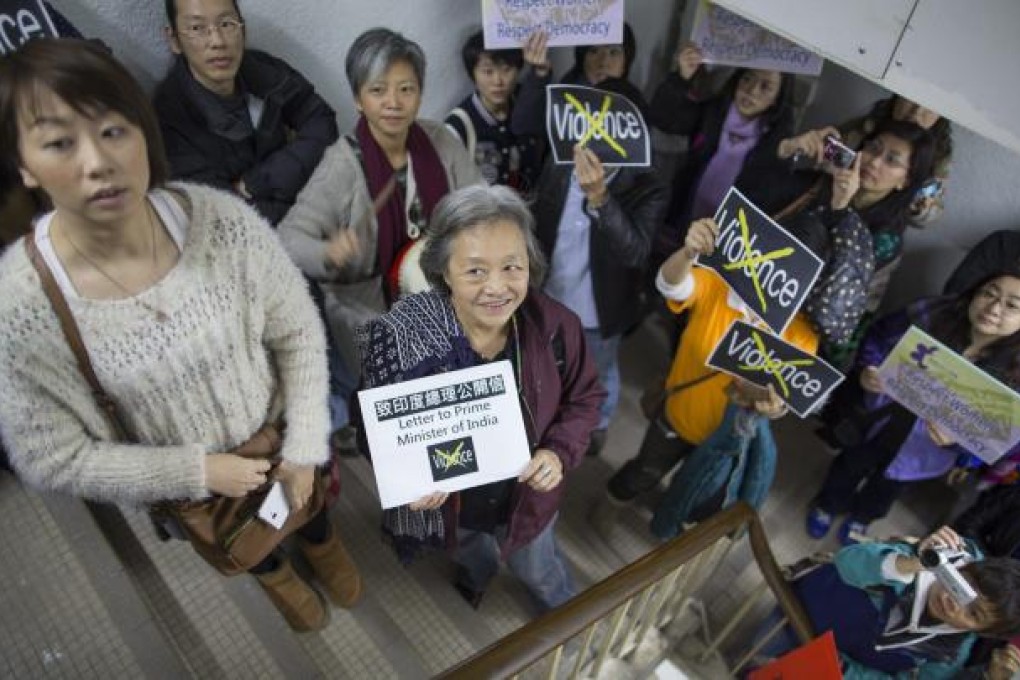

Time to redress inequalities in Hong Kong's rape laws

Surya Deva says the shocking case in Delhi should also spur us to act

The recent gang rape of a 23-year-old student on a bus in Delhi has rocked India. While India's economic growth may be slowing, there has been no such effect on the growth in the number of rapes. Since 1971, when the National Crime Records Bureau started collecting data, the number has increased over 873 per cent: from 2,487 in 1971 to 24,206 in 2011. Even if we factor in population increase and consider that more women may be willing to report rape now, this kind of growth is alarming to say the least.

The free-market economy and the consequent relaxation of socio-cultural norms have empowered women in multiple ways. However, this change has also made women an easier target of rape and other kinds of sexual discrimination, because the infrastructure as well as legal and moral norms required to protect the autonomy of empowered women has not evolved.

Rapes in India and elsewhere should be seen as part of a wider culture of discrimination against women - from female infanticide to genital mutilation, dowry deaths, sexual harassment, domestic violence, unequal access to education and health facilities, inequalities in employment, pay and promotion, and inadequate representation in corporate boards, courts and political institutions.

While Hong Kong's rape statistics cannot be compared with those in India, both former British colonies continue to have a discriminatory definition of rape and other sexual offences. In fact, the Hong Kong courts have already declared unconstitutional two discriminatory provisions of the Crimes Ordinance concerning homosexual buggery.

Nevertheless, discrimination persists in Section 118 of the ordinance, which defines rape as a "man" having sexual intercourse with a "woman" without her consent. This one-dimensional definition is unsuitable for the modern time when both the victim and offender can be either a man or a woman. Gender should be irrelevant to the offence of rape, as it is for most other crimes.

Another problematic part of Section 118 is that it regards the male sex organ as central to the definition of rape. If the objective is to protect, the definition should be victim-centric, rather than focusing on the means of committing the offence.