CATL’s EV battery breakthrough holds promise as cost-effective, game-changing alternative the industry’s waiting for

- CATL makes rapid progress on sodium-ion batteries, improving the performance of the alternative technology to the mainstay lithium-ion batteries

- The commercialisation of sodium-ion batteries is still some time away, as it will take time to fine-tune products that are a viable option to lithium-ion, say analysts

The first of a three-part series on battery packs looks at the world’s largest producer CATL and how it occupies the apex of a technological revolution to assemble cheaper and more durable cells to power electric cars.

Ningde in southeastern China’s Fujian province, known primarily for its tea plantations, seldom rolls off the tongue in automotive circles or the technology industry.

But on a rainy Friday in late May, the city of fewer than 3 million people was the epicentre of a major technological breakthrough, one that could shake up the world’s supply of battery packs, giving China the technological and competitive edge in providing cheap and durable power source for driving electric vehicles.

“Some people [said] it would be hard to make breakthroughs in the chemistry of batteries, and that improvements can only be made in their physical structures,” Zeng told 170 of CATL’s biggest shareholders, including China Merchants Bank and Hillhouse Capital, during the company’s annual general meeting. “By using a high-throughput calculation platform and simulation technology … [we] continuously evolved and enabled sodium-ion batteries to enter the fast track to industrialisation.”

Zeng’s announcement was music to the ears of not only CATL investors, whose value has topped 1.2 trillion yuan (US$189 billion) with a 41 per cent jump in its stock price this year, but also makers of EVs, or new-energy vehicles (NEVs) as they are called in China.

Most NEV batteries – from the ones assembled by CATL to packs produced by Panasonic and Samsung – rely on lithium and cobalt as the key raw material, both of which are concentrated in a small number of nations.

Amid surging demand for battery packs, led by the popularity and surging production of EVs, the world’s supply of lithium is heading for a “serious supply deficit” by 2027, which could hamper the production of an estimated 3.3 million NEVs that year, according to a forecast by the energy research firm Rystad Energy.

By contrast, sodium is readily found and is virtually inexhaustible.

Global EV sales reached 3.1 million units last year, an increase of 30 per cent from 2019, according to Fitch Ratings. They are expected to make up 45 per cent of the global car market by 2040 compared to 4 per cent last year, the rating agency predicted.

The commodities market has already priced in lithium’s expected tightening of supply. The prices of battery-grade lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate have both more than tripled in the past year to over 160,000 yuan (US$24,850) a tonne.

01:25

Electric bus bursts into flames, sets nearby vehicles on fire in China

Facing looming shortages, global carmakers and battery producers have been seeking alternatives to the dominant lithium-ion batteries.

Sodium-ion batteries also have the added advantage of fast charging and higher performance under low temperatures compared to lithium-ion ones.

CATL claimed its first-generation sodium battery can be recharged to 80 per cent of capacity in 15 minutes at room temperature. At minus 20 degrees Celsius, it loses less than 10 per cent of the energy after it is fully charged, according to the company.

The next-generation product’s energy storage density is expected to exceed 200 Watt-hours per kg, up from 160Wh of the first-generation prototype, Zeng said. Watt-hours are used as a measure of power output.

This range is comparable to those achieved by lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, one of two main types of lithium-ion batteries. NCM, the other product that uses nickel, manganese and cobalt in different ratios, has a higher capacity ranging from 240Wh to 350Wh per kg.

Tesla cars, which use LFP and NCA (nickel cobalt aluminium) batteries, can be charged in 15 minutes at certain fast-charging stations giving them a 200-mile (320km) range, but normal charging gives only 44 miles of range per hour charged.

Sodium-ion is also one of the novel battery technologies earmarked for support by the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s top economic planning agency. Faster development of energy storage is part of the nation’s strategy to both enhance energy security and achieve decarbonisation.

Still, analysts said it will take years to commercialise sodium-ion batteries, while potential customers wait for more progress and details.

