China’s property crisis: who and what will save the indebted developers in the world’s largest real-estate market?

- Sunac, which forked out 43.8 billion yuan in 2017 to help Wanda, defaulted on a US dollar bond last week, and had its rating cut twice by Fitch, deep into junk status

- R&F, which bought 77 Wanda hotels for 19.9 billion yuan in 2017, had to sell its London asset at a 42 per cent discount

One day mid-July in 2017, one of China’s wealthiest men called a hastily organised media conference to announce what would turn out to be the largest corporate bailout in the country amid a regulatory crackdown on profligate deal making.

Wang dropped a bombshell that day. He sold 77 hotels to R&F for 19.9 billion yuan (US$3 billion). Sunac, under the Chinese bank regulator’s spotlight for its leveraged buyouts, scaled back the commitment it made nine days earlier by 31 per cent, agreeing to pay Wanda 43.8 billion yuan for 13 tourism-related projects, including theme parks.

China property: how the world’s biggest housing market emerged

China’s US$1.7 trillion residential property market is the world’s largest, about seven times bigger than the US market in 2019. It contributed to one in four urban jobs in 2019 among state-owned and publicly traded companies, the National Bureau of Statistics said.

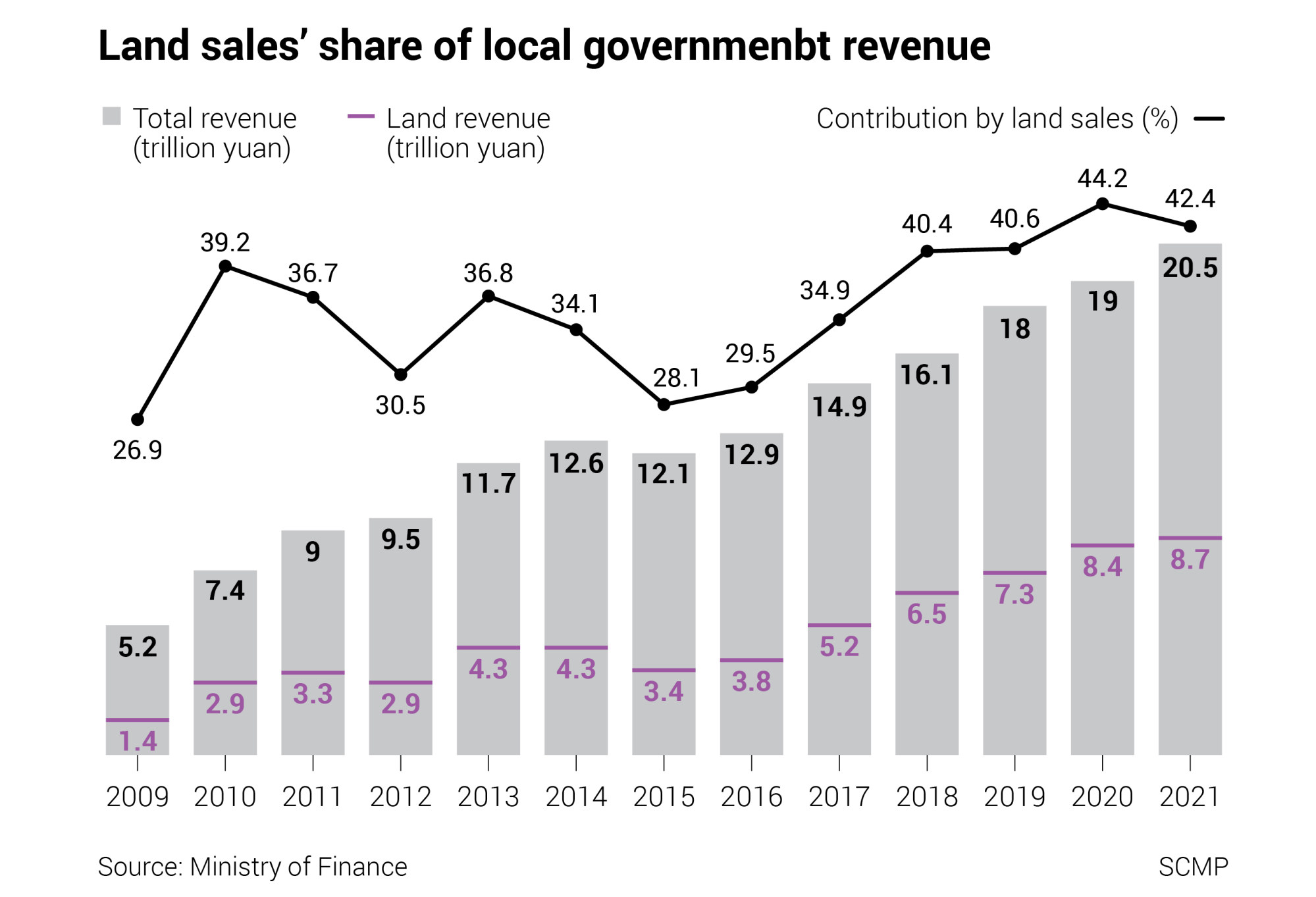

“Considering how the pocket of local governments is spookily exposed to the property market, land sales in particular, the authorities do have the incentives to revive the sector,” Wu said.

Harbin, the provincial capital of northeastern China’s Heilongjiang, was the first to step in, after its first-quarter revenue from land sales plunged by 40 per cent, and the average home price dropped by 20 per cent.

Authorities began releasing presale funds held in the Harbin government’s escrow accounts in October to relieve cash-flow pressure and drum up activity in the dormant housing market. That was followed in March by the removal of a three-year holding period for new homeowners.

Harbin, grappling with one of the highest urban unemployment rates in China’s rust belt, is the epitome of how local authorities have vested interest in the property market. Land sales contributed 8.7 trillion yuan to the coffers of local authorities across China last year, making up 42 per cent of their revenue, excluding funding from the central government in Beijing.

Land sales contributed more than tax receipts to local coffers in more than 20 large and medium-size cities last year, according to the Shenzhen-based advisory firm GoguData.

“Any slump in land sales will send a shiver down the spine of many executives, especially when the long expected property tax did not [materialise] as a new source of government income,” Wu said.

