The Gazza show: Paul Gascoigne makes a movie as he struggles to make ends meet

A movie about Paul Gascoigne, produced by him, tries to clear the air about his battle with demons but critics dismiss it as a quick-buck vanity project

Once upon a time in Gazza la-la land, getting an audience with the clown prince of football was free.

England's favourite son, Paul Gascoigne, willingly entertained anyone, anywhere, anytime, such was his pathological, childlike-need for attention.

Not any more. Twenty-five years to the week after one of the most talented players to put on a Three Lions shirt blabbed patriotic tears during the 1990 Italia World Cup, Gazza has wised up.

Sorry, Gazza won't do any interviews unless he is paid - £3,000 face to face or £1,500 for a phoner

Sober and correct, he's cashing in on his misfortunes, exploiting the media that so often milked his foibles and tortured soul during decades of madness: the drink, the drugs, arrests and blur of revolving rehab doors.

The maverick former Newcastle, Spurs, Lazio and Glasgow Rangers midfielder is back in the headlines promoting his new film, .

The film was made at his request and is partly produced by him because, he says, he can't trust the media to set the record straight - especially the British tabloids, which, he argues, drove him over the edge with their relentless intrusions.

This month he received £190,000 (HK$2.3 million) in compensation from the Mirror Group, which hacked his phone for 11 years.

His fortune long-ago squandered, he complained to the court the settlement was not enough to make up for the harm caused.

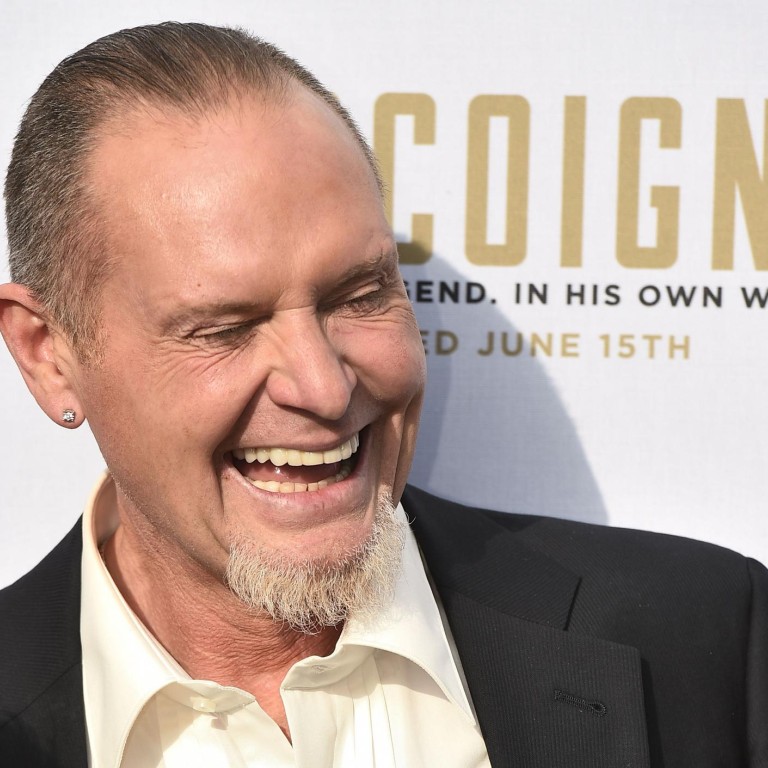

So much now rests on the financial success of his movie, which is out on DVD after a "one-night-only" cinema release stunt. He is plugging it earnestly on Gazza-friendly TV chat shows, during which he habitually (read: nervously) stokes the odd-looking grey-white goatee beard he now sports.

If he hasn't sued you or your editor, he will grant you an audience, but at a price.

"Sorry, Gazza won't do any interviews unless he is paid - £3,000 face to face or £1,500 for a phoner," says his agent, Terry Baker. Suggesting an interview would help promote his documentary in the huge China market, where he has many admirers after his adventures there, Baker replies: "You all say that. Now it's all about the money. He has to earn a living and he won't speak unless he is being paid."