“Large scale adoption of sodium-ion batteries commercially is highly unlikely within the next two to three years,” said Dennis Ip, head of utilities and renewables research at Daiwa Capital Markets. “We see the development of sodium-ion batteries as more of a hedge against potential lithium shortages or cost hikes.”

To be sure, even if sodium-ion technology promises cheaper batteries in the future, their performance and mass market launch timing, remain unknown. Their lower energy-storage capacity could also require other battery components to achieve the same power performance, adding to the costs.

While these factors will be mitigated eventually by cost savings as production scale is ramped up, analysts have cast doubts on the suitability of sodium-ion batteries for EVs.

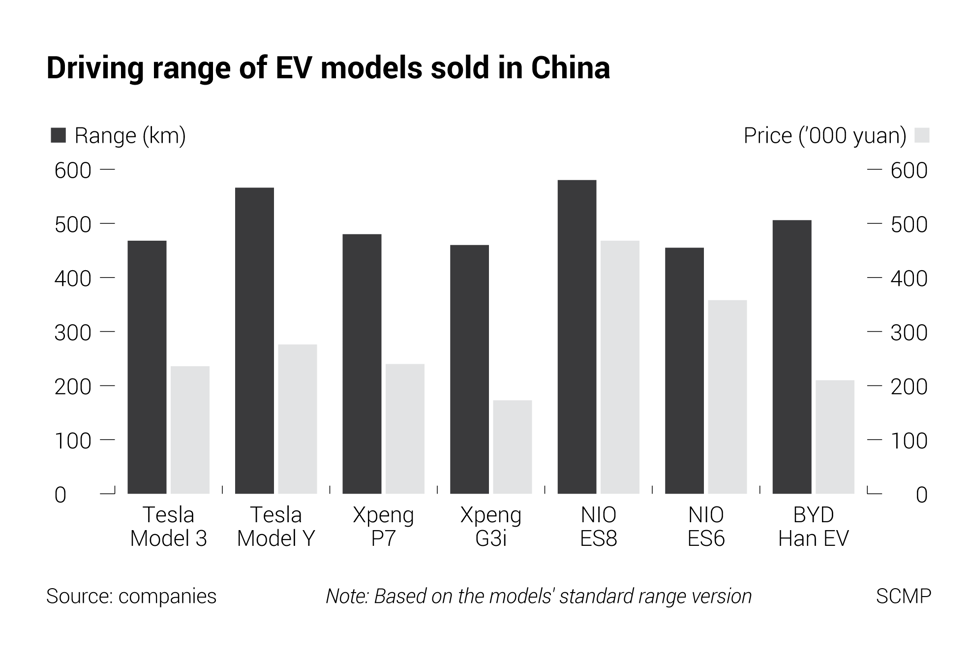

“Their low energy density – even when combined with some lithium-ion battery cells – raises concerns over driving range and hence appropriateness for certain markets,” said David Merriman, manager of battery and EV materials at Roskill.

Does China lead the electric car battery industry?

One thing going for sodium-ion batteries is that will definitely be less sensitive to the rising metal costs – a major concern for lithium battery makers – because of sodium’s widespread availability.

If the price of each of the key battery materials rises by 10 per cent, the material costs of sodium-ion batteries only increase by 0.8 per cent, much lower than the 3.2 per cent for LFP batteries and 4.6 per cent for NCM batteries, analysts Le Xu and Max Reid at Roskill’s parent Wood Mackenzie, wrote in a blog last month.

