The lessons of Sars, 10 years on

Margaret Chan says the mode and speed of the deadly spread of Sars 10 years ago did catch us out, but we should remember it today for how the world rose to the challenge to contain it

Ten years ago, on March 12, I sent an urgent e-mail to the World Health Organisation. I was in charge of Hong Kong's Department of Health at that time. We were screening more than 50 hospital staff for symptoms in a mysterious outbreak of flu-like illness. I was alarmed for two reasons. First, these were health care workers, the lifeblood of health systems everywhere, and some were extremely ill with pneumonia. Second, the cause could not be identified. The mysterious nature of the outbreak bothered me deeply, as I believed that Hong Kong's laboratories and scientists were among the best in the world. That view was subsequently confirmed internationally as events unfolded in what became a nightmare experience for me, Hong Kong, and the world.

That same day, the WHO used the internet to alert the world to Hong Kong's outbreak and a similar outbreak at a hospital in Hanoi, where 25 staff were acutely ill with pneumonia or severe respiratory illness, and five were in critical condition. Media coverage of the WHO alert was intense, and that set the alarm bells ringing in hospitals the world over. Vigilance - and anxiety - were high.

More bad news came the following day, when authorities in Singapore reported atypical pneumonia in three young women who had recently returned from a stay in Hong Kong.

By March 15, it was clear that the first new disease of the 21st century was spreading explosively along the routes of international air travel. At 2am, the head of the WHO outbreak alert and response team received an urgent call from Singapore. A doctor who had treated the first cases there was attending a medical conference in New York. He, too, had fallen ill with similar symptoms and was flying home. WHO traced the airline and flight details. At a stopover in Frankfurt, the doctor and his two travelling companions were identified and immediately placed under medical care. They would become Germany's first cases. On the same day, Canada reported its first cases of atypical pneumonia.

The WHO issued a stronger alert. It named the new diseases after its symptoms: severe acute respiratory syndrome. The WHO defined characteristic symptoms and asked all travellers to be alert to what it called "a worldwide health threat".

As details about the earliest cases began to emerge, Hong Kong was again in the spotlight. All of the earliest outbreaks, outside mainland China, could be linked to a single location: the ninth floor of Hong Kong's Metropole Hotel. They could further be linked to a single event: a one night's stay, on February 21, by a physician who had treated pneumonia patients at a hospital in Guangzhou. He was admitted to hospital the following day and died soon after. In a classic piece of detective work, Hong Kong's Department of Health epidemiologists linked that brief stay to 13 infections that seeded the outbreaks in Hanoi, Singapore, Toronto and Hong Kong, starting chains of transmission that would eventually affect thousands.

In the four months following the March alerts, Sars closed schools, businesses and some borders. Air travel to Hong Kong and other severely affected areas seemed to halt overnight. Tourism dried up. Consumers stayed at home. Economic losses mounted into the millions and millions of dollars. By the time the outbreak was declared over, on July 5, nearly 8,500 people had been infected and nearly 800 had died.

Those four months were heartbreakingly hard. But they were also a time of triumph. Rarely has the world shown such solidarity. Scientists from multiple countries put aside their academic rivalries and collaborated around the clock sharing all they knew, all their special tricks of the trade. Hong Kong scientists were instrumental in identifying the causative agent - an entirely new coronavirus - and devising the first diagnostic tests. Top scientific journals set aside their rules about content access and expedited publication dates to ensure that new knowledge about the disease was immediately available to all. Clinicians spent long hours in teleconferences, sharing knowledge about symptoms and treatments, trying to unravel the mysteries of the new disease.

I remember Hong Kong's empty streets and the masked faces of the few who ventured out. I remember the funerals of health care staff who died following their dedicated care of patients. But I also remember the clean-up campaigns, the volunteer groups and the civic initiatives of support. I remember collaboration from all parts of society, like the police who contributed an electronic tool, developed to track criminals, that greatly facilitated the tracing of patients' contacts to find those with symptoms and give them care.

