The Great LOL of China | Chinese Film Series Review: Meng Zong Cries for Bamboo

Despite increased attention to Chinese cinema, many Westerners still miss out on many good films from China. When Chinese films go unnoticed and unappreciated, I feel a compulsion to share with others.

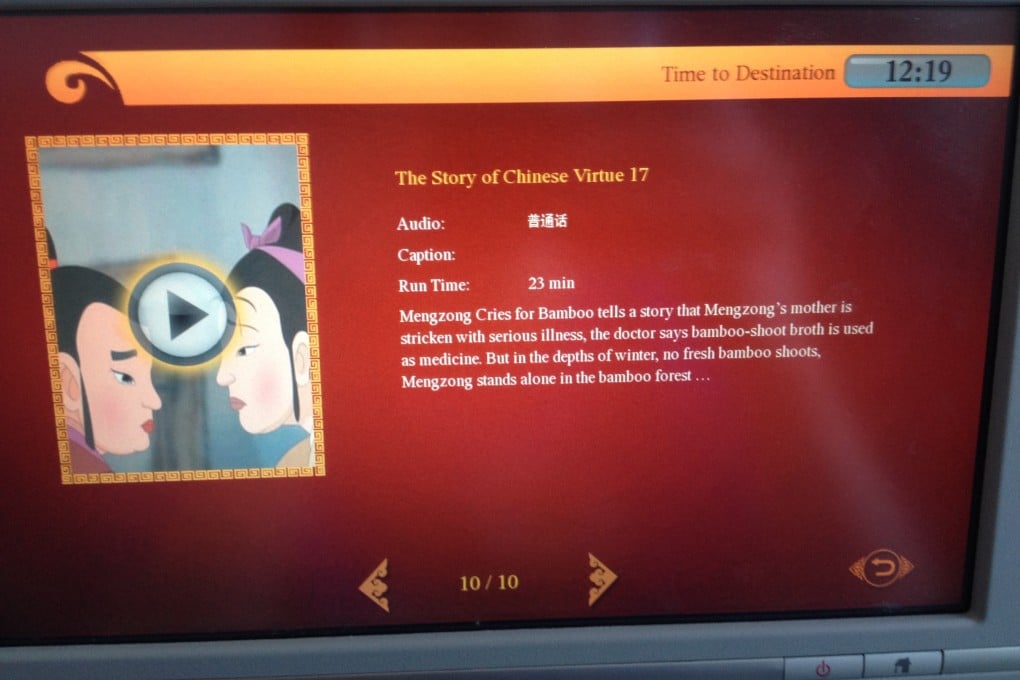

Today, I share my review of Meng Zong Cries for Bamboo, an eighteen-minute animated short I discovered under the “Moral Stories” tab in the entertainment menu on my Hainan Airlines trans-Pacific flight. Seventeenth in a series entitled “The Story of Chinese Virtue”, it is safe to say that not only have no Westerners ever seen this piece before, it is likely that no Chinese have either.

For the sake of full disclosure, I discovered, watched, and reviewed Meng Zong Cries for Bamboo while subsumed in a mental fugue state brought on by jetlag, airplane restlessness, and two cans of warm Snow Beer.

Set in the Three Kingdoms period, the film begins with an establishing shot of Meng Zong’s mother struggling through a bamboo forest, her back bent under the heavy burden of bearing two buckets of water to the village. Suddenly, she falls, cart wheeling cartoonishly through the forest.

The director (whose name is inexplicably and inexcusably not present in the opening credits sequence) makes the clever artistic choice of setting MZCfB in a world where the laws of physics are as transient and unreliable as the political reality of the Three Kingdoms Period. Meng Zong’s mother rolls for about thirty seconds down a plane with an incline of no more than five degrees. Her protracted anguish symbolizes the family’s helplessness in the face of the physical and political challenges of the time.

Meng Zong, a short, squat androgynous child with a penchant for lipstick and a bold face tattoo, leaps into action in a fit of filial piety. After bandaging up his (her?) mother, he (she?) bemoans the sad state of the region’s transportation infrastructure: if there were a road through the bamboo, his mother would more easily bring water to the village. He urges a bold plan: chop down the bamboo forest, and build a road to the well.