40 billion reasons why we may not be alone

Paul Stapleton says if even only a tiny fraction of the billions of earth-like planets in our galaxy contain life, then we really are not alone

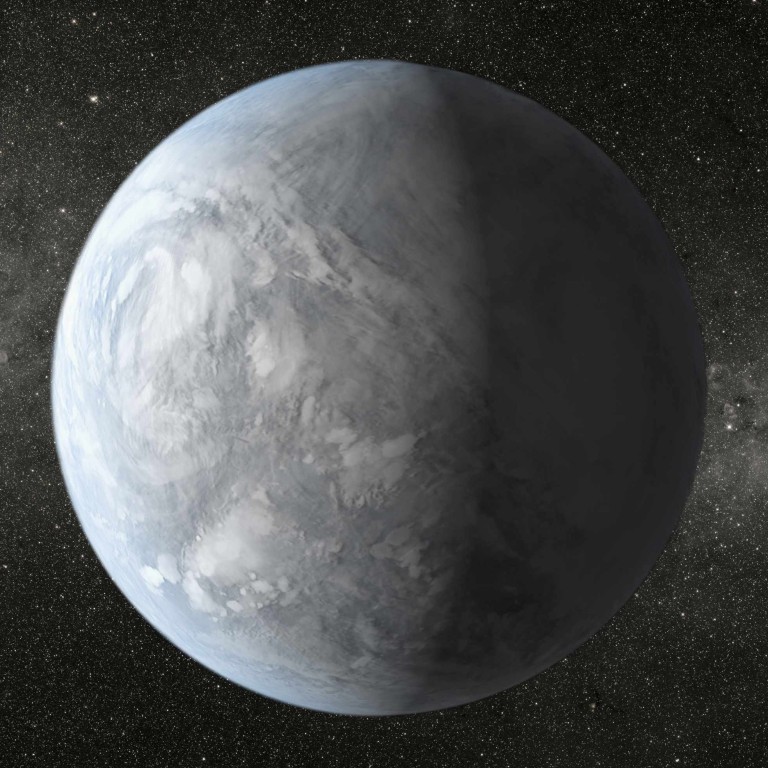

The recent news that there are 40 billion earth-sized planets in our galaxy, give or take a billion or two, suggests that the possibilities for extraterrestrial life have jumped enormously. This number is an estimate, of course, seeing that astronomers have found actual evidence of only about 1,000 exoplanets. Forty billion is a big number, however.

Coincidentally, in the same week, the discovery of another "earth-like" planet was announced, but this one has a surface temperature of up to 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit so we can probably exclude life there. This is a reminder of the "rare earth" hypothesis, which claims the conditions for life, especially intelligent life, may be extremely exceptional in the universe.

The rare life hypothesis contends that several significant hurdles must be overcome for life to gain a foothold on a planet. Naturally, many of these conditions assume life, as we know it, is based on the existence of liquid water. Thus, a planet needs to be in the "Goldilocks zone" - not too close and not too far from its mother sun. But there are other, less intuitive, requisites for life.

One of these is a good-sized moon that can keep the planet from gyrating wildly over the millennia. Ours does this for us quite nicely; otherwise, our hemispheres would frequently switch back and forth. Tropical plants would find themselves in the Arctic on a regular basis, which would be good for neither those plants nor the life that eats them.

Our moon also provides a clue to another requirement. Its cratered surface suggests that the solar system is like a shooting range for comets and asteroids. Therefore, another condition is the need for an atmosphere to break up the small rocks that come in, as well as the necessity of a large planet like Jupiter to hoover up many of the large rocks out there that could wipe out any nascent life.

Related to the protective force of our atmosphere is our magnetic field, which keeps the sun's radioactivity from frying us, and the microbes as well. In fact, these are just a few of the many preconditions for life to emerge as proposed by the rare earth hypothesis.

Now let us just imagine for a moment, however, that intelligent life is relatively plentiful in the universe, say, one planet for every galaxy, which would amount to one civilisation for every earth-like planet in a galaxy - in other words, 100 billion civilisations, if we assume there are 100 billion galaxies in the universe.

Now consider that our species, Homo sapiens, first developed art and sophisticated tools, hallmarks of intelligence, about 50,000 years ago, a mere blink of the eye in cosmic time. And let's say that each intelligent civilisation lasts a million years on average before annihilation.

There are a lot of assumptions here, but allowing them a loose leash, we can conservatively say that big, bad events such as world wars, epidemics and assassinations, as well as big, good events like cures for major diseases are happening in the thousands all over the universe, right now.

This recent news about billions of earth-sized planets could mean the universe as we know it is getting a whole lot more interesting.