I remember the sudden explosion of cases in the Amoy Gardens housing estate in early April and how that event prompted an unprecedented isolation order to prevent further spread. I remember, too, the almost instant expert speculation from abroad that the explosion of cases at the housing estate was proof that the Sars virus was now airborne. I remember the emergency investigation, conducted by the Department of Health and eight other government agencies, that quickly proved that rumour false, calmed down the panic, and helped the people of Hong Kong cope. Though that event has been investigated by multiple other research groups, no one has ever challenged the conclusions reached by the Hong Kong teams.

Sars revolutionised our understanding of the power of real-time communications. During the outbreak, the WHO issued daily situation updates, keeping the public and the media fully informed, as knowledge about the disease and effective measures for control began to emerge.

One set of statistics defines this power well. The WHO alerts provided a clear line of demarcation between the earliest outbreaks, in China, Hong Kong, Hanoi, Singapore and Toronto, all of which were severe, and the 26 additional countries and territories where cases subsequently occurred. Areas with outbreaks before the alerts began on March 12 accounted for 98 per cent of the global total number of cases and 79 per cent of total deaths. The other 26 sites, characterised by high levels of vigilance and preparedness, were able to prevent further transmission or limit it to just a handful of cases.

Sars also shattered the notion that countries blessed with high standards of living and top medical care were somehow invincible to the threat from new diseases. Sars was largely a disease of wealthy urban centres. The virus spread fastest and most efficiently in well-equipped hospitals.

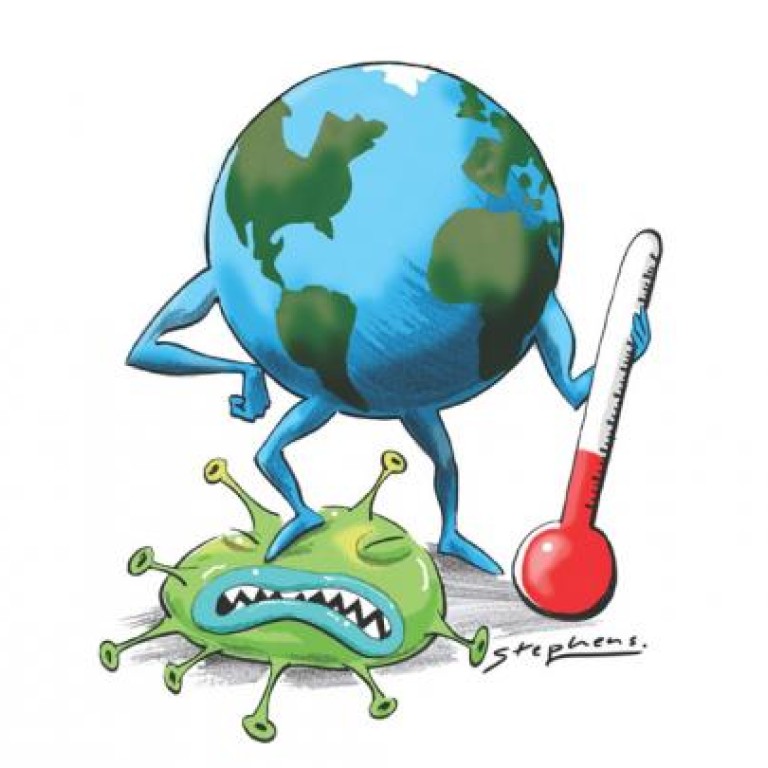

Sars taught the importance of meeting an emergency with whatever tools are at hand. Sars was a 21st-century disease in its mode and speed of spread. But it was eventually defeated using the 19th-century tools of case detection, contact tracing, isolation and infection control.

In the view of some, the humble thermometer was the weapon that broke the chains of transmission.

In the end, Sars was a story about human ingenuity and determination, about a world united by a shared threat, about how a lethal new virus could bring out the best in human nature.