Scots' desire for change cannot be ignored

Niall Fraser says Scots should ignore the desperate last-gasp attempts by UK leaders to win them over and instead embrace the historic opportunity for change on offer through a vote for independence

Today, the country where I was born and raised stands on the edge of history. In a few hours, 4.2 million people who live and work in Scotland - a remarkable 97 per cent of those eligible to vote - will begin to exercise their constitutional democratic right to shape the course of history by marking a cross on a piece of paper.

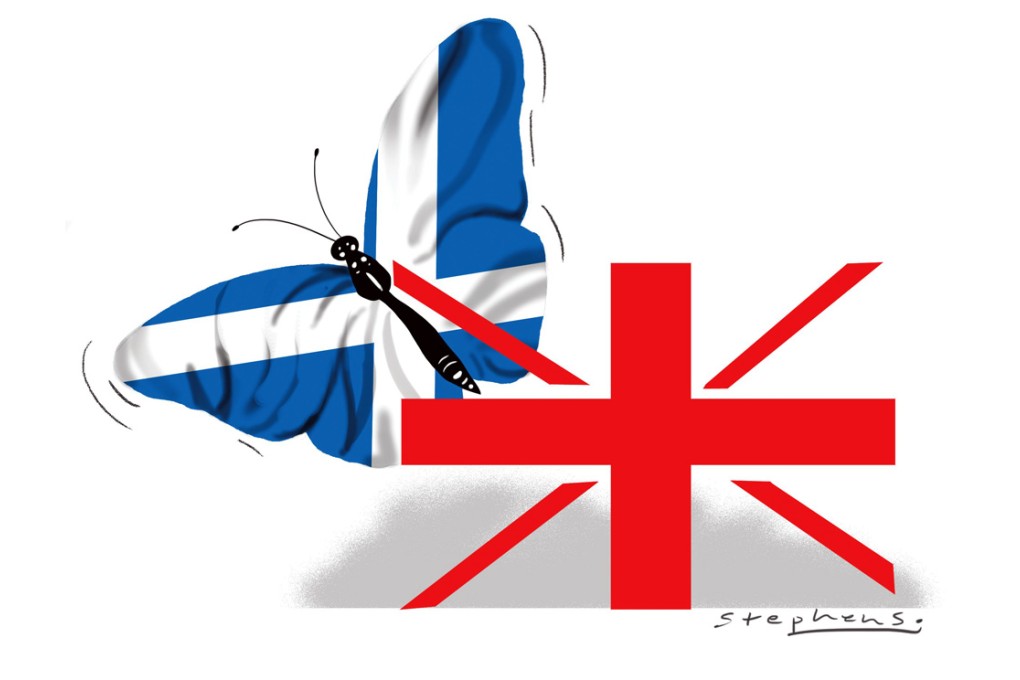

How special is that? No one has died, or even come close, in the politically charged, three-year run-up to this once-in-a-lifetime poll that will - one way or another - change the political landscape of Britain forever, rattle Europe and have ramifications for the rest of the world.

Until three days ago, my answer to the question on the ballot paper: "Should Scotland be an independent country?" was a steadfast "No". The world already has too many borders and divisions that set people against each other, accentuating differences when in fact we have more in common than that which sets us apart. Why create yet another wall, I thought.

But things have changed. We all have values instilled in us by those who brought us up. Sure, we play fast and loose with them, shaping them to suit our selfish desires, but a few stick and, no matter how much we try, they refuse to budge.

The unbending value I had drummed into me was that you can't have the best of both worlds. Not only is it a selfish and dishonest desire, it's impossible to attain. There is only one world and time will find you out.

By definition, the only thing worse than expecting the best of both worlds for yourself is promising it to someone else. But that is precisely the desperate card the men who think they run the United Kingdom - Prime Minister David Cameron, his sidekick in the coalition government Nick Clegg and the leader of the opposition Labour Party, Ed Miliband - attempted to play as it finally dawned on them that a "No" vote in Scotland wasn't assured.