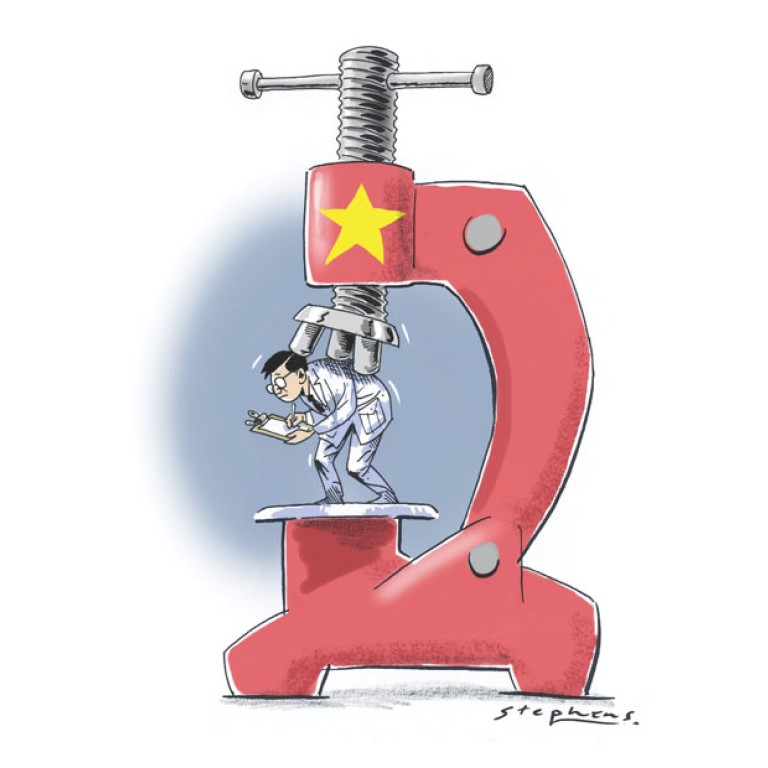

China can't stem brain drain without revamping its research culture

Cong Cao says Beijing's determination to lure back overseas Chinese talent should go beyond financial incentives; it must be matched by a resolve to create a truly open research culture

The threat of a "brain drain" has long lingered over China's ambitions to transform its economy from one reliant on low-cost manufacturing to one powered by home-grown innovation. Alert to the danger, Beijing has acted swiftly to counter the departure of its scientific and entrepreneurial talent overseas.

Back in 2008, the Chinese Communist Party turned headhunter when it launched its "Thousand Talents" scheme to tempt the brightest and best Chinese back to their homeland after periods studying and working abroad.

The policy was designed to attract, in 10 years, through generous salaries, start-up packages, housing and tax incentives, 2,000 established academics and entrepreneurs with overseas PhDs and research experience.

On fleeting inspection, the programme is a raging success. Quotas are overfulfilled: 3,300 returnees have been recruited in less than five years. The initiative has lured some of the best academics back to China. Biochemist Xiaodong Wang, elected to the US National Academy of Sciences at the age of only 41, is a notable catch.

But scratch faintly at the surface and the gaping cracks appear. The real cream of Chinese talent is still hungry for a life overseas. And once they have experienced it, they rarely return.

Statistics released by the US National Science Foundation show that, over the past three decades, Chinese have been the top foreign recipients of doctoral degrees in science and engineering from American universities. Upon receiving their PhDs, nearly all the students indicated their intention to remain in the US - more than 90 per cent have managed to stay.

Meanwhile, China has witnessed a growing exodus of its top graduates. In 2006, Tsinghua University and Peking University leapfrogged the University of California, Berkeley to become the two largest baccalaureate-origin institutions of science and engineering PhDs in the US.

The global financial crisis served to steer more overseas Chinese students back to their homeland. However, this has not equated to an influx of leading lights. According to a 2008 Duke University survey of 637 Chinese returnees, half had five years' or less experience in the US.

In other words, the US experience of these returnees was limited. And herein lies the root of the controversy surrounding the Thousand Talents programme, which is fuelling discontent within China's domestic science community.

Scratch at the surface and cracks appear. The real cream of talent is still hungry for a life overseas

The initiative is reserved for those with foreign degrees and experience at the expense of domestically trained scientists. But not everyone recruited by the programme can be classified as "top talent". Many younger academics are untested. With just a couple of years of post-doctoral experience, they can return to China to become full professors, commanding a pay package several times higher than that of a new hire of the same rank. Some returnees have reportedly taken advantage of this blind worship of foreign experience, embellishing their overseas credentials to sneak into the programme.

Many of the academics appointed to the scheme seldom work full-time at their Chinese institutions. Some are only based in China for two months a year. It is an open secret that a number of them hold two positions concurrently: one at a Chinese institution and one overseas. This is why the full name list of the Thousand Talent recruits has never been made public.

This scenario breeds corruption. In May, three Chinese researchers at New York University were charged with taking bribes from Chinese medical and research institutions for details about NYU research into MRI technology.

Unsurprisingly, this has only succeeded in chipping away at the morale of China's scientific community. Tensions between those with and without foreign experience are rising; in 2011, recruits from the Thousand Talents programme were all voted out of the elite membership of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

So, why are China's first-rate academics reluctant to return home to participate in the country's expected rise to superpower status?

China remains a society that revolves around personal relations, or . After spending a long period overseas, academics are unlikely to have maintained a strong set of personal business relationships, which in turn reduces their access to sources of research funding.

Since many Chinese scientists have no experience of carrying out research in an international setting, returnees may experience another culture shock: they struggle to find like-minded scholars with whom they can collaborate. The Chinese research system favours instant results and does not tolerate failure; vision and strategic thinking, which are held in such high regard in the West, are off the agenda.

This situation is improving. A special amendment to the law on the progress of science and technology was passed in late 2007, acknowledging that failure is part of the innovation process. Yet there remains tremendous pressure on scientists, including returnees, for immediate results.

There is growing evidence that plagiarism, fraud and manipulation of data are interwoven through China's research process. With the scientific community failing to take action, many potential returnees are reluctant to enter this environment.

Political obstacles also act as deterrents. Certain types of social science research are deemed politically unacceptable even though there is an understanding that China cannot afford to expand its economy without the participation of social thinkers and public intellectuals. Most of the academic returnees are natural scientists; social scientists (except economists) have not returned, and they are cautious about working even part-time in China for fear of political reprisals.

The success of government efforts to attract individuals capable of steering China along a path of sustainable development will be judged not on numbers of returnees, but on whether it can create a new research culture in which every scientist, both overseas and home trained, has the opportunity to demonstrate their value. It's a pity, then, that the problems associated with initiatives like the Thousand Talents programme have dented China's ability to attract the brains the country desperately needs to make its next stride forward.