Let’s reconcile to a diet of squid as we overfish to our own peril

For the past decade, my clan village neighbours in Clear Water Bay have had panic attacks every weekend as I swim out across the bay for some leisurely exercise out in the open sea.

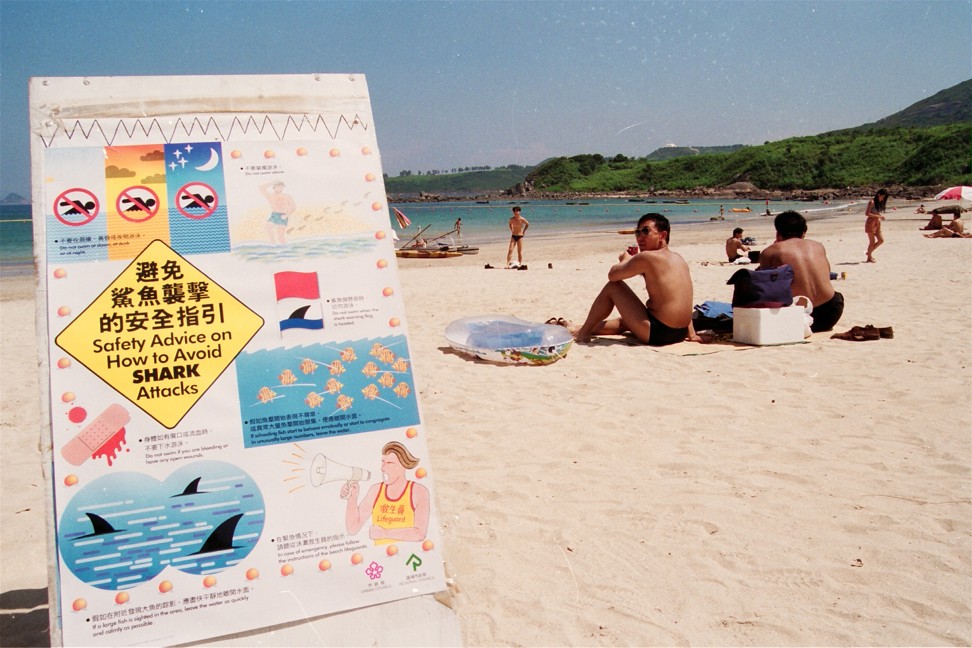

They have for 10 years warned me that I will surely be attacked and eaten by a shark. They remind me of an old-timer attacked and killed at the edge of the bay a couple of decades ago.

I ignore them and their warnings, not because of any eccentric and ill-placed bravery on my part. Rather, the sea in Shelter Bay has been so ruthlessly fished to death over the decades that underwater surveys show a huge marine desert. Why should any rational shark nowadays stray anywhere near the waters around my bay when there is so little sea life on offer? I will start to worry if and when the sea life returns.

Every evening, four or five clan villagers wade waist-deep out across the bay with brilliant torches and floating polystyrene boxes to seduce what little sealife that remains.

They return to shore with desultory catches and complain to me about how rich the catches used to be when they waded out into the bay with their grandfathers. I have tried many times to ask them why catches might have declined so. Not one of them seems willing or able to see any link with their indiscriminate nightly pillage and the disappearance of fish.

So nowadays, they rely on the daytime harvests of clams raked up from the low tide sand by their wives, and on squid – those ferocious cephalopod predators they often blame for the disappearance of fish and that are so easily bewitched by their bright waterproof lights.

Nearby, but a little further out to sea – and targeting squid on a much grander scale – are the squid boats that sit all night with their lights ablaze across the sea horizon.

The Hong Kong government may, since 2012, have imposed an effective trawling ban in Hong Kong waters, but that does not apply to small-scale fisherfolk and squid boats, which still today report catches amounting to 145,000 tonnes a year – way down from the 1989 peak of 230,000 tonnes but still enough to stall recovery of our marine environment.

In 2002, there were just 2.18 million tonnes hauled from the sea worldwide, according to the organisation’s data. By 2005, that had risen to 3.9 million tonnes, and I can find no accurate numbers since then. This is only a small proportion of the global wild fish catch, which has stayed steady at about 90 million tonnes a year for the past 20 years, but it is growing fast.

Once regarded as by-catch to be disdained and discarded, squid has become a staple for many fleets around the world.

Compared to fish, very little is known about squid and their lifestyles. But there is a dangerously naive belief that it is impossible to overfish them. Why? Because almost all squid have an astonishingly short lifespan – rarely more than two years. Like octopus and cuttlefish, they race to maturity with barely decent haste, predate ferociously on fish and other cephalopods, mate, nurture their eggs and die.

This is a diversion, but this brings to mind a beguiling new book by philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith called Other Minds – the Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life.

He intriguingly asks why creatures that live for just two years – not long enough for a human child to have begun to string intelligent sentences together – can derive any evolutionary benefit from developing such huge and sophisticated brains.

Why, too, can creatures develop such astonishingly colourful pyrotechnic signalling displays but at the same time be colour-blind? If there was ever a conundrum wrapped inside an enigma, this is surely it.

Inevitably, the average squid fisherman spares not a moment’s thought to this enigma. And similarly inevitably, a large part of the boom in demand for squid comes from China – in particular the coastal city of Zhoushan in Zhejiang, which today accounts for about 70 per cent of China’s total squid catch.

The city’s story is that of fishing communities around the world (the World Bank says 250 million people worldwide depend on fisheries for their livelihoods): before the 1970s, their fishermen ignored squid as irritating by-catch.

But as white fish stocks have declined, so they have banded together, using subsidies from the government, to build bigger deep-ocean trawlers that today can stay at sea for as long as two years, and roam as far as Argentina, increasingly target squid that are not subject to global regulation as fish are.

Furnished with a new 5.6 billion yuan (US$822.9 million) port intended to accommodate these new deep-ocean trawlers, Zhoushan aims to bring home 1 million tonnes of seafood a year by 2020 – which is double today’s catch.

“Squid can’t collapse like other species,” he said earlier this year. “We only fish the top level of the ocean. We haven’t developed the middle and lower levels yet.”

I sense the answer to Chen is “Give them time …” Surely it is only a matter of time before someone develops some means of predating on “middle and lower levels”.

Meanwhile, I find it alarming that so many – including my clan village fishermen and the families feasting in Sai Kung’s fish restaurants – are already reconciled to the gradual disappearance of the white fish that we have so long treasured, and are preparing new and interesting ways to adjust to a diet of squid.

For my part, I am assuming that if I ever do eventually get attacked outside my bay during my weekend swim, it will be by a squid, not a shark.

Not so charismatic a way to die, methinks.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view