The Hongcouver | No Chinese, Asiatics or Negroes: racist rules of Vancouver pioneer revealed

Property tycoon Jonathan Rogers would not be impressed by today’s Chinese-dominated market

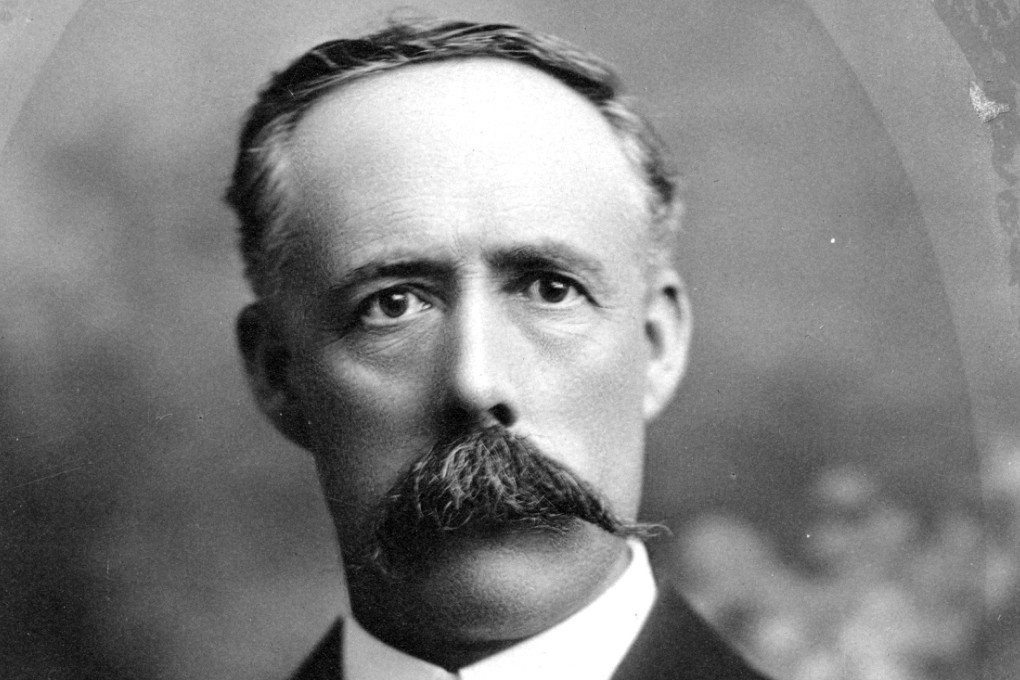

The City of Vancouver that pioneering property magnate Jonathan Rogers helped build was very different from the multi-cultural Canadian metropolis of today, with its soaring property market dominated by rich Chinese buyers.

And Rogers would not have approved.

An 86-year-old covenant that Rogers attached to the sale of one of his many properties has revealed that he tried to ban any “Chinese, Japanese or other Asiatic” from ever owning or living on the site.

The home, which Rogers sold to housewife Fannie Smith for C$775 in 1928, is back on the market for C$2.548 million (HK$17.99 million). Two offers have been made in the past month - ironically, from a mainland Chinese immigrant and a local family of Taiwanese origin.

The old document, provided to the South China Morning Post by real estate agent Wayne Hamill, casts a light on a time when Chinese immigration to Canada had been almost totally banned. Covenants such as that uncovered by Hamill, the selling agent for the home in the prosperous South Granville neighbourhood, were not uncommon at the time, he said.