It's certainly an enthralling morality tale, demonstrating how genius can be an ephemeral and destructive force.

But there's nothing revealing or which adds to the real-time Gazza tragicomedy.

There is previously unseen footage of the player as a youngster at Newcastle, and of Italia '90 on which the film pivots.

Following his and the teams' heroics in the semi-final against Germany, the squad came home to 500,000 waiting at the airport, most to cheer Gascoigne; Gazzamania had taken hold.

But instead of launching the player on the path to true greatness, it signalled the start of his exponential descent into selfobsessed destruction.

The groupies took a leach-like grip of the susceptible, mixed-up boy masquerading as a fun-loving, cheeky, plastic-breast-wearing, sensational stalwart.

But that's not the plot played out in the film, which fails in its task to "put the record straight". Instead, it smacks of victimhood.

"Gascoigne" the movie, instead, extends the portrayal of a Shakespearean figure, a prince among mediocrity who can no longer live on his wits and instead must scrape by on past glories.

History is sanitised and much of his maddening existence given an Orwellian rewrite. The misery that blighted Gascoigne and his loved ones is repackaged with slick, contrived camera techniques and censored narration by selected talking heads.

There is no word from his influential childhood friend and drinking partner Jimmy "Five Bellies" Gardner, or from his influential, avuncular ex-England and Tottenham manager Terry Venables, not a peep from fellow players like Chris Waddle. There is no mention of his past agents and cronies, his celebrity friends, his ex-wife and children or the journalists who charted his career.

Instead, former teammates Gary Lineker and Wayne Rooney, and Chelsea boss Jose Mourinho add some stardust with soft-focus tributes that dance too close to pity for comfort; Mourinho declares Gazza "the special one". Even this saccharine gloss fails to mask glaring omissions.

He innocently wonders why he and the lads were pilloried for drunkenly ripping up their official Three Lions T-shirts - "letting their hair down" as Gazza calls it - days before the biggest tournament of their lives on home turf.

He neglects to mention the vandalising of the Cathay Pacific first-class cabin by him and his teammates. He does not mention his being drunk and restrained from entering the cockpit.

He fails to recount how one drunk player was put in the overhead luggage hold and fell out on to a Hong Kong stewardess, causing injury that required medical attention and time off work.

Nor does the film mention the last time I saw him in 2003 in the Chinese hinterland.

I had been sent to record his debut for Gansu Tianma, a motley assembled team playing at the bottom of Jia Division B on the industrial satanic banks of the Yellow River in Lanzhou.

Gazza, after years of negative headlines had decided for the princely sum of £500,000 to kick-start his player-coaching-managerial career in a remote Chinese city covered in Gobi Desert sand.

This most unlikely football missionary arrived on China's frontier sober "looking lean but drawn", I wrote at the time.

I spent the match watching - he scored a beauty, assisted in another and won a penalty - with Jimmy "Five Bellies" and another pal simply known as "Hepps".

They had been helping Gazza settle into his four-star apartment and start anew; far-flung China was seen as the perfect place to reinvent himself.

But Jimmy and Hepps were leaving the next day and you could sense the anticipation. Weeks later, the isolation and culture shock pounced, calling Gazza's demons once more to arms.

He was spotted in transit at Heathrow airport, wearing lipstick and drinking heavily - stoned on booze and medication and carrying a Gucci overnight bag. He was on his way to rehab in the US, having fled Lanzhou, by some accounts, leaving his apartment lights and TV on.

His disastrous China sojourn marked a new low, a catalyst that a few years later led to yo-yoing with the ultimate self-destruction, death.

Yet this pivotal chapter is whitewashed.

On close examination, Gascoigne's film version of himself is little more than an extended selfie for our narcissistic times and is being correctly dismissed as a quick-buck vanity project, rather than a thoughtful piece on the reflections of a flawed genius who remains as vulnerable today as he was 25 years ago.