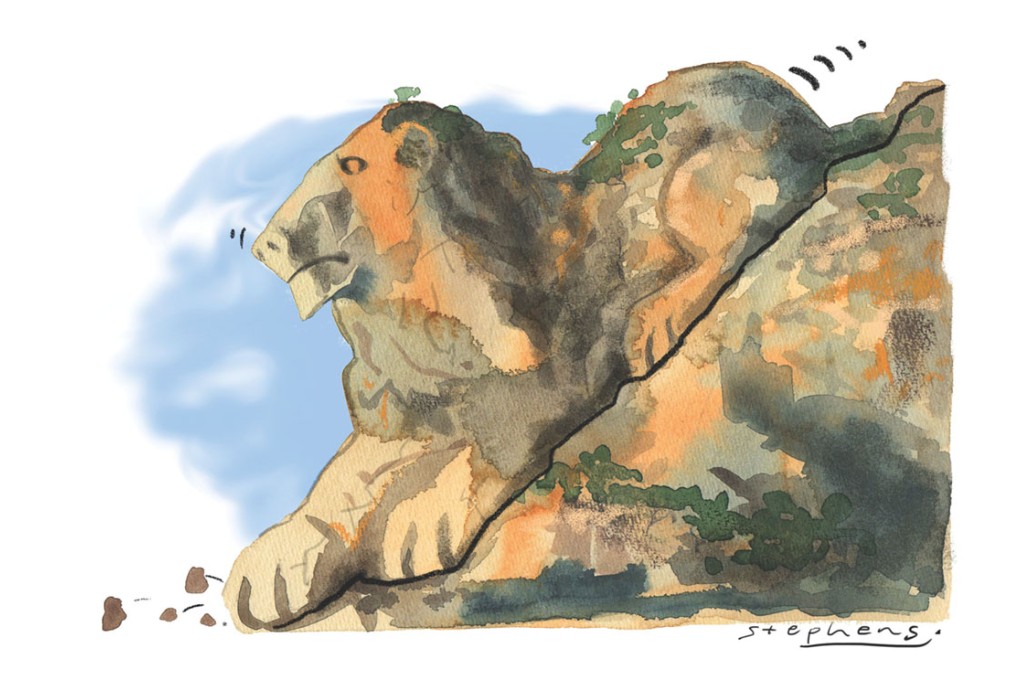

In search of this generation's Lion Rock spirit

Larry Au says if we are to agree on the right policies and direction for our society, in a time of dispiriting division, we must first seek some answers to what being a Hongkonger means

Of the seven students from Hong Kong who graduated from Brown University, my alma mater, in May, only one will be returning to the city for full-time employment after this summer. For the most part, the rest will either be in New York or San Francisco.

As a recent college graduate who has spent the better part of my adult years abroad, the choice of whether to return to Hong Kong is one that many my age with similar experience face. According to government statistics released in 2011, there were some 75,000 students overseas. While concerns about job opportunities and the cost of living feature prominently in conversations with my peers, we often return to the question of whether we can still call Hong Kong home.

But what does it mean to belong in Hong Kong? This, it seems, is a conversation that we as a community have yet to have. Only in recent years, as we confronted the right of abode controversies and argued over the anti-national education movement, have we begun to realise the limits and contradictions of our understanding of belonging.

These moments, however, are reactive. In other words, we can only say what being part of Hong Kong is not, but not what it is.

Paradoxically, this failure to substantively define "Hongkongness" occurs in spite of the recent rise of "nativist" movements and the record-breaking levels of local identification as reported by the University of Hong Kong's public opinion programme.

In contrast, any Frenchman or American will be able to tell you what being a member of French or American society entails. Their answers will be coloured by culture and history, of course. To be French is to embrace liberté, égalité, fraternité, while being American is to relish life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.