Future still in doubt for Hong Kong’s ‘quirky’ small-cap exchange, the GEM

‘Not many investors want to trade here. In contrast, it has attracted a lot of speculators. So the result is even fewer companies have wanted to list here’

Hong Kong’s Growth Enterprise Market (GEM) was created 18 years ago with high hopes of changing the lives and fortunes of young Asian technology companies.

Today, the GEM, rather than being the region’s very own Nasdaq, has become home to many quirky things, including the world’s wildest price swings, with only a small percentage of its component companies’ shares actually available to the public to trade.

“Practically, the GEM has failed in its original mission to become a thriving Nasdaq-style stock exchange,” said Vincent Chan, head of China research for Credit Suisse.

“Not many investors want to trade here. In contrast, it has attracted a lot of speculators. So the result is even fewer companies have wanted to list here.”

Set up by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange [now Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing, or HKEX], officials had high aspirations the GEM would become a magnate for Asian technology startups, a place where emerging companies without proven track records could finance growth, and venture capitalists could achieve successful exits from their investments. That plan, however, hasn’t quite worked out that way.

Practically, the GEM has failed in its original mission to become a thriving Nasdaq-style stock exchange

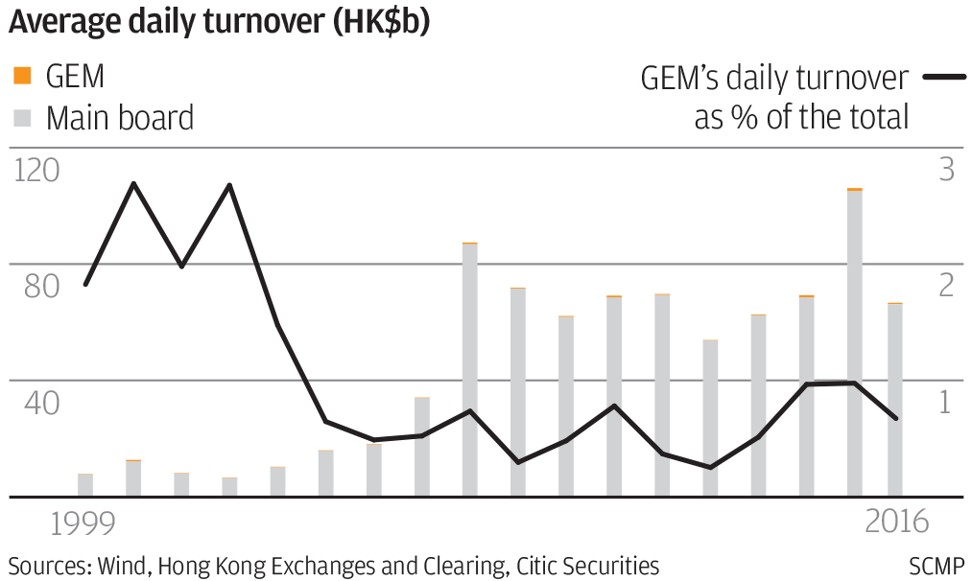

In May 2017, average daily turnover for the GEM was HK$742 million, under 1 per cent of the main board’s daily average for the same months – that’s even lower than when it was launched with great fanfare in November 1999

Back then, its average daily turnover was HK$144 million, but that was 2 per cent of the main board’s HK$7.8 billion. The percentage ratio went on to hit its peaks in 2000 and 2002, respectively, as the dot-com bubble in 2000 and China’s rapid economic growth in 2002 sparked greater investor interest, especially in start-ups.

In both years, the GEM’s average daily turnover made up 2.7 per cent of the main board’s amount.

“It is not functioning as intended.”

On June 15, for instance, among its 281 component companies, 215 traded at a price less than HK$1 per share. 35 stocks had no transactions at all, while 12 had a daily turnover below HK$10,000. Only 12 companies had a daily turnover above HK$10 million.

A quiet marketplace by anyone’s standing, and one in a sustained decline since 2002.

