Where do blockbuster IPOs stand as the fizz goes out of Hong Kong’s stock trading debuts?

Disappointing performances by big name listings have led to questions about overpricing and excessively large fundraising targets

On the eve of what could possibly be the world’s biggest initial public offering this year, has the fizz gone out of Hong Kong’s market?

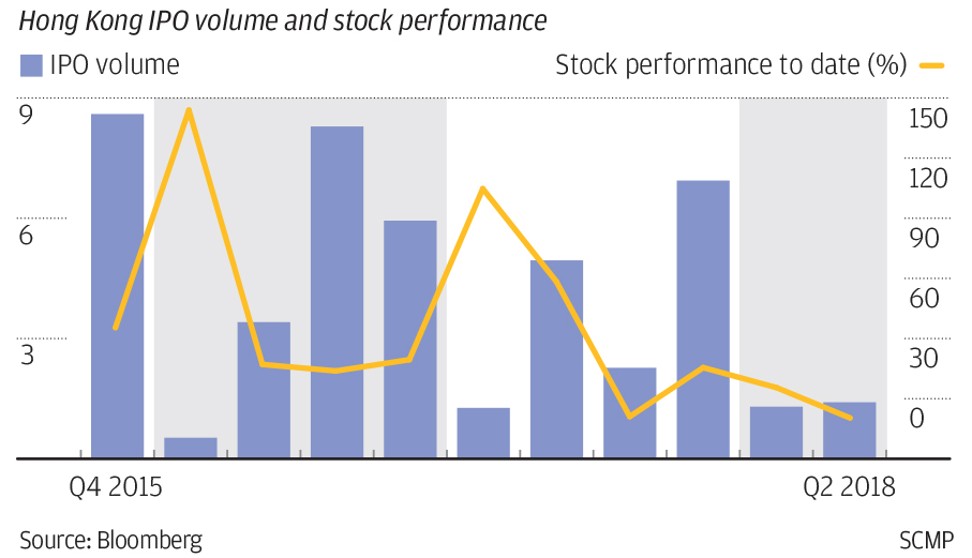

Of the 87 companies that raised funds in the city this year, 53 per cent of the total traded at prices below their offering prices in their first month of trading, according to Bloomberg data. And 20 companies fell below their offering prices on their trading debut.

Investors need to be careful, as it’s unclear if all these listings can be digested by the market and receive a positive response

These also included high-profile technology stocks, the very group of new-economy darlings that exchange officials were so convinced would be the future of the bourse that they overhauled the listing rules to accommodate them.

Overpricing and excessively large fundraising targets are some of the headwinds investors appear to be facing in Hong Kong, especially as many technology and biotechnology companies that go public are still making losses.

