The flimsy excuses of governments when they’re caught unprepared at moments of woe

Governments in Tokyo, Taipei and Singapore – as well as Hong Kong – have done what any moderately wealthy city should do, and built protective infrastructure to minimise threats from natural disasters that can in general terms be well anticipated.

Over the past week, most of the world seems to have been under water. Storms claimed to be the worst in 50 years have wrought havoc, death and disruption in Texas, Mumbai, Bihar, Nepal, Bangladesh – and of course here in Hong Kong and Macau.

Before the cost to these economies – both economic and in terms of death, injury and dislocation – has even been estimated, governments wrestling to deal with and recover from these disasters have worked overtime to explain the shocking rarity of such superstorms, “black swan” events all, and the impossibility of anticipating them or containing their impact.

But of course, they are not “black swan” events. Such “once every hundred years” storms seem now to be occurring most decades, and are likely to be even more frequent as global warming gathers momentum over decades to come. Their impacts can be anticipated. Protections to minimise the tragic human and economic harm are possible. As Bloomberg Businessweek commented last week: “Houston has been wet since birth.”

As emergency Federal aid begins to be dished out, many families around Houston and the Gulf Coast will be receiving funds for the third time in a decade to rebuild their lives. As Businessweek noted: “Over the past decade, the Federal government spent more than US$350 billion on disaster recovery. Much of the money has gone to homes that keep getting damaged; 1.3 million households have applied for federal disaster assistance money at least twice since 1998—many of them in the same areas hit hardest by Harvey. Repeat claims are also common.”

The sad and cynical reality is that actuarial advice says it is cheaper to rebuild lives after catastrophic storms have struck, than it is to build infrastructure that will avert or at least mitigate such catastrophes; even when the cost of storm like Harvey may inflict damages of more than US$120 billion, and global supplies of oil, gas and petroleum are massively disrupted.

Of course, desperately poor countries like Bangladesh, India, and even parts of China, are not so well placed. It is a grisly reality that for decades to come, such countries will suffer storm-related catastrophes with little power to prevent massive loss of life and livelihood.

Was anyone surprised to learn that the government had, in 2012, created a Council for the Treatment of Unforeseen Incidents after recent massive storm damage? Was anyone surprised to learn that the Council has met only sporadically, and implemented virtually nothing?

Should anyone be comforted by Chief Executive Fernando Chui Sai-on’s grovelling apologies, and creation of a new inquiry body, this time called the Commission for Reviewing and Monitoring the Improvements of the Response Mechanism to Major Disasters?

Should anyone be surprised by concerns that meteorological officials may have delayed raising appropriate storm warnings because of the financial impact of closing casinos?

Surely the dismissal of Fong Soi-kun, the head of Macau’s Meteorological and Geophysical Bureau, reeks of scapegoating?

The truth is that the Macau government and the casino barons that run Macau – and of course the US administration bending to lobbying for a “light hand” by the oil industry concentrated around Houston and the Gulf Coast – have only the flimsiest excuses for failing adequately to fund the cost of protecting lives and livelihoods during typhoons, hurricanes, and other entirely predictable natural disasters.

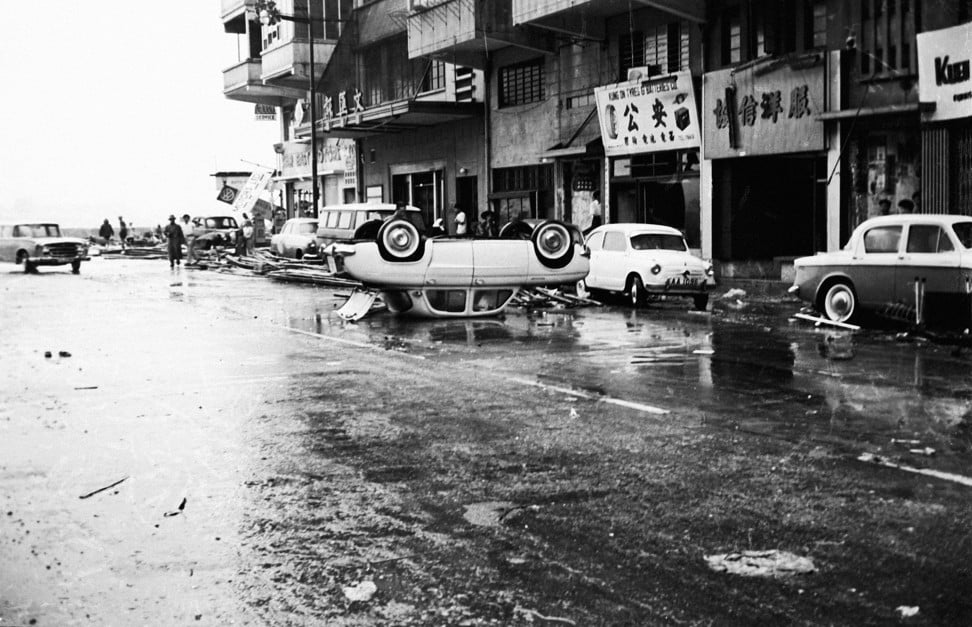

Hong Kong has performed more creditably over recent decades, after its own share of catastrophes in the early decades of the last century: unnamed typhoons in 1906 and 1937 caused 15,000 and 11,000 deaths respectively – the first of these particularly awful since Hong Kong’s population then was just 320,000.

But after the massive 260-km per hour Typhoon Wanda wrecked Hong Kong in 1962, and black rains triggered landslides that destroyed Po Shan Terrace above Happy Valley in 1972 (John Le Carre’s novel The Honourable Schoolboy was built around that disaster in which 148 people died), more meaningful pre-emptive action was taken.

After three decades of work, the Buildings Department in 1983 published the first Code of Practice on Wind Effects in Hong Kong to make sure the city’s buildings were sturdy enough to cope with the worst of typhoons. And in 1996, after a similarly long period of study, work began on massive floodwater tunnels underneath Hong Kong island.

Governments in Tokyo, Taipei and Singapore – as well as Hong Kong – have done what any moderately wealthy city should do, and built protective infrastructure to minimise threats from natural disasters that can in general terms be well anticipated.

The gold standard for such action is surely set by the Netherlands – a country in which over 90 per cent of its population live in homes that are many metres below sea level, and which remain habitable only because of massive long-term investment in seawalls, dams, dikes, sluices, pumps and docks.

It is noteworthy that the Dutch government, much concerned by the likelihood that sea levels will over the next 80 years rise around 2 metres, have set about a wholly new round of infrastructure investment. Astonishingly, this may involve lifting the entire country by up to 10 metres by drawing 22.3 billion cubic metres of sand from the North Sea. The cost is likely to be immense. But they calculate the cost of neglect will be even more immense. As one commentator noted: “When the Dutch have doubts about water, it’s time to worry.”

Of course, in the US, Donald Trump still insists that global warming is a hoax. But as a Businessweek columnist wryly noted: “If climate change is a hoax, as President Trump has said, then Houstonians just got 50 inches of hoax dumped on their soaking wet heads.”

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view.