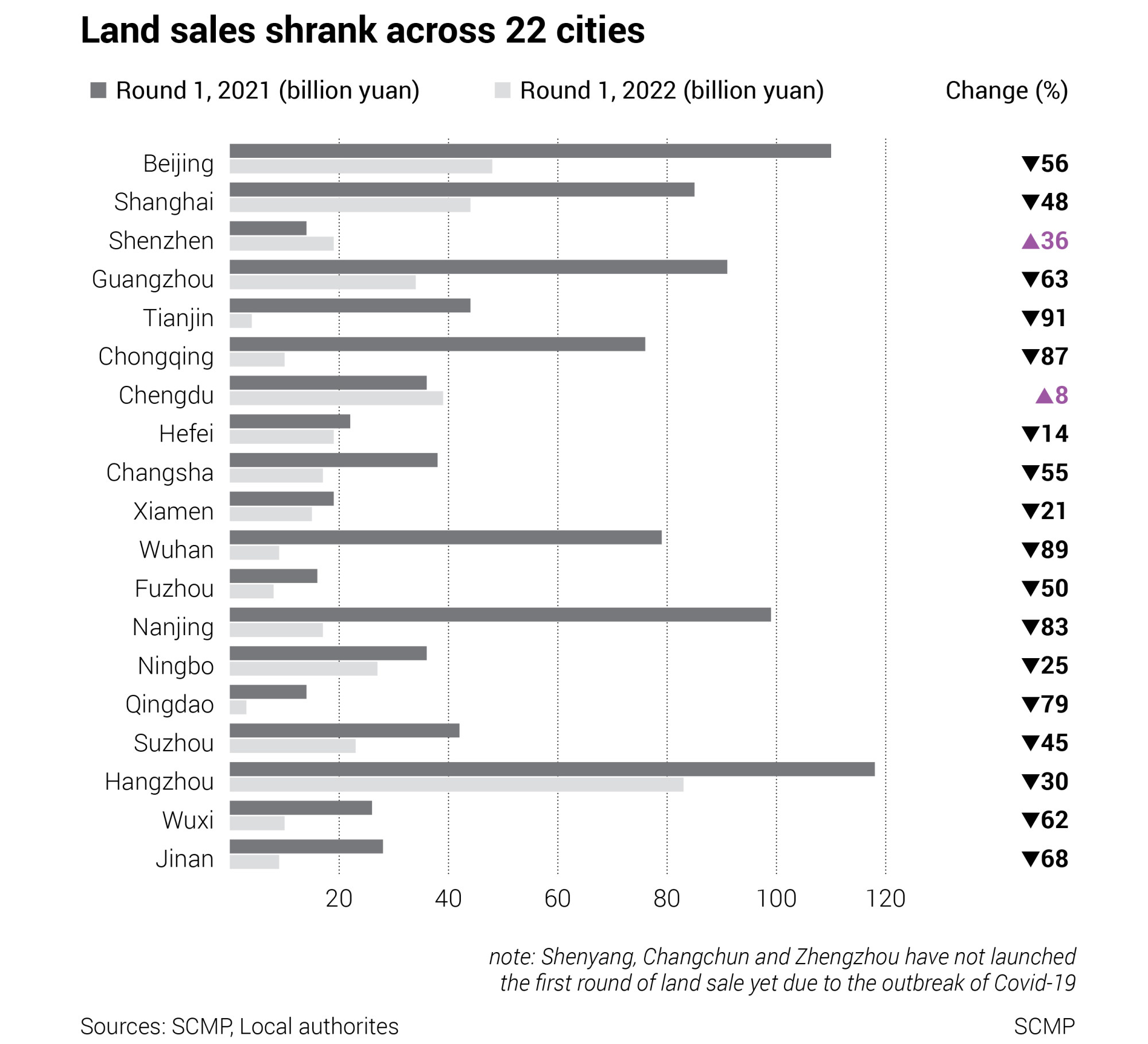

Sales fell in the first three rounds of centralised land auctions everywhere in China this year except Shenzhen and Chengdu.

Tianjin, the port city near Beijing, sold 4 billion yuan of land this year, 91 per cent less than last year, the biggest plunge among major cities. First-quarter economic growth in the city, which hosts a Toyota Motor assembly plant and a chip foundry formerly owned by Motorola, barely registered at 0.1, the second worst performance out of 34 provincial-level governments.

“Most private [developers] are reluctant to spend money on big-ticket [purchases] like land, as their primary task now is to deliver homes on time and pay debts,” said Wang Qi, co-founder of MegaTrust Investment (Hong Kong), a boutique China asset manager.

Only three private developers out of 50 bought land last year: Longfor Group in Chongqing, Shanghai-based CIFI Group and the Hangzhou developer Binjiang Real Estate Group.

“We do not expect them, even the healthy ones, to buy much land or expand aggressively as every single developer needs to prepare for a down cycle worsened by the Covid-19 lockdowns,” said Wang, who publishes Daily Reflection on China, a research note about investments in China.

The choke hold combined with a market that was already beaten down by strict rules since 2017 to rein in runaway prices. As a result, developers could not sell homes to generate cash, causing bond defaults and missed payments to pile up.

Ten months later in May, Sunac became the 18th developer to default when it failed to pay its interest on an offshore bond.

Sunac cited weak contracted sales that were “significantly affected by the recent Covid-19 outbreak” as the last straw that broke its financial strength, in its filing to the Hong Kong stock exchange last week.

“It [may] take at least another month for homebuyers to be convinced that things are back to normal, which is what developers need for their financial troubles to truly begin to ease,” Gavekal’s Rosealea Yao and Zhang Xiaoxi wrote in a May 10 research note.

