New space race tells an old tale of nations' quest for soft power

Gary Rawnsley says China and India now seek what America had

On December 24, 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders became the first humans to watch the earth rise over the moon's horizon. In a live television broadcast, the three crew members took it in turns to read the first 10 verses of the Book of Genesis. Anders' iconic photo, Earthrise, showed us just how small and fragile our planet actually is.

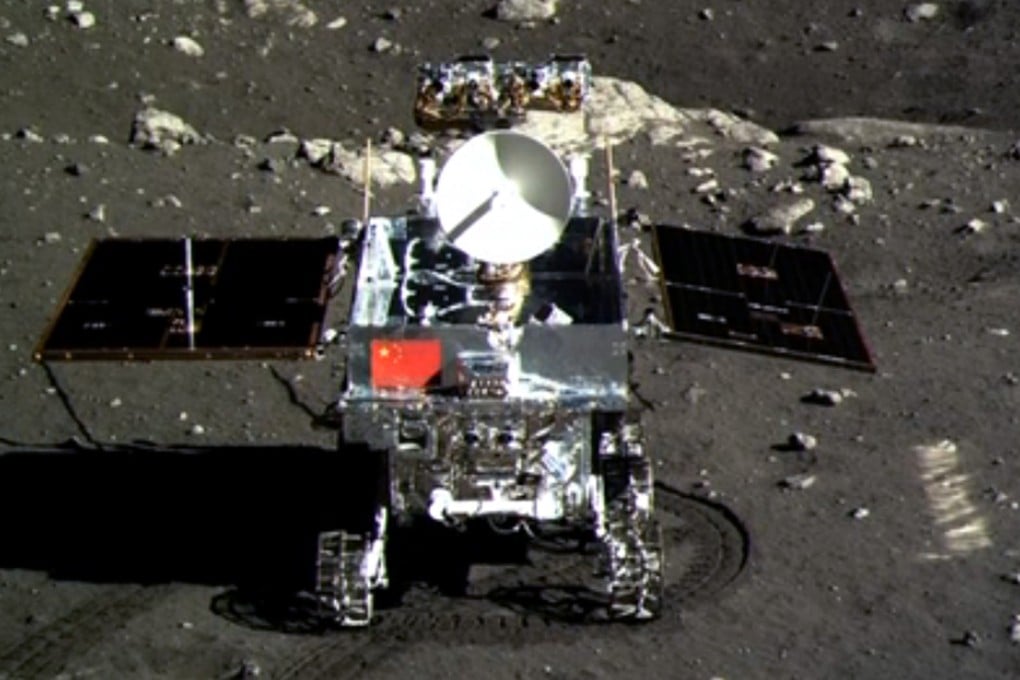

Forty-five years later, headlines across the world are now predicting that the next man to set foot on the moon will be Chinese. Last month, an unmanned spacecraft from China became the first vehicle in 37 years to make a soft landing on the moon; and no man has set foot on the lunar surface since December 1972.

Over half a century of space exploration has confirmed the close symbiotic relationship between politics, science and the exercise of what is today known as "soft power". Nothing projects a nation's prestige and prowess like its ability to marshal resources and launch men and machines into the cosmos.

Just as the Chinese people celebrate their space programme's achievement as a demonstration of the country's growing technological, scientific and economic strength, the Apollo 8 mission of 1968 epitomised both the cold war and the "white heat" of the 1960s. What became known as the "space race" between the US and the Soviet Union began on May 25, 1961, when president John F. Kennedy announced America's commitment to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. Such brazenness was typical of the ambition of the early 1960s.

But Kennedy's aspirations were also the product of cold war politics: in 1957, the US had been embarrassed by Moscow's launch of Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the earth, and the humiliation was amplified when Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the earth in 1961. Kennedy needed something to convince the world, but more importantly Americans, that US power and prestige were not diminishing.

Without Apollo 8's success in 1968 it is unlikely that Apollo 11 would have taken man to the moon and back; and without the political motivation of the cold war, it is unlikely that space exploration would have occurred at such a gallop.