China must rally its people to win the war against terrorism

Zhou Zunyou says the Chinese government cannot win the fight against terrorism unless it rallies its people to the cause. To do this, it must be prepared to be more open with information

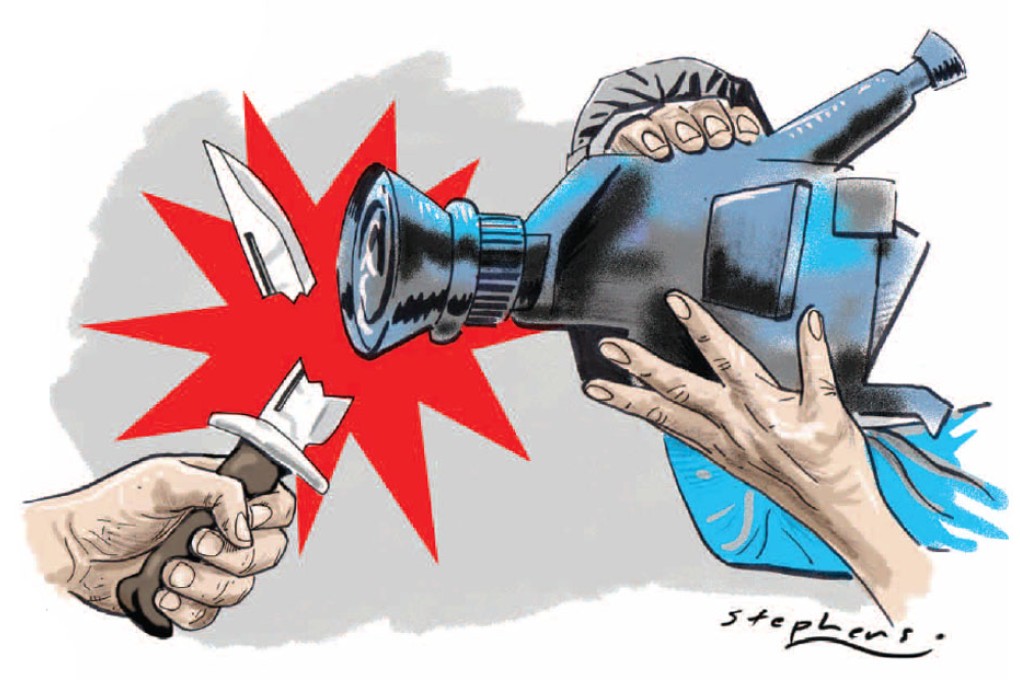

China appears to be plagued by terrorism. Tuesday's knife assault at Guangzhou Railway Station was only the latest in a spate of violence that has left many Chinese shaken.

Six people were injured in the assault, which came within a week of a major attack in Urumqi last Wednesday in which three people were killed, including the two suspects, and 79 others wounded. The two suspects in the Urumqi attack, who it was claimed had been involved in religious extremism for a long time, wielded knives and detonated bombs at the South Railway Station in the Xinjiang capital.

The attack happened just hours after President Xi Jinping concluded a four-day inspection tour of the region, a trip supposedly designed to promote the government's efforts to fight terrorism.

The Urumqi bombing was the third major terrorist act in China in six months. Last October, a jeep crash and explosion in Beijing killed five people, including the three attackers in the vehicle, and injured some 40 others. In March, knife-wielding assailants went on a rampage at a Kunming railway station that left 29 people dead and some 140 others injured.

All three deadly attacks had similar characteristics. Worryingly, the frequency and intensity of the violence in the past few months suggest an unsettling escalation of terrorist activities.

For the time being, the militants only seem able to deploy fairly crude weapons, such as long knives and home-made explosives. It would be a nightmare for Chinese leaders if these terrorists could one day get their hands on weapons of mass destruction, including the most dangerous weapons like nuclear ones.