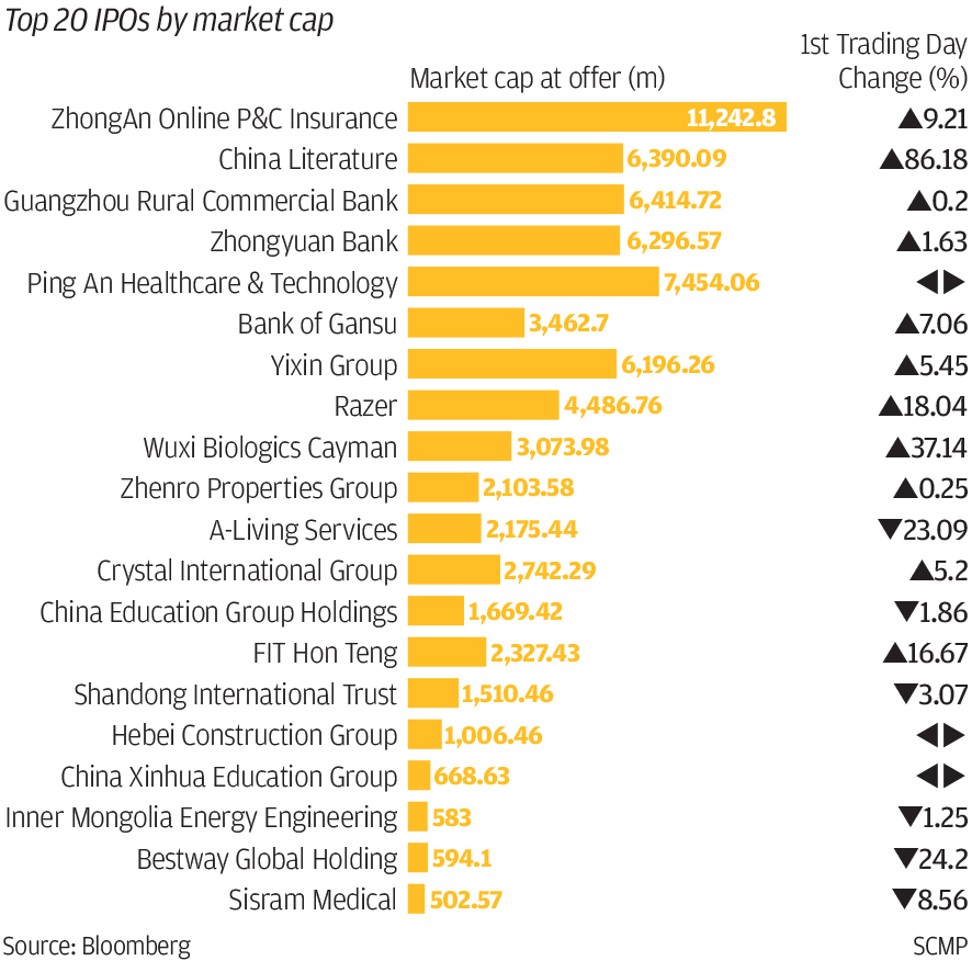

ZhongAn Online Property & Casualty Insurance, the city’s largest technology IPO of 2017, was overbought by 391 times and it’s shares soared by as much as 57 per cent within six days of its debut. But it is now trading 17 per cent below its IPO price. Similarly, Yixin Group is trading 50 per cent down from its IPO price, Razer is down 41 per cent and Ping An Healthcare and Technology, also known as Good Doctor, is down by 21 per cent.

In this climate, how Xiaomi’s US$10 billion IPO – expected next month – fares could determine how attractive Hong Kong’s newly overhauled equity market might seem to other Chinese unicorns considering large valuations and fundraising. The company is the world’s fourth-largest smartphone maker, and a lot will be riding on the success of its listing.

Moreover, what does a disappointing performance by past IPOs mean for the city’s biggest listing reform in 25 years? In April, the Hong Kong stock exchange began allowing flotations by companies with dual-class shareholding structures and new economy firms from the biotechnology sector that do not have revenue yet.

The city is gearing up for a pipeline of blockbuster IPOs this year that could amount to about US$40 billion in total, according to some estimates.

“If a stock drops significantly after its IPO, people will ask where the supporting [price] point is,” said Kevin Leung, executive director of investment strategy at Haitong International Securities. “But it is hard to know as this is a whole new business category, with no comparables.”

Underwriting banks and IPO sponsors, for a fee ranging between 3 and 6 per cent of the value of the deal, aim to set reasonable expectations ahead of time and advocate for the well-known “opening day pop” by pricing IPOs at a modest discount to allow about 20 per cent upside on market debut, as an incentive for active trading thereafter.

First day trading is often very different from long-term investment performance, as flipping and reselling a hot IPO stock in the first few days to earn a quick profit has increasingly become a practice. Stocks might also often record a downturn with the expiration of their six-month lock-in period, during which pre-IPO investors are prohibited from selling their shares.

But when IPOs end up selling below their offering prices within a year, after soaring in the first day or week of trading, then this could be an important indicator of demand being weaker than expected, and could imply that the actual price should have been lower. And if a stock does not record even an opening day pop, this could act as a stronger signal for the relative values of similar companies.

Hong Kong’s dual-class listing rules require that companies have a market capitalisation of at least HK$40 billion at listing, or have a market capitalisation of at least HK$10 billion at listing and revenue of at least HK$1 billion in their most recently audited financial year.

This means most companies are likely to be big enough to be included in benchmark indexes soon after their flotation, allowing increased flows to support the stock, analysts said.

And Chinese unicorns considering going public this year seem to be bigger, better-known household names than the ones last year: Lu.com, the online and mobile financial services platform; the ride-sharing giant Didi; Meituan-Dianping, a big provider of on-demand online services; Ant Financial Services Group, the operator of China’s biggest online payment platform; and financial technology unicorn WeLab.

But scepticism persists: did the projected growth at ZhongAn, Yixin, Razer and Good Doctor justify their high market caps? All four companies are underperforming.

Trade tensions between the United States and China, as well as expected interest rate increases by the US Federal Reserve are also weighing on market conditions this year, and have triggered fears that money may be sucked out of Asia and into the US.

“Investors need to be careful, as it’s unclear if all these listings can be digested by the market and receive a positive response. Valuations have been aggressive,” said Alvin Cheung Chi-wai, associate director at Prudential Brokerage.

Rohit Kulkarni, managing director at SharesPost Research, said Xiaomi’s reported gross margin of 13 per cent for 2017 was about three times lower than Apple’s 38 per cent, and four times lower than Samsung’s 47 per cent.

The company has performed well in India and needs to replicate this success in Brazil, Indonesia and other developing countries, said Kulkarni.

It is rumoured that Xiaomi has persuaded institutional investors in the US and Europe to value its business at no less than US$70 billion, falling back from the US$100 billion initially expected. Based on its 2017 adjusted net profit of about 5.4 billion yuan (US$841 million), this would give the Beijing-based company a price to earnings ratio of 80 to 120 times, well above Apple’s 18 times.

Edward Au, co-leader of the National Public Offering Group at Deloitte China, said the maturity of Hong Kong’s stock market – because of its large investor base made up of institutional investors – meant it was able to better price an IPO to meet demand. In 2016, 77 per cent of Hong Kong’s securities trading was made up of exchange participants and institutional investors, with the remaining 23 per cent coming from retail investors, according to a survey by bourse operator Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing.

But Au said he still expected the Hong Kong IPO market to shrink this year, mainly driven by listings of small and medium-sized companies and biotechnology firms, compared with jumbo listings by Chinese financial institutions in the past.

He forecast the market to continue slipping to about US$20-24 billion in 2018, compared with US$35 billion in 2017, which itself was the smallest amount since the financial crisis in 2008.