The crash of ‘97 taught us we won’t see the next one coming

‘We have had two ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ crises in the past two decades, and a third in the next couple of years cannot be ruled out’

With Hong Kong today in festive lockdown to welcome Chinese President Xi Jinping and celebrate 20 years of Chinese sovereignty, it may be important to remember that this is not the weekend’s only 20th anniversary of consequence.

And no, I am not just talking about the 20th anniversary of the publication of the first Harry Potter novel, The Philosopher’s Stone, on June 26, 1997, which must provide one of the 20th century’s epic literary landmarks.

Even more important for us in Hong Kong – though I am sure there will be some Harry Potter fans who challenge this – is the 20th anniversary tomorrow of the Tom Yum Goong crisis in Thailand, which triggered the Asian financial crisis that wrought havoc across our economies for an awful 18 months and whose scars still smart today.

As we step nervously out from a decade of quantitative easing... the dangers as asset markets adjust cannot be underestimated

I am sure there are many who wish our past 20 years could have mirrored the trajectory of J K Rowling and Harry Potter. As a struggling single mum in an Edinburgh apartment, with eight publishers’ rejection slips in her pocket, could Rowling ever have imagined that her advance of £2,500 from Bloomsbury and a meagre initial print run of 500 copies (mostly to libraries) would have grown today to a global Harry Potter publishing brand worth US$25 billion, with sales of 400 million books in 67 languages across the world? Who would have foreseen Rowling as one of the world’s richest women – and by far its richest novelist – with wealth up somewhere around US$2 billion?

But sadly, our own trajectory from the Tom Yum Goong crisis has been immensely more stressful and challenging – and perhaps goes a long way to explaining why pervasive angst prevails today, in sharp contrast with the rambunctious swaggering self-confidence that marked our 1990s bubble years.

It would be wrong to say no one saw the Asian financial crisis coming. Many economists were wringing hands over high levels of national and corporate debt, in particular debt denominated in US dollars. Many were concerned about the large trade deficits of many of Asia’s economies. But no one saw the “perfect storm” coming. Nor did they anticipate how astonishingly interconnected we all were and how many dominos would crash into each other before the storm blew itself out 18 months later.

By the time the dominos stopped falling, the economies of Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines had been savaged. Japan and the US had been buffeted powerfully. Russia and Brazil had brought the crash into distant continents. The International Monetary Fund had negotiated bailouts ranging from US$57 billion for South Korea and US$40 billion for Indonesia and Brazil to more modest billions in Thailand, Russia and Malaysia. Currencies across the region had crashed – the Indonesian rupiah to about one-fifth of its pre-crisis level. Stock markets had been shredded. It was estimated that 80 million Indonesians fell below the poverty line during the crisis. Leaders inevitably paid the price. Suharto was unseated in Indonesia after 32 years in office. In South Korea, the opposition Democratic party swept to power under Kim Dae-jung for the first time in the country’s post-war history. The scene was set in Thailand for a series of military coups.

