How Hong Kong's history helps explain the Umbrella Movement and Vancouver’s activist evangelicals

Striking similarities between two Hong Kong eruptions, separated by 36 years, can illustrate a historical and religious context to the Umbrella Movement.

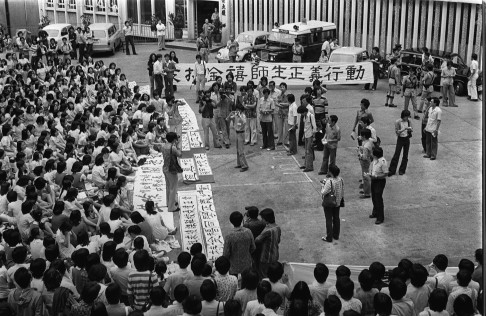

School children protesting on the streets of Hong Kong in a mismatched showdown with the powers-that-be. Sit-ins, hand-drawn banners, and appeals to human rights and dignity.

But this isn’t the Umbrella Movement, 2014. It’s the Golden Jubilee Incident, 1978.

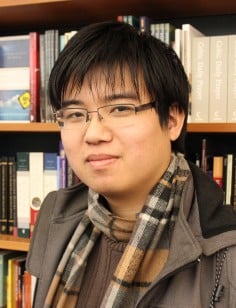

The striking similarities between the two Hong Kong eruptions, separated by 36 years, were used last week by Dr Justin Tse to illustrate a talk at UBC’s Regent College in which he presented historical and religious context to 2014’s Umbrella Movement.

And history, Tse argued, helps shed light on aspects of Vancouver’s public arena too, especially those parts involving Chinese Christians.

Much has already been made of the evangelical Christian connections that permeate the 2014 protests. From Joshua Wong Chi-fung to Benny Tai Yiu-ting, evangelical Christians have been at the forefront.

Yet Tse doesn’t argue that the Umbrella Movement is an evangelical movement, or even that evangelicals (in Hong Kong or Vancouver, for that matter) necessarily support the movement. Instead, he argues that it was evangelicals who helped created the Hong Kong public sphere in which the Umbrella Movement exists, framing their political activities in terms of their Christian beliefs.

Tse traces this back to the 1970s and evangelical activist Josephine So Yan-pui, co-founder of the Breakthrough Youth Movement. “It was then that evangelicals in Hong Kong began to take seriously their role in the public sphere,” said Tse, a former Vancouver resident.

He harked back to 1978, when outrage over the expulsion of suspected “leftist” pupils at the Precious Blood Golden Jubilee Secondary School, a Catholic girls’ school, triggered a month-long sit-in by hundreds of students and teachers at the Hong Kong Cathedral Compound. The colonial government eventually intervened and shut the school down. Josephine So and Breakthrough were involved, calling for dialogue and seeking the re-opening of the school.

“[For So] this was really about the ‘human rights’ and ‘human dignity’ of the students because they were all ‘made in the image of God’ and had political agency, so decisions shouldn’t be made by elites in cahoots from above but by the people themselves,” said Tse.

“Pair that now with Joshua Wong: ‘I believe in Christ, I believe everyone is born equal. And they’re loved by Jesus’,” he said, quoting the teenage leader of the Scholarism movement.

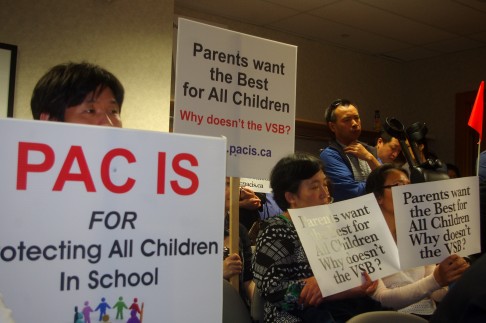

Yet the 2014 protests drew plenty of opposition from evangelical quarters; in Vancouver, a vocal portion of the Chinese evangelical community has circulated emails criticising the protesters.

This history offers a better understanding of the sometimes-controversial activities of conservative Chinese evangelicals in Vancouver. Explaining these activities in purely cultural terms – as if to say that Confucian values have predisposed all Chinese Christians to family values, and thus moral panics about homosexuality (for instance) – is a mistake, according to Tse.

In remarks after his talk, Tse said the conservative strand had developed “a privatised understanding of identity…the Umbrella Movement is a very scary thing for them because it is a very public understanding of identity”. This same “circle-the-wagons mentality” led some evangelical conservatives in Vancouver to perceive themselves and their private beliefs as under siege. Yet assuming that such thought defined all Chinese evangelicals, in Vancouver or elsewhere, would be a mistake, said Tse.

“The story that I am telling is that that conservatism is not the whole story, it certainly is not the wholesale importation of homeland politics to Vancouver, and it most certainly is not the only way to be an evangelical in this trans-Pacific Hong Kong evangelical public sphere. The Umbrella Movement bears witness to that.”

The Hongcouver blog is devoted to the hybrid culture of its namesake cities: Hong Kong and Vancouver. All story ideas and comments are welcome. Connect with me by email [email protected] or on Twitter, @ianjamesyoung70