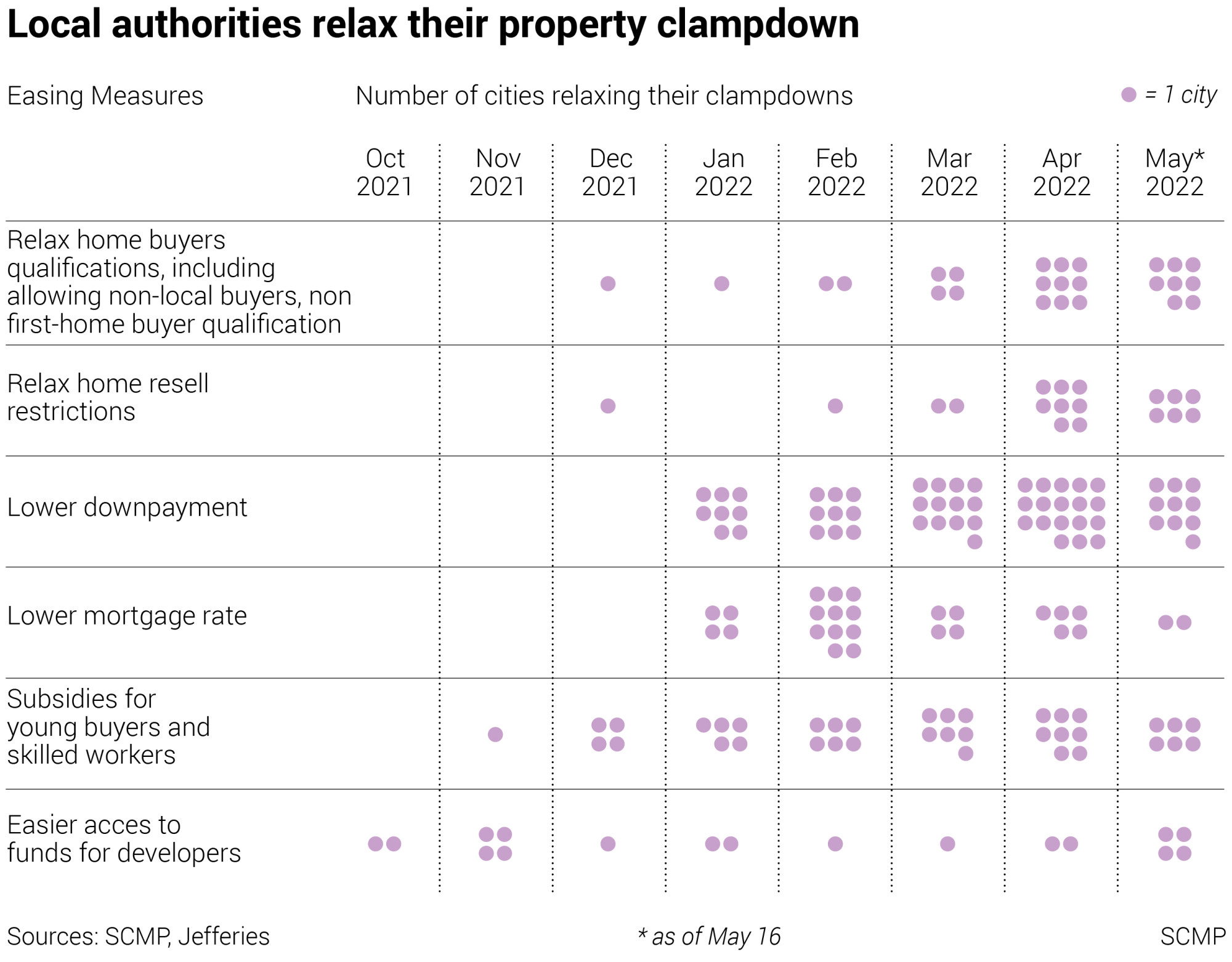

To rekindle demand, the central bank cut the lower limits of interest rates for first-time homebuyers by 20 basis points in May, an ultra strong signal of saving the sector from sinking.

Between last October and May, more than 130 cities relaxed 180 rules on property purchase and sale, granted better mortgage borrowing rates and faster procedures, or handed out direct subsidies to young families. Some launched more than one round of easing policies.

Is Evergrande too big to fail?

Before the lockdown, some Shanghai districts shortened the waiting period for young homebuyers from two years to three months. Sales of new homes declined four months in a row, plummeting 92 per cent since January.

‘Just in time’ morphs into ‘just in case’ as Covid-19 cuts supply chains

Shenzhen’s new home sales declined for the ninth month in a row in April. “We will see more aggressive saving measures by even more local governments to save the sluggish sector,” said Li Yujia, chief researcher at the provincial residential policy research centre of Guangdong.

Are all these moves enough to avert a collapse in China’s property industry?

“I honestly do not know when things will get better, and I have to say it is much tougher than everyone in this sector expected last year,” said Albert Yau, chief financial officer of Zhongliang Holdings, which is struggling with two bonds worth a combined US$750 million.

April sales by the Shanghai developer fell 71 per cent to 4.1 billion yuan from a ago. “What I know is that only when sales recover will we see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Yau said. “But I do not know when that is coming.”