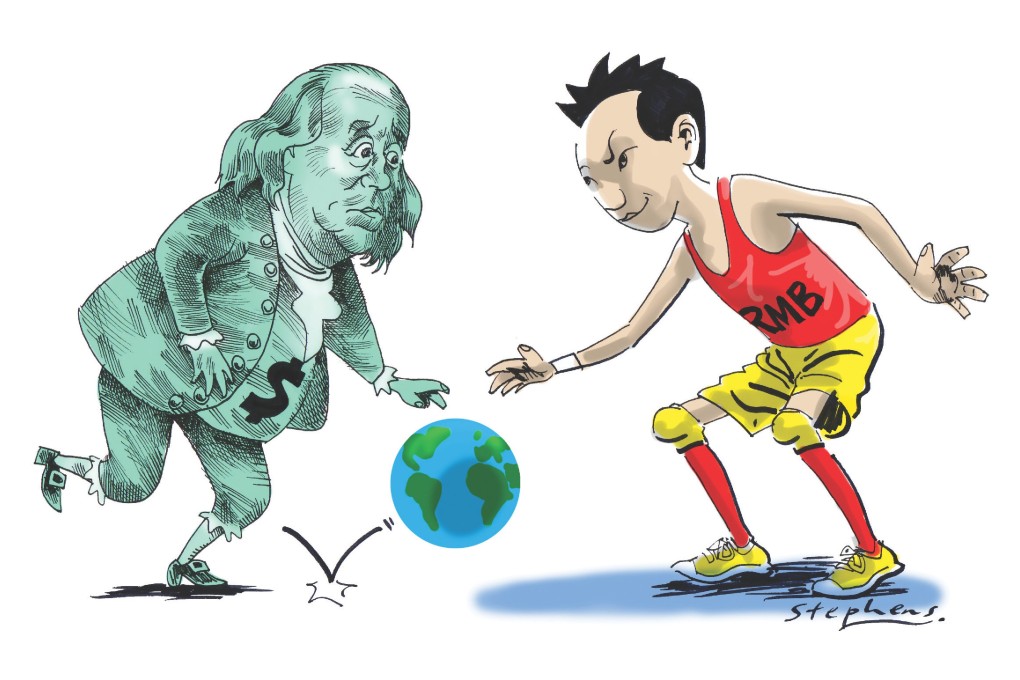

China's plans to be a global currency player on the right track

Niv Horesh says China's economic might and record of monetary management should allay scepticism overits efforts to turn the renminbi into a global reserve currency

The plan to groom London to be a launch pad for turning the renminbi into a global reserve currency remains on the drawing board. Yet, given the recent fiscal debacle in the US, market pundits might for the first time be feeling some insecurity about the long-term future of the US dollar.

That insecurity was also not just a result of the upbeat rhetoric that London mayor Boris Johnson sounded during his recent trade mission to Beijing, or talk of the British nuclear power industry being taken over by cashed-up Chinese state-owned enterprises.

China is no longer a cold war enemy, and its huge economy is closely intertwined with the West

Rather, it has to do with the streak of news for China this quarter: its economy still seems to be growing much faster than other economies. A few important new studies further suggest that the transition of the Chinese economy towards a greater share for household consumption, as compared with infrastructural and industrial investment, is happening much faster than previously thought.

In other words, Beijing's measures to curb the investment glut and manufacturing overcapacity that are associated with its post-global financial crisis stimulus package may be working, at least in part.

So the global economy's centre of gravity continues to shift steadily eastwards, and China's economy may have begun to slowly decouple from America's after decades of dependence on exports to that part of the world.

The renminbi has, however, not been floated globally, although its share of cross-border transactions worldwide is steadily growing, and although Chinese agencies have symbolically downgraded America's credit rating.

Renminbi sceptics and "China bears" often invoke the argument of China's insular financial market to explain why the renminbi is not likely to assume reserve-currency qualities before 2025. After all, China still readily buys into US dollar- denominated assets so as to help America tide over its trade surplus with China.