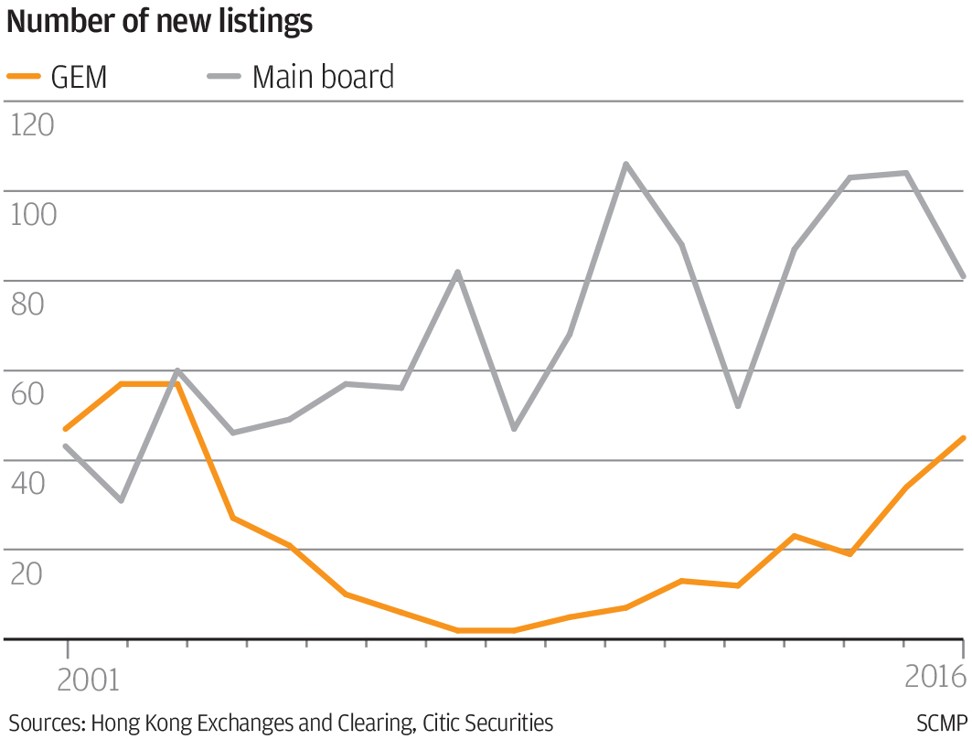

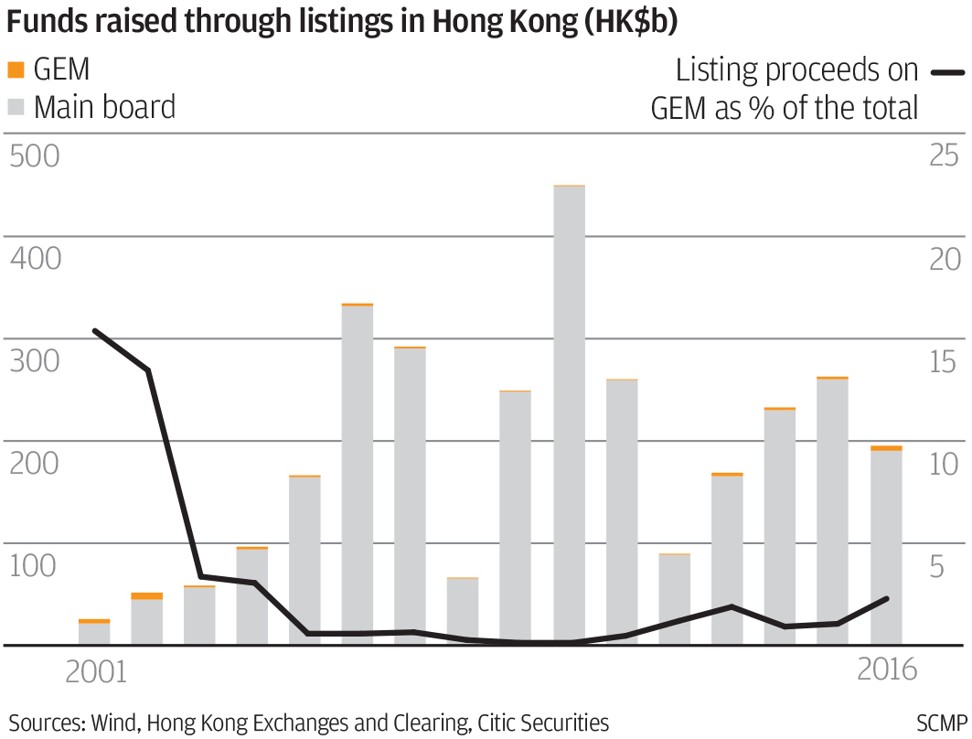

In 2002, 57 initial public offerings (IPO) on the GEM raised a total HK$7 billion, accounting for nearly 14 per cent of Hong Kong’s total IPO fund-raising amount during the year.

In 2015, only 34 companies went public on the board, raising HK$2.7 billion, making up 1 per cent of the city’s total funds raised through IPOs. In 2016, the percentage ratio stayed low at 2.3 per cent.

