu-tung, one of Hong Kong’s best-known tycoons, spared no expense when he led a 1985 effort to build a harbourfront convention centre to host the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty 12 years later.

Construction activity on the US$322 million project was a gesture of confidence in a city clawing its way out of recession, buffeted by the exchange of barbs between Chinese negotiators and the city’s then colonial master, Britain.

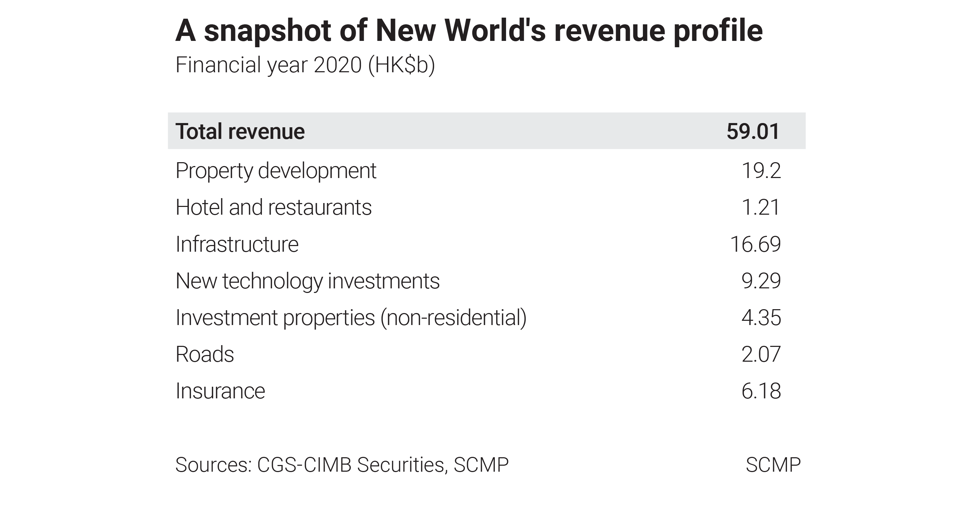

This time, the late magnate’s eldest grandson Adrian Cheng Chi-kong is charting a different course to restore the community’s confidence. New World Development, a HK$102 billion (US$13.2 billion) conglomerate of 44,000 employees working in a range of cradle-to-grave businesses that touch on everything from education and health care to property and insurance, is evolving, said Cheng, who turned 41 in November.

“Developers usually focus on how to increase gross floor area and maximise profits. We also make profits and we gain premiums [for shareholders], but we have a balance,” said Cheng, a father of three, in an interview with South China Morning Post. “We are still a property developer, but we are a developer of hardware and software services that enrich our customers’ lives.”

Cheng took over in May as chief executive officer of New World from his father, further cementing his position in the group. He is part of the third generation of entrepreneurs now taking the reins of some of Hong Kong’s largest business empires. His grandfather built the empire out of the family’s mainstay jewellery business.

“In the next 10 years, nobody will ask [which developers] are the biggest or smallest, but rather they will care about their social impact on society,” Cheng said. “Previously, we might have focused on the rankings of companies. But even if you are the richest developer, so what? Audience and customers do not care.”

To engage with the new generation of customers, he is digging deep into his tertiary education where his appreciation of the arts and culture of China, Japan and Korea are being fused into a business model which involves selling New World’s mainstay property. A “human-centric” approach can help unravel the complexities of a new generation of consumer behaviour and make New World more sustainable and powerful in the future, he said.

“From there, we can create many ideas in property developments and services to elevate living quality,” said Cheng. “Our business model can be relevant [to society] in the next 30 years.”

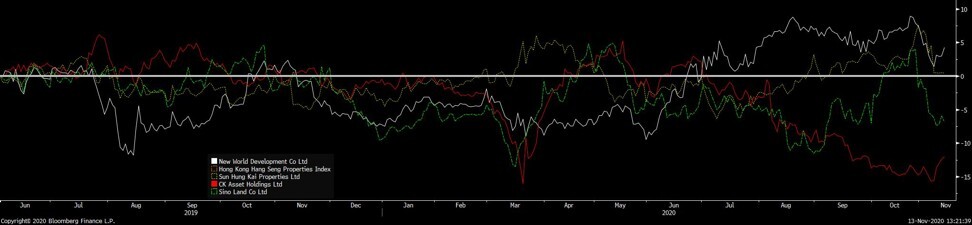

The disruption appears to be paying off, in a real estate market that’s struggling to find its footing after a year of unrest and amid a recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

New World’s sale of The Pavilia Farm, the developer’s first mass housing project since 2018, sold out in three successful rounds of weekend launches in Tai Wai, putting it on track to report HK$10 billion in revenue from its first 1,000 apartments.

That would be a record for the developer, in a year weighed down by a global coronavirus pandemic and the Hong Kong’s worst recession in history.

