Now that China’s securities watchdog has grown its regulatory teeth, how hard can it bite?

Until July’s vaccine scandal, China had no provision for expelling polluters or even makers of toxic foodstuff from the stock market. The annual delisting ratio was 0.2 per cent since 2001, well below 10 per cent in the US

China’s worst public heath crisis in a decade, brought on by substandard and expired vaccines flowing into the market, prompted a swift and harsh crackdown last month by the government.

Errant executives at the producer have been arrested, with billions of yuan wiped off the company’s value, after instructions by President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang to get to the bottom of the scandal that has shaken public confidence and caused widespread public anger.

Reinforcing the government’s crackdown, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) published rules last week that laid the legal groundwork for expelling companies that harmed public health, or whose actions endangered national and ecological security.

In the regulator’s cross hair is Changsheng Bio-technology, which was exposed last month to have falsified production and inspection data for a rabies vaccine, as well as selling substandard vaccines to infants. A dozen of the company’s executives are under arrest, while the stock has lost two-thirds of its value since July 16.

“Changsheng is unlikely to be the last such incident, but China can reduce the frequency of such scandals in the future by fostering a business culture that prioritises the rule of law,” said Brock Silvers, managing director at Kaiyuan Capital, a private equity investment firm in Shanghai. “Until that time, it can merely make examples of the most egregious offenders.”

China’s stock market, which was just surpassed in capitalisation by Japan amid the Sino-US trade war, is also one of Asia’s most tightly regulated bourses, with thousands of lines of regulations on everything from disclosure to stock price gyrations.

Until Changsheng’s scandal last month, China’s securities regulatory framework had no provision for kicking out polluters or even makers of toxic foodstuff and hazardous products.

Nearly 60 companies have been kicked off the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges since the 2001 expulsion of Shanghai Narcissus Electric Appliances, chalking up an annual delisting ratio of less than 0.2 per cent, well below the 10 per cent average in the US, according to calculations by the South China Morning Post.

Every single one of those 60 companies expelled breached financial rules: either for fraud and disclosure breaches in their financial statements or initial offering prospectus, or for three consecutive years of losses.

Crimes such as polluting the environment, breaches of food safety or labour regulations, and even monopolistic pricing were treated with slaps on the wrist, a reprimand or a financial penalty at worst. As many as 115 companies had been reprimanded for such breaches in the past five years on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, paying a total fine of 323.3 million yuan (US$47 million), according to data compiled by the Post.

China’s stocks regulator sets legal framework to expel firms that pollute, or make fake vaccines

Moreover, China has been mainly fining companies that breach rules on illegal sea reclamation, illegal land use, price monopoly and waste water treatment in the past five years. Only about 5 per cent of the of fines, or 16.9 million yuan, were for unqualified and low-quality drugs and medicine, stock filings data showed.

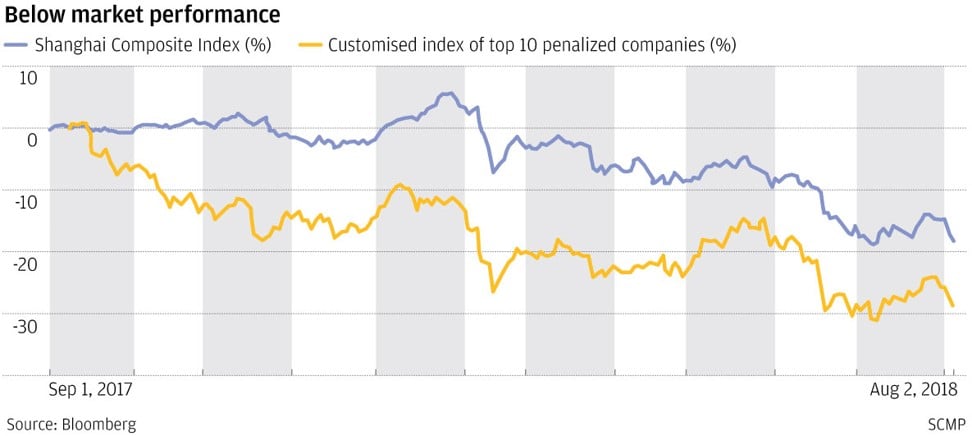

To be sure, companies that have been reprimanded or fined get the cold shoulder from both institutional funds and retail investors, at least temporarily. Stock prices fell by about 7 per cent on average among the companies paying the 10 biggest fines, in the first three months after their penalties, Bloomberg data showed. Their stocks also lagged the Shanghai Composite Index by about half in the past 11 months.