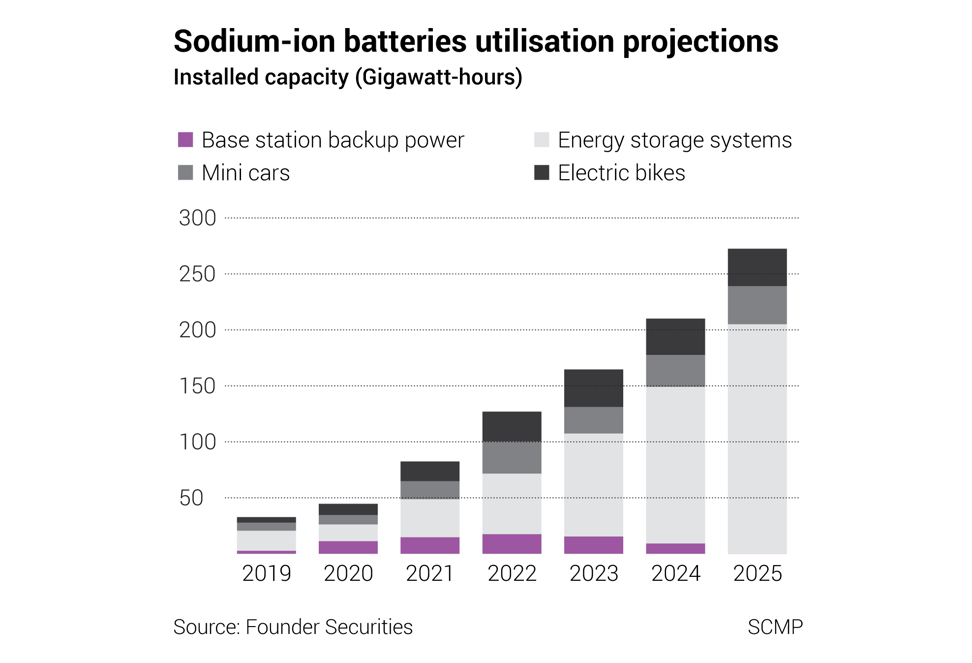

They see sodium-ion batteries as a niche product, chipping away at some of LFP batteries’ share in the EV and energy-storage systems markets and reaching 20 gigawatt-hour in sales by 2030.

Founder Securities’ analysts have a rosier outlook, predicting 33GWh of sodium-ion batteries to be deployed in minicars and 205GWh in energy-storage systems by 2025.

Those predictions are in sharp contrast to the burgeoning global lithium-ion battery production capacity, which may double to 1,447GWh by 2025 from 706GWh this year, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

CATL originally started out as a licensed manufacturer in 2011, before developing its own technology. Riding on the global NEV boom, CATL quickly expanded production from Fujian to four other Chinese provinces – Qinghai, Sichuan, Guangdong and Jiangsu. It started production at its first overseas plant in Germany this year, and five years earlier opened a research centre in Munich.

CATL is not the only company exploring sodium-ion technology in China. In 2017, HiNa Battery Technology, a spin-off of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Physics, became the first Chinese firm to look into the technology.

Jiangsu-based HiNa demonstrated its maiden product in a low-speed mini electric car in 2018. It aims to develop a more competitive alternative to the pollution-causing lead-acid battery used in 90 per cent of such vehicles used mostly in rural areas.

The battery’s energy density reached 145Wh per kg, over five times that of lead-acid batteries.

Sheffield, Britain-based Faradion – set up a decade ago – was the world’s first company dedicated to sodium-ion batteries development, according to a Founder Securities report.

It is demonstrating the use of sodium-ion batteries in low-cost transport such as electric bikes and scooters.

A year ago, California-based start-up Natron Energy launched a pizza-box sized battery pack for use in data centres and telecoms firms, but they are yet to commercialise a product for EVs.

It will take several years for sodium-ion batteries to be designed, tested and approved by end users into commercial-scale products, Roskill’s Merriman noted.

“Whether sodium-ion technologies will be viable alternatives in an increasingly competitive electric vehicles market, displacing lithium-ion and potentially solid-state technologies [in] mass-produced vehicles is unclear,” he said.

“Li-ion [will] remain the dominant technology in EVs through to the end of the decade.”

Additional reporting by Daniel Ren in Shanghai