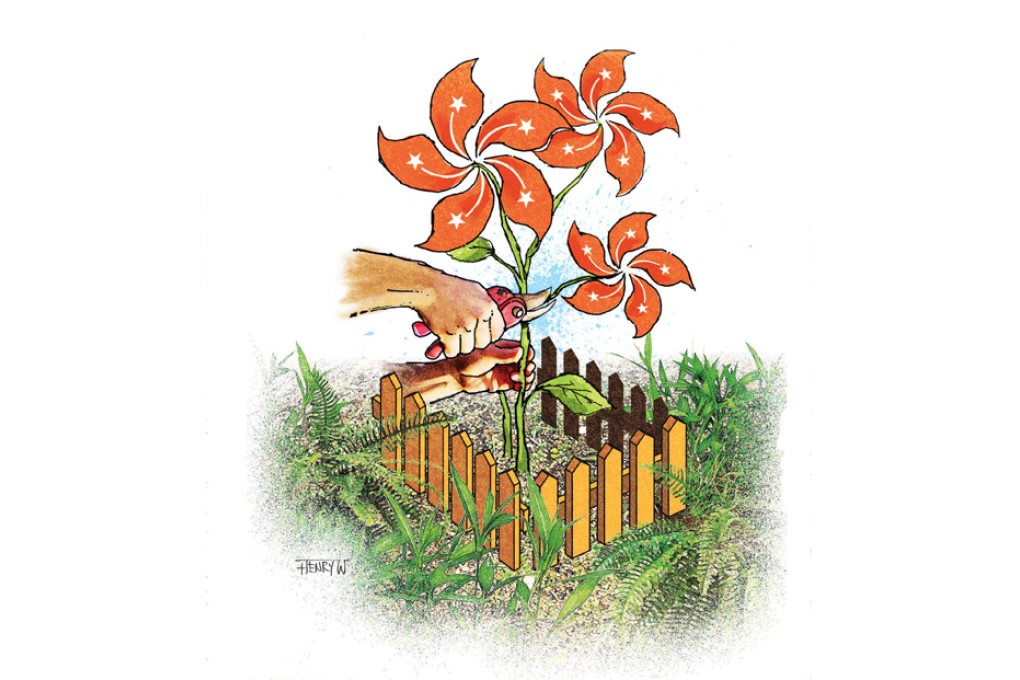

Once again, Beijing turns its back on the people of Hong Kong

Keane Shum says Beijing's betrayal of its pledge of universal suffrage may be just one more time Hong Kong has been asked to take one for the good of the nation, but it nonetheless stings

I once thought I would never say goodbye to Hong Kong. Or, that if I ever did, it would be by my own choice. I should have known better. In this city, the choice has never been ours.

We are used to this. Coteries of old men - and three extraordinary women - in faraway places have been signing away our rights for 172 years. No one on that ship in Nanjing ever thought to ask how the people on this barren rock felt about being ransomed for opium.

No one in Beijing negotiating the terms of the lease on the New Territories considered bringing its occupants to the table.

No one at the table in suite 336 of The Peninsula on Christmas Day, 1941, was even Chinese.

And nowhere in the declaration Deng Xiaoping and Margaret Thatcher toasted 30 years ago is there any reference to the people of Hong Kong.

We are used to this, and maybe like we have before, we will soldier on, even on a battlefield where it sometimes feels like no one is fighting for us. Maybe we will yet squeeze a few drops of democracy from this lemon, even if its sour taste lingers. Maybe we will reinvent ourselves one more time, and make our administrative region special one more way.