Critical reflection needed on national education

C.K. Yeung says opponents of national education should see past their fear of brainwashing to give Hong Kong's youth a chance to know more about China's history - so they may question and debate it

The "brainwashing" tag and the almost sinister overtone that has been attached to national education show just how badly Hong Kong needs a healthy dose of it.

This is particularly so for our young who know so little about China's past and present, about its unspeakable sufferings and heartbreaking humiliations over the last 150 years, about how it manages to arrive at where it is today, and the price and sacrifices that the people and the country have paid along the road to national success.

The promotion of national education in Hong Kong should not have been a Beijing- imposed "political assignment" on the Hong Kong government. It is as ridiculous as it is sad that, while the world is hungry for knowledge and understanding of a country that is home to one-fifth of the world's population and its second-largest economy, we in Hong Kong are rejecting this need. Young people in Hong Kong know so little about China that getting to know it is as essential as learning addition and subtraction.

The starting point for our national education is facts - facts of history. Sadly, Chinese history is now no longer a compulsory subject in our schools.

Nobody can argue against the need to know history, especially the history of one's own country. And the natural way to raise national consciousness is to know the story of our country, warts and all. This last qualification is important, for no country is perfect, least of all advanced Western democracies. The British can never shake off the opprobrium of their conduct in the opium war and their plundering of weak nations. The Americans, too, have blood on their hands - the genocide of native Americans, racial lynching, and the war against imagined weapons of mass destruction. China as a country has few sins, but the Communist Party does have many failings. They are invaluable national education lessons.

Hong Kong's present-day parents were young students during the British administration. The very first English-language song that I learned as a student was which we sang high-spiritedly at assembly. When the British destroyer HMS Sheffield was sunk in the Falklands war in 1982, some Chinese students wept openly as they watched the news on television. We learned sanitised British history, minus its warts, and nobody dared to say boo.

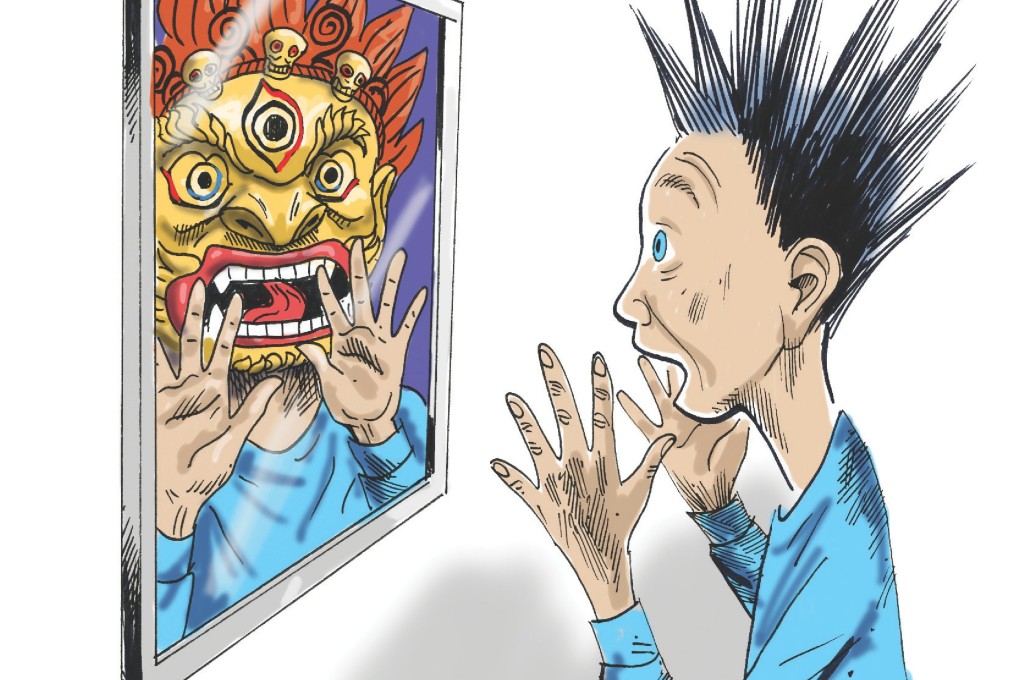

We open our hearts to Western values wholesale, including their hidden biases. They have seeped deep into our psyche: that West is best, and East is beast. In no other place in the world is the idea of learning about one's own country so alien, even repugnant.