Here’s what Xi Jinping’s new Silk Road can learn from the Marshall Plan

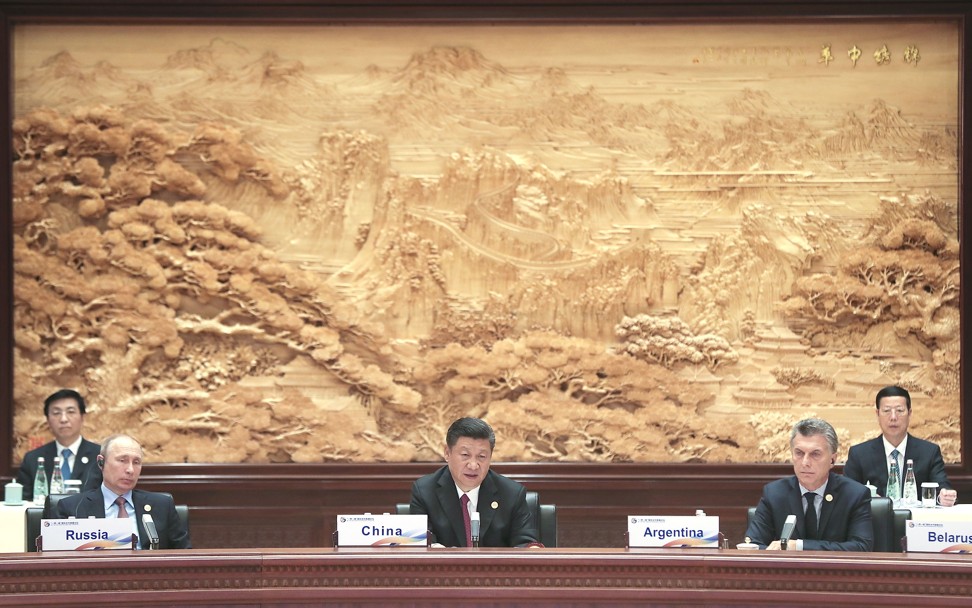

The sky over Beijing was a crisp, dark blue. With the arrival of 29 foreign leaders for the Belt and Road Summit last month, officials had made every effort to clear the air and roll out a bright red carpet. Representatives from more than 60 participating countries came to discuss China’s grand initiative: massive infrastructure investment to link China and Europe, and most countries in between, by land and sea.

The project has been under way for several years, launched by China’s President Xi Jinping in 2013. Since then, projects have sprung up across Asia and even parts of East Africa, stretching from ports in Pakistan and Sri Lanka to railways in Malaysia and Indonesia.

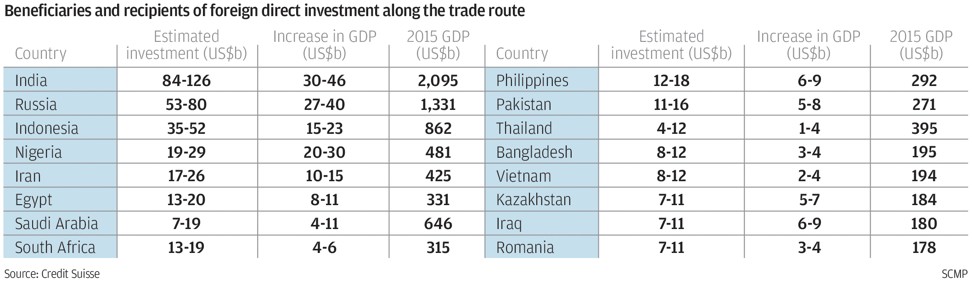

The numbers, even if a little vague, are staggering. Chinese banks have already invested about US$250 billion in participating countries in recent years, financing roads, pipelines, rail tracks, container terminals and power plants.

That is serious financial muscle. And if implemented as envisaged, it could transform the economics of the region, especially in those countries currently cut off from easy physical access to global markets.

It is no surprise therefore that the trade initiative has invited comparisons to the Marshall Plan, the US funding programme that injected life into Western Europe’s economies after the second world war. Between 1948 and 1952, the US lent out US$13 billion, or roughly US$130 billion in today’s money, to finance reconstruction and the purchase of industrial goods from the US, thereby kick-starting the continent’s post-war boom.

As Chinese officials have remarked, the initiative is not designed as a Marshall Plan for Asia. Officials, for example, reject the idea that the project serves any geopolitical goals, unlike the US-led scheme that was rolled out at the start of the cold war.

From a Chinese perspective, it is less intrusive, confined merely to the funding of infrastructure, without any intention to remodel recipient economies along a preferred model.

Still, it is instructive to look at the Marshall Plan more closely and derive lessons from its success for Beijing’s trade initiative. Three stand out.

Beijing’s trade initiative might benefit from a similar, complementary trade agreement. The risk, after all, is that vast infrastructure will be built in recipient countries without generating the kind of growth that either justifies these projects or allows them to accelerate development. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership is currently in negotiations to liberalise trade among key Asian economies. But for Beijing’s trade scheme to be a success, it needs to go further than that. For one, it does not include many of the smaller countries that will, as a share of their economy, receive the bulk of funding. In addition, the symmetric dismantling of trade barriers may not be enough: China, as the biggest economy in Asia, may need to open its doors wider, at least initially, than its partners to allow local entrepreneurship to flourish so businesses can compete with Chinese companies on a level playing field.

For example, the Bureau of Labour Statistics sent experts across the continent to study productivity and gave advice on which industries might be more suited to support economic growth.

Meanwhile, with American support, the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation, later to become the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, helped coordinate loan disbursements, pool development expertise and encourage economic integration.

Third, over time, America offered access to vast capital markets to aid Europe’s recovery. Especially in the early years, when the continent was starved of capital, funding across the Atlantic could be obtained by growing enterprises, and even budding entrepreneurs, accelerating investment. China, too, could offer a huge funding pool for companies and governments among participants in its trade scheme. Although China’s financial system is still relatively closed, preferential access could be given to issuers of bonds and equity from developing economies, raising funds on the mainland and using the proceeds locally for investment. Chinese banks are already in the process of establishing a foothold across the region, but their lending is often confined to infrastructure projects rather than entrepreneurs that will ultimately make such investments worthwhile.

The numbers are vast. And plenty of concrete will be poured in the coming years along the New Silk Road. But to make such projects a success, local economies will need to thrive and indigenous businesses grow.

China has much more to offer than construction engineers and cheap funding: opening its vast internal market for goods and capital, as well as providing expertise, would help sustain development across the region.

Frederic Neumann is HSBC’s co-head of Asia economics research