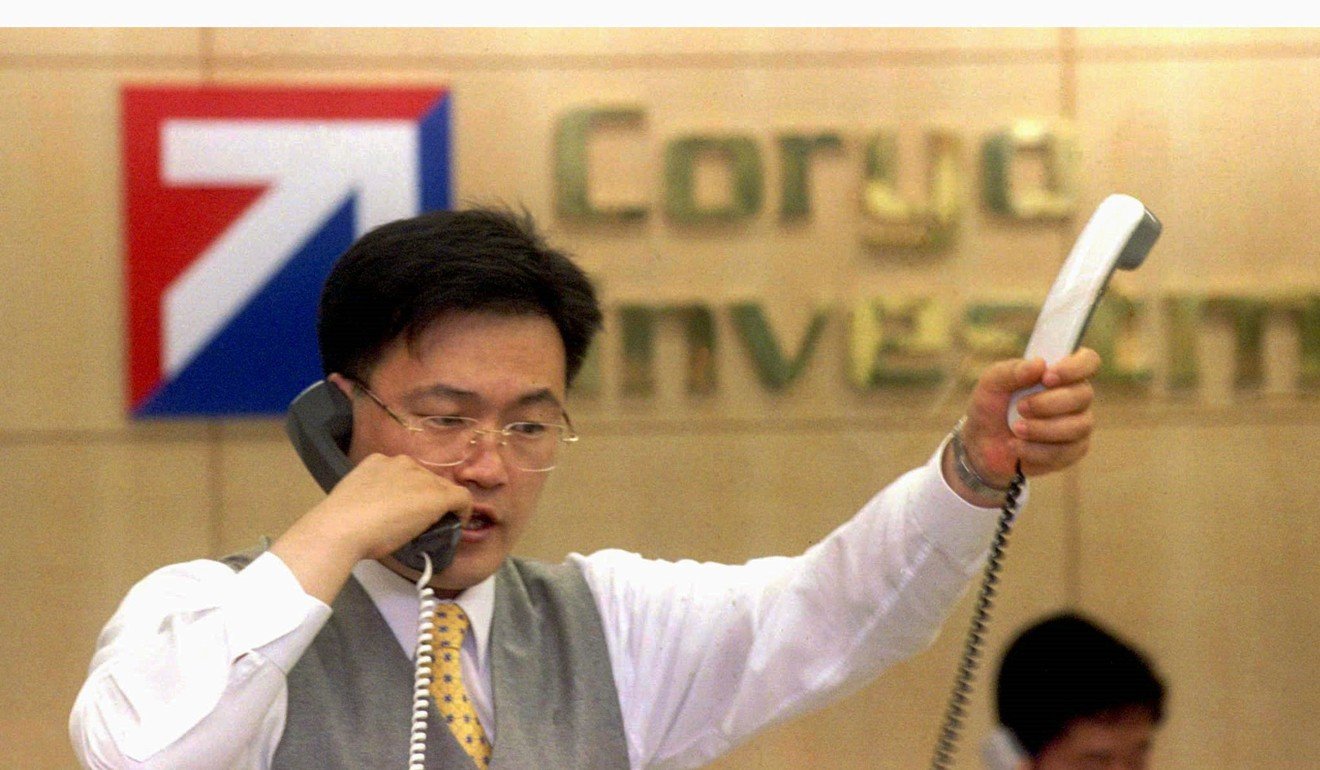

I recall as we prepared in Hong Kong to host the September World Bank/IMF meeting in the then newly minted Convention Centre, a sense of complacent superiority prevailing among Hong Kong’s financial community. The supine view was that Hong Kong’s financial institutions were well capitalised and tightly regulated, that Hong Kong companies carried little debt and that the crises erupting in the region around us could not possibly happen here.

What a shock it was, barely a month later, to watch the “Black Monday” stock market crash wipe US$2.9 billion off Hong Kong’s stock market capitalisation and the Hong Kong dollar peg to the greenback come under ruthless assault from a number of powerful US predators. Even more of a shock was to see property values crash to 30 per cent of 1997 values. The sobering lesson was that Hong Kong, with no local market of consequence, was an economy that depended on flows – and when the flows dried up as the crisis deepened, so Hong Kong rapidly joined the wounded.

Our economy contracted 5.5 per cent in 1998, and we plunged into six successive years of deflation – only to have the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic knock us firmly backwards again in 2003, and the global recession to cut our knees off in 2008. In short, 20 challenging years, and none of it the fault of Beijing.

In 1998, looking back over the carnage of the previous year, Joseph Yam Chi-kwong, then head of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, commented soberly that “the severity of the Asian crisis is a once-in-a-lifetime event and no banking system in the region can hope to be unaffected by it”. That was perhaps wise with the benefit of 20:20 hindsight, but I wonder how sobered he was to see a second “once-in-a-lifetime” event engulf us all in 2008.

So what are the lessons of these three highly contrasted 20th anniversaries? The first must surely be that crises can come from the most unexpected directions: at exactly the moment when many in Hong Kong were battening down and predicting meddlesome harm from our North, the real tsunami swept in from the “Tom Yum Goong” crisis from the south.

The second lesson must surely be how remarkably interconnected we all are. Within months of the Thai baht devaluation on July 2, 1997, the tsunami had wrought damage across South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, the US, Brazil and Russia. US President Donald Trump please take note: however determined you are to think only and always of “America first”, the brutal reality is that we are all in this together. Accidents or missteps in the US can harm us grievously here across the Pacific, but so, too, can accidents or missteps in Asia or the Middle East or Europe deeply harm the US.

As we step nervously out from a decade of quantitative easing and extraordinary economy-distorting low interest rates, so the dangers as asset markets adjust cannot be underestimated. We have had two “once-in-a-lifetime” crises in the past two decades, and a third in the next couple of years cannot be ruled out. All we can be sure of is that it will not come from the direction we are expecting.

But the final Rowling lesson might be more cheering: just when you feel most hopelessly down and out, miraculous things can still happen – with or without Harry Potter’s wizardry. Hong Kong retains ferocious competitive strengths, and alongside one of the world’s largest and most dynamic economies is well placed to thrive. We don’t need Xi to remind us of that today, but he almost certainly will.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view