Nonetheless, the heady levels of early 2000 seemed a long way away.

“It’s been a vicious spiral,” added Hu from Citic Securities, adding that sluggish trading has affected the pricing of the equities, making it even less attractive for growth companies to raise capital here through equity financing.

But what have been the root causes of the board steady decline?

“The fundamental issue is that the there are not enough quality firms, especially not enough from the local economy,” said Credit Suisse’ Chan.

“Hong Kong hasn’t cultivated a successful tech startup culture. Without the support from the real economy, the GEM can’t thrive.”

“Good companies are the back bone of a successful securities market. ”

The timing of the GEM’s establishment was also “unfortunate”, as the dot.com bubble burst in March 2000, only months after its birth. By the end of 2002, the board’s stock index had plunged 90 per cent

Trading volumes and market value also shrank sharply, prompting some big firms to leave the lesser board for the main board, including mobile internet company Tom Online and software developer Kingdee Software.

“The original intention was good when they designed the policy to help startups succeed. But some clauses were too flexible. No one knew the real implications until years later,” said Ronald Wan, chief executive of Partner Capital Group.

One GEM rule, particularly, is regarded as being its Achilles’ heel.

Companies can list on GEM via a placement with a minimum 100 shareholders rather than a full offering to the general public. Many investors consider that as simply creating a loophole that allows a limited number of shareholders to hold large shares, thus the percentage of shares available to trade in the public is low.

In these cases, a stock price could fluctuate substantially even with a small number of shares traded, which could give large shareholders stronger power to orchestrate the price.

This concentrated structure also makes it easy for the controlling shareholders to sell the company as a shell.

Since its listings can be transferred to the main board without the scrutiny of another IPO, many companies find it easier and quicker to buy a GEM shell company to gain a full listing, the much publicised, some suggest infamous, “back door listing”.

“Demand for shell companies is particularly high among mainland Chinese companies, as they usually face a long queue to list in the mainland stock market,” Wan said.

Currently, a GEM shell could sell for around HK$350 million plus the company’s asset value. A main board shell can sell for up to HK$700 million, more than doubled the price in 1997.

Carlson Tong, chairman of the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), repeatedly expressed his concerns in 2015 and 2016 over the increasingly number of shell businesses listed in the Hong Kong’s market.

In January 2017, the SFC and the HKEX issued an unusual joint warning against the “concentrated shareholding ownership” and “unusual price volatility” of GEM listings and said they were investigating a number of deals that had caught their attention.

“The volatile price swings on the GEM have made people wonder if the Hong Kong stock market has become a Disneyland for speculators,” said Christopher Cheung Wah-fung, a lawmaker representing the financial services constituency in the Legislative Council.

“These ‘quirky’ or ‘cheating’ stocks have severely damaged Hong Kong’s reputation as an international financial hub.” Fluctuations were wild, in some cases.

In 2015, first-day share gains on the GEM averaged 740 per cent, according to the SFC. Nonetheless, within a month, the shares plunged an average 47 per cent from their peaks.

In 2016, 18 of the world’s 20 biggest IPO share surges took place on Hong Kong’s GEM.

In January 2017, OOH Holdings – an out-of-home advertising space provider in Hong Kong – spiked 28 times on its trading debut, before plunging 97 per cent from its peak within a week, stunning many market watchers.

In an attempt to address the problem and boost Hong Kong’s appeal to technology listings, HKEX launched, on June 16, long-awaited proposals to tighten listing rules and establish a brand-new trading board for young firms, the New Board, often referred to by many as the “Third Board”.

According to its plan, companies listing on GEM must issue at least 10 per cent of their IPO shares to the public. The bar will be raised for GEM listings in regard to the minimum market capitalisation and cash flow requirements.

Transfers of GEM listings to the main board will face tougher scrutiny too, while poor-performing companies will be removed from GEM more quickly than in the past.

Most importantly, the New Board will exclusively list new economy companies, such as internet startups and biotech firms.

It ill consist of two segments for startups and established companies, separately, with the startup stock segment only open to professional investors. Both segments would allow special voting rights and impose no restrictions for second listings of mainland Chinese companies.

“We want to learn from GEM’s lessons and experiences, ” said Charles Li, HKEX’s chief executive.

“The original mechanism had contradictory policy designs. We want to protect retail investors, but we also want to help companies raise funding more easily,” Li said.

“The GEM board is open to retail investors, but new listings don’t have to issue IPO shares to them. This is the worst combination.”

That’s why the exchange plans to tighten the GEM IPO rules and set up two separate segments on the New Board, Li said.