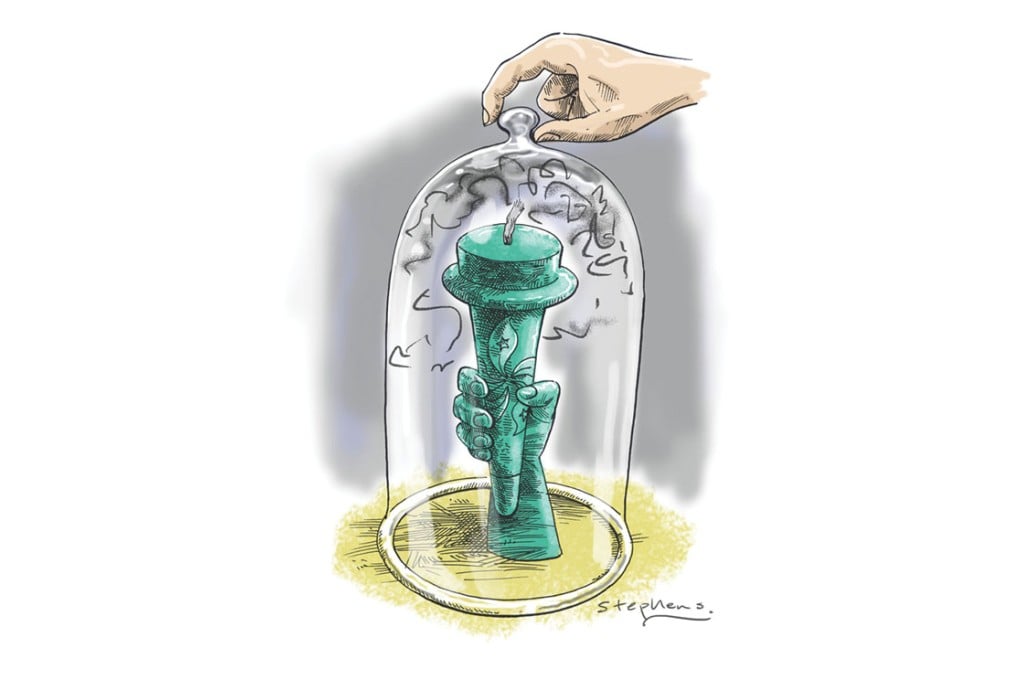

In today's China, is democracy even possible?

Chang Ping says the Hong Kong debate on universal suffrage raises the fundamental question of whether real democracy is ever possible today under a modern autocracy

Chu Anping, the renowned liberal scholar and journalist who was persecuted and "disappeared" during the Cultural Revolution, once said: "Under the Kuomintang's rule, democracy is a matter of degree, of having more or less democracy. Under communist rule, it is a choice between some and none."

Only two weeks ago, the debate in Hong Kong on how to implement universal suffrage in the 2017 election centred on a question of degree - namely, what kind of arrangements would be the most democratic. On August 31, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress presented the Hong Kong people with the choice of "either/or" - either Hong Kong accepts an electoral framework that is far worse than it had hoped for, or there'll be no universal suffrage.

On the face of it, this isn't a hard choice to make: some is better than none, and a tiny bit of progress is still progress. But Hongkongers should understand that such limited universal suffrage isn't new even in mainland China.

By law, some 500,000 villages on the mainland elect their own village chief and members of the village council through a "one man, one vote" system. According to the law, "no organisation or individual may appoint, assign or replace the village committee members" and "registered voters may directly nominate candidates".

Direct elections extend even to the lower rungs of the NPC. These include the representatives to the legislatures for districts that are not part of a municipality, counties, autonomous counties, townships, ethnic townships and towns. Not only are these deputies elected by "one man, one vote", political associations and civic groups may also nominate candidates for election. Even regular voters who wish to nominate their own candidate may do so - a group of 10 can jointly propose one.

In other words, the civic nomination that Hong Kong's pan-democrats have been fighting for has long been practised in mainland elections. China has even experimented with the direct election of the heads of townships and towns.