Wind of change

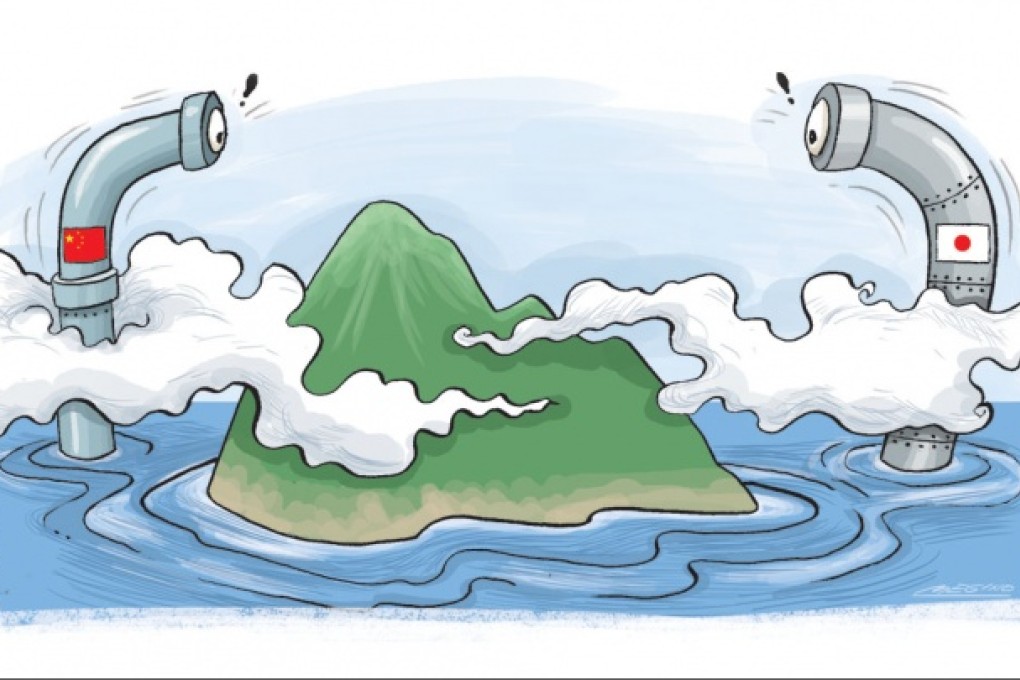

Philip Cunningham considers why, as China rises and American power wanes, the US-engineered fog of ambiguity over the status of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islets is losing its hold

The United States should urge Japan and China to “avoid any steps that might escalate tensions in and around the disputed islands”, says Sheila Smith of the US Council on Foreign Relations. It’s a view that resonates in Washington, but is it not the pinnacle of hubris for the US to chide China and Japan, as if they were schoolchildren fighting over a rock, when the US is part of the problem?

US cold-war strategy created the Senkaku/Diaoyu conundrum in the first place, with the Nixon administration fixing it so Japan had de facto control while not denying Chinese claims to the territory. Ambiguity of this sort served to wrong-foot both China and Japan, while seeming to cede the disinterested high ground to the US. It’s been equivocation wrapped in ambiguity ever since.

So far, Barack Obama’s Team America has only muddied the waters, modelling US-Asia strategy on a clumsy ball-court move; the problem is the “pivot” has been anything but a slam dunk. With Uncle Sam’s pivot foot trapped in the drone-war zone along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, the other foot dragging in Pacific waters, the feint-to-the-East strategy has rattled China without scoring any points for the allies. Instead it has riled the region, where the response has been to ratchet up defence and military spending.

The pivot – fancy footwork going nowhere – is classic Obama, all finesse but no success, as Shinzo Abe and Xi Jinping up the stakes and face off over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islets. The US is and isn’t committed to defending Japanese sovereignty, a hazy, lazy policy that could drag America into a ruinous battle along the fault line of the world’s three largest economies.

The ambiguous trilateral arrangement brokered by Nixon’s team lasted as long as it did because of the relative weakness of China and the formidable forces the US put forward in the region.

In 1945, the US won the war but lost the peace with Japan, where the imperious mentality has found new fields of dominion, and where the war has been continually invoked and revised by the entrenched right-wingers and Yasukuni cultists who rally around Prime Minister Abe.