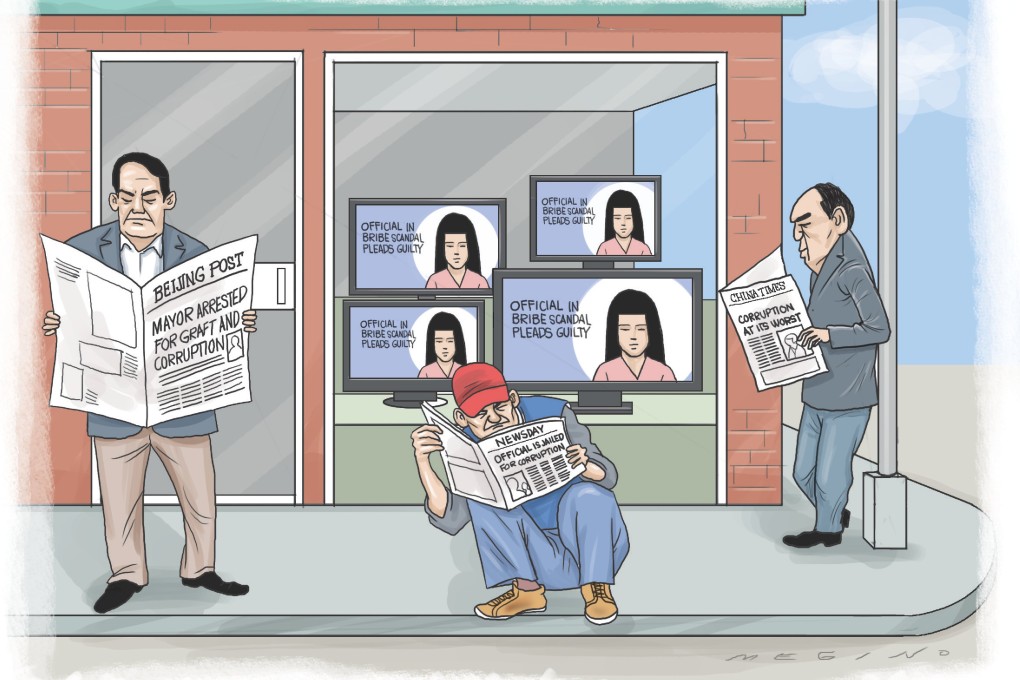

Corruption in China may appear to get worse before it gets better

Dan Hough says despite maintaining its ranking in a corruption perception index, China should brace for a probable slide, given all the attention on its anti-graft drive

This week saw the world's most prominent anti-corruption non-governmental organisation, the Berlin-based Transparency International, publish its annual Corruption Perceptions Index, the group's best-known attempt to measure perceived levels of corruption around the world.

As usual, it doesn't take a great deal of imagination to work out which countries received the best and worst scores. The Nordic states performed admirably, with Denmark scoring 91 (out of a maximum of 100) indicating that it is - according to this measure at least - "the least corrupt country" in the world (alongside, to be fair, New Zealand). Sweden and Finland were, however, not far behind, registering an eminently respectable 89 in joint third place.

At the bottom, it was a familiar tale of woe for Afghanistan, North Korea and Somalia which all ended up 175th (and last) with a meagre eight out of 100. The story wasn't much more encouraging for Sudan (11), Libya (15) or Iraq (16), all of whom clearly have deeply ingrained corruption challenges to deal with.

The index is, of course, not without its critics. Indeed, many scholars write the table off as being fit for nothing more than discussions at middle-class dinner parties. Methodologically problematic though the data undoubtedly is, the figures nonetheless get noticed by both governments and commentators. Going up or down in the table will, in other words, be noted. One suspects that applies to officials in Beijing just as much as those elsewhere.

The 2013 index, nonetheless, won't make awfully pretty reading for Chinese bureaucrats. In 2012, China ranked 80th with a score of 39. So, above halfway in terms of the rank order of countries, but well below the significant score of 50 that, according to Transparency International, signifies that a state has systemic corruption challenges. In 2013, China actually fared marginally better, remaining in 80th place overall but improving its score marginally to 40. And that despite the high-profile anti-corruption drive launched by President Xi Jinping in recent months. The picture, in other words, still does not look great.

We should, however, be a little careful before concluding (from this data at least) that the current anti-corruption campaign is not really bearing fruit. The drive might well be going nowhere fast, but that's not a conclusion we can yet draw with any certainty. The very fact that corruption has risen to the top of the political agenda in Beijing means that more and more media commentators are talking about it.