But Chinese investors have short memories, and are a forgiving lot. Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group, one of China’s largest dairy producers caught up in a 2008 scandal that tainted the entire industry, has seen its shares soaring by 950 per cent over a decade.

At the 2008 scandal was Sanlu Group, one of China’s oldest dairy producers. The Hebei-based company was caught adding melamine to its infant formula to bolster its protein content, a practice that ultimately killed six babies and sickened 300,000. The unlisted company was forced into bankruptcy, its assets stripped and sold, while its executives were jailed.

The scandal tainted 22 other dairy producers by association, in an industry wide scandal that took years to recover. To this day, a cottage industry exists where travellers courier cans of milk powder from Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand back to Chinese households.

Still, Yili recovered after initially falling by 34 per cent when the scandal first broke. By the time the company was caught in a second scandal in 2010 that involved mercury-tainted milk, its stock was up by 150 per cent.

Mengniu Dairy Group fell by as much as 46 per cent in 2008, and subsequently reversed into a gain of over 200 per cent by today. Bright Dairy dropped about 38 per cent in 2008 before paring losses, trading back up about 23 per cent.

Similarly Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development – which bought pigs that were fed an illegal additive to induce the growth of lean meat in 2011- dived over 30 per cent over a period of a month, but has erased all the losses today.

Sun Xianze, who oversaw food safety regulations in the food and drug administration, received a demerit, the lightest of all penalties given to the responsible group of cadres. Six years after the scandal, Sun was assigned to oversee drug safety in the same government agency until his retirement in March. It was during Sun’s tenure that the latest vaccine scandal has broken out.

Other officials to make a comeback include Wu Xianguo, the commissar of Shijiazhuang, the epicentre of the Sanlu scandal. Five years after he was fired during the scandal, Wu was back in public office, albeit with a lower rank overseeing rural affairs in the provincial government.

“Stock exchanges should request the delisting and termination of trading of listed shares in strict accordance to law of companies whose activities severely harm national security, public safety, ecological safety, public health safety, or the public interest,” the China Securities and Regulatory Commission (CSRC) said in a statement.

As nationwide calls to hold government officials and businesspeople accountable continued to mount in the past week, Changsheng shares plunged about 63 per cent. Beijing has also ordered the arrest of 18 people from the firm and the Shenzhen bourse has already barred its major shareholders and executives from selling the stock. Repeated calls and an email seeking for comment from Changsheng board secretary went unanswered.

Clarification of delisting rules and continuous revisions of stock guidelines were important steps needed to expose hidden scandals, improve transparency, and reduce the likelihood of such scandals in the future, analysts said.

An expulsion of Changsheng would deny it access to fundraising, often a major concern for Chinese companies, and could be used as a precedent for other cases, they said.

Now that the Chinese watchdog has been given regulatory teeth, how hard will it bite?

The new rules could even be made retroactive, which allowed for companies that had previously been penalised or reprimanded to be expelled if they have not cleaned up their act, said Cai Yongmei, a partner at Simmons & Simmons law firm in Beijing.

“Unless relevant companies have been delisted under the old rules, any company which has been subject to suspension or delisting before July 27 would be liable top expulsion under the new rules,” Cai said.

Chongqing Brewery, which was fined 24.9 million yuan in 2014 for breaching environmental regulations on waste treatment, said it’s not in any danger of being kicked off the Shanghai Stock Exchange, where its shares are traded. The company is already implementing the sustainable development strategy and waste-treatment standards of its controlling shareholder Carlsberg Group since the Danish company’s 2013 investment, said a brewery official who declined to identify himself.

The same goes for Inner Mongolia Eerduosi Resources, which controls the world’s largest producer of cashmere apparel products. Eerduosi was fined 19.37 million yuan last year for monopolistic pricing on its luxury fabric.

The new (delisting) scheme is aimed at major violations with a widespread social impact, so it should be mainly targeted at Changsheng, said an Eerduosi spokesperson. Listed companies with normal operations, which have already paid their dues are unlikely to be affected, she said.

The entire exercise would be akin to “killing the chickens to scare the monkeys,” said Kaiyuan’s Silvers, invoking a Chinese proverb about making an example of others.