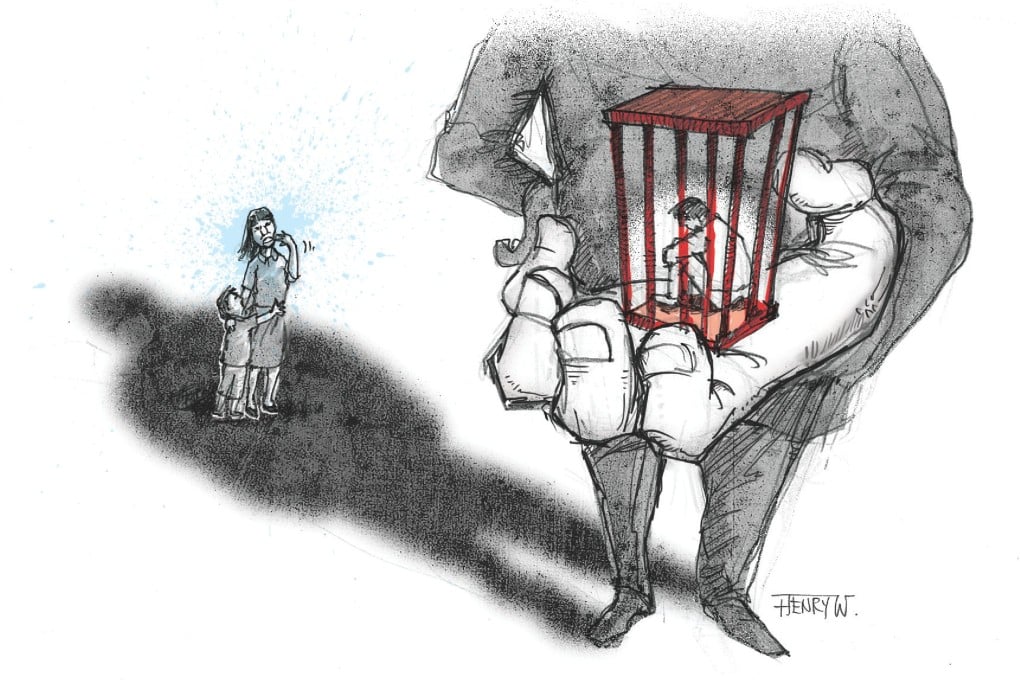

Beijing plays on people’s fear to stop dissent as June 4 nears

Chang Ping says Beijing not only has set out to silence its critics as June 4 nears, but it tries to keep things quiet by exploiting other people's worry for the detainees' safety

In the run-up to the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests, the Chinese government has gone on the offensive. Citing various absurd reasons, it has detained a large number of people who have either criticised the government in the past or whom authorities believe may do so. They include the respected human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang , retired academic Xu Youyu and political activist Hu Shigen .

Their arrests have sparked international concern. Many from around the world - from international organisations and well-known academics to ordinary people - have raised their voice in protest.

By contrast, the detainees' family members have largely kept quiet and avoided talking to the media. Some of them might simply not want to be in the news, but their bigger worry is angering the government; by speaking out, they fear they will provoke harsher treatment of their loved ones in retaliation.

Some family members were directly warned by the government not to accept interview requests from foreign media (the local media would not dare to interview them), and not to express their views on the internet. Their phones are likely to have been bugged, and secret police shadow them wherever they go.

I understand their difficulties. They know well that their loved ones did not break the law, but were jailed for speaking out on sensitive issues or for challenging the authority of the government. In China then as now, an emperor's displeasure is cause for arresting someone; his rage is reason enough to punish that person.

I'm reminded of a heated argument I witnessed in Chengdu in 2010. Activist Tan Zuoren had just been sentenced to five years in jail for "inciting subversion of state power" after he exposed the shoddy construction of school buildings that collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and published an online article on the June 4 movement.

A woman who claimed to be a good friend of Tan's laid into his lawyer, Pu Zhiqiang, for contributing to his heavy sentence by accepting foreign media interviews despite a government warning not to do so, for the selfish reason of boosting Pu's own profile. She also blamed Pu for angering the Sichuan authorities by taking part in the production of dissident artist Ai Weiwei's film, Disturbing the Peace (or Laoma Tihua in Chinese), which documented police abuse there.