“Fifty per cent of our buyers of the project are below 40 years old,” said Cheng, who sees it as proof that millennial customers are buying into his business model and share his values.

The 3,090-unit project, whose first phase is slated for completion in 2022, emphasises energy saving and a provision of land on the property for growing crops, as more millennials take a stand on climate change and energy issues.

“Many features were designed by ourselves to enrich modern living, such as a built-in retractable clothes rack and foldable ironing board that saves space,” Cheng said.

Still, the new business model has yet to fully translate to improved financial results. New World reported an underlying profit for the year ended June of HK$6.6 billion, which was 16 per cent below consensus, partly because it had not completed any major property projects in Hong Kong in the period.

Gross rental income rose 19 per cent during the year, despite a challenging operating environment amid the global coronavirus pandemic, driven by the start of operations at K11 Musea and the K11 Atelier in Tsim Sha Tsui, two of the group’s 23 major property projects in Hong Kong. The group owns the Hyatt Regency, Renaissance and Novotel hotels in Hong Kong. The exhibition centre, built by the late magnate Cheng, reported a record HK$25.92 billion in revenue in the 2019 financial year, just before street rallies and protests and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic disrupted Hong Kong’s status as a convention hub.

The Musea shopping centre and the 26-storey Atelier office building bear Cheng’s signature style of fusing functionality with style through an art gallery, installations and sculptures in public areas. He created the K11 brand in China during the late 2000s when he was given the free hand to run and turn around the New World Department Stores in mainland China. The stores’ operating income, little changed before he took over, more than doubled in 2007 when he took the helm, soaring to a record HK$766 million in 2012.

In the Shenyang store in north-eastern China’s Liaoning province, washrooms were bedecked with slate and installed with the latest designs in taps, and decorated with contemporary patterns, a Cheng signature that sought to give the shopper a different feel and usage experience from competitors. He even bothered to place live greenery in the washrooms.

“Among the third generation of property empires in Hong Kong, Adrian [Cheng] is brave and innovative,” said Ken Yeung, head of Hong Kong property research at Citi. “The idea of the ecosystem of the group’s businesses he described to analysts two years ago are now visible. On top of property, New World provides education, health care and insurance, which the company can cross-sell through the help of big data once they’ve locked in a group of loyal customers.”

The conglomerate has a host of businesses to provide just that cross-selling. New World Services, 61 per cent owned by the developer, provides health care with Parkway Pantai’s Gleneagles Hong Kong Hospital, and offers insurance via FTLife Insurance.

Cheng also runs two private investment ventures from his base in Hong Kong: one investing in fashion and lifestyle start-ups and the other in cutting-edge technology such as artificial intelligence, big data and virtual reality.

But big investments come at a commensurate price. New World’s net gearing towers over all other developers in Hong Kong, at 39 per cent, including more than US$2.5 billion in spending, according to Raymond Cheng, head of Hong Kong and China research at CGS-CIMB Securities.

One of Cheng’s biggest bets is a HK$20 billion bid won in May 2018 to build a shopping and entertainment complex called the Skycity near Hong Kong’s airport. The complex, boasting 3.77 million square feet in area including Hong Kong’s largest shopping centre, is expected to open in phases between 2023 and 2027. Its development was set in motion before the year-long anti-government protests in Hong Kong drove away mainland China’s tourists and shoppers.

Another core asset is its commercial development, Victoria Dockside on the waterfront of Tsim Sha Tsui at a cost of US$2.6 billion.

New World has sufficient saleable resources to meet its attributable contracted sales target of HK$20 billion per year from 2021 to 2023 in Hong Kong, said Cheng of CGS-CIMB, which has an “add” recommendation on the stock, with a price target of HK$48.

The company completed HK$10.6 billion worth of noncore property and non-property asset

disposals this year. It has set a higher target for asset disposal, of HK$13 billion to HK$15 billion, in the current financial year to fund its expansion in both Hong Kong and China.

“We have witnessed changes in New World, from the ‘build and sell’ style of his grandfather and father to a model that focuses on after-sales services and engagement with stakeholders,” said Cheng. “This came since Adrian took over the company.”

Hong Kong’s property tycoons have amassed the lion’s share of the city’s wealth. But they have also been accused of discouraging competition and prioritising profits over consumers’ interests.

“People always look for quick answers. What is the return on investment? What is the internal rate of return? But experimentation of a successful business model takes time,” Cheng said.

For now, his approach has won over some analysts. Meanwhile, he has the strong sales of New World’s latest The Pavilia Farm project to keep shareholders happy.

“Hongkongers are sick of the developers’ way of increasing gross floor area to maximise their profits. At least Adrian wants to do something different, and I cannot see that ambition in other developers,” said Ronald Chan, chief investment officer at Chartwell Capital, a local investment management company. “Is it just for show, or a genuine vision to contribute to society? At least he is aware of how society is changing and reacts to what the city is looking for.”