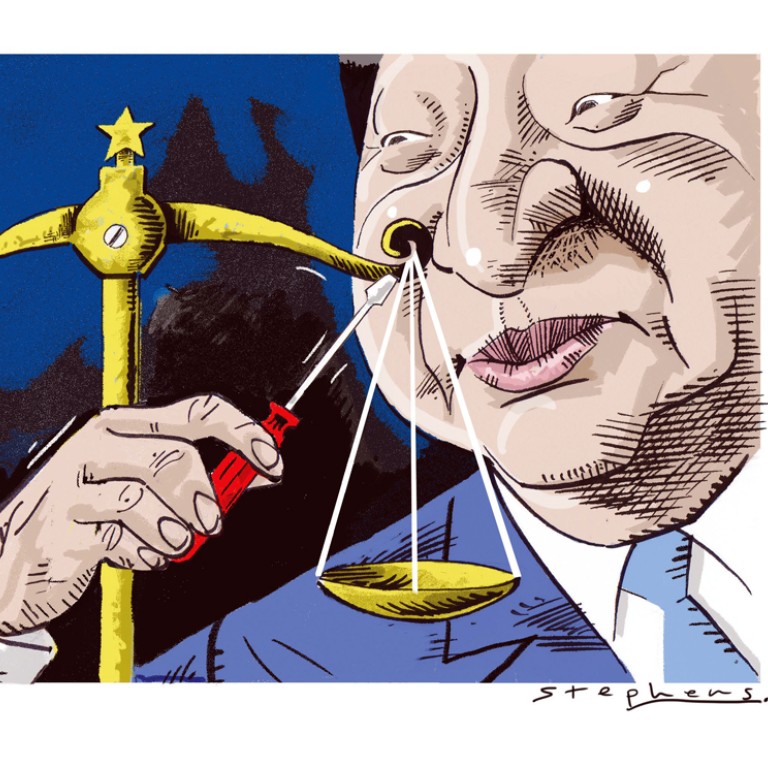

China's socialist rule of law still offers real hope of improvements to legal system

Jerome A. Cohen says while Xi is building on the Communist heritage of using the law as the ultimate expression of power, the reforms signal important advances in the legal system

Over 50 years ago, when I began to study the roles of law in Chinese life, some American China specialists thought I had chosen the one subject that the "central realm" had never regarded as important. I wonder what they would make of the just-concluded Central Committee plenary session that, for the first time in its long series of annual meetings, focused the attention of the Communist Party, the people and the world on "ruling the country according to law" and "the rule of law".

For the past fortnight, observers have been striving to decipher the documents issued by the fourth plenum of the 18th party congress. First came the lengthy and mind-numbing communiqué that endorsed a laundry list of often conflicting changes in the legal system that reformers of one type or another had previously recommended. Several days later came the plenum's decision. It had been expected to give more concrete and consistent definitions to the many ambitions articulated among the communiqué's ideological platitudes and legal clichés. Yet, with a few exceptions, it proved disappointingly vague. Fortunately, the decision was accompanied by an "explanation" delivered by party General Secretary Xi Jinping that, while hardly free of sleep-inducing jargon, nevertheless promoted understanding of how the decision had developed and the ideas underlying its organisation and objectives.

Analysts have already spilled a huge amount of ink parsing these documents. Drawn to the many references to "rule of law", in the sense of placing the government and the party, as well as everyone else, under the restraints of the constitution and legislation, at least one foreign commentator speculated that this might be a historical turning point, the equivalent in China's millennial authoritarian tradition of King John's reluctant grant of the Magna Carta to English nobles. Others, properly noting the even more prominent and contradictory emphasis on strengthening the party's existing monopolisation of the legal system, branded "socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics" a political oxymoron. Some Chinese human rights lawyers, who have taken temporary refuge abroad from the regime's ever greater repression, simply dismissed the fourth plenum as worthless sophistry.

These documents offer a kind of Rorschach test in which the viewer can find support for whatever is of interest or concern. There is something for everyone. To an American, their breadth, imprecise promises and inconsistent recommendations are reminiscent of the political platforms that Republicans and Democrats produce every four years to accompany the campaigns of their presidential candidates but that no one takes very seriously.

Yet we should take seriously the core rhetoric and pledges of the Central Committee, for they may initiate important, if limited and surely not historic, improvements in China's legal system. Such changes can stimulate greater respect for and compliance with the law, particularly at lower levels of government, where that has been sadly lacking. Years ago, a shrewd Chinese friend warned me about the importance of distinguishing between central government theory and local government practice. He recited a well-known couplet that I translate as: "High-level officials put us at ease. Low-level officials do as they please."

The fourth plenum represents the new Chinese leadership's Promethean effort to alter this situation by advocating a vast range of measures to improve the practice, fairness, reputation and legitimacy of the legal system, especially China's roughly 3,000 local courts and 3,000 prosecutors' offices. Of course, the party's most powerful leaders do not want to subject their own decisions to the strictures of law, as their continuing illegal confinement of their former colleague Zhou Yongkang demonstrates daily. Yet they plainly want to end the local protectionism, politics, corruption, backdoor contacts and other adverse influences that distort mundane judicial decision-making, fuelling popular distrust of the courts and the entire legal system.

Xi's reliance on law should not come as a surprise. It is orthodox communism. One of the fundamental tenets of Marxism is that law is the tool of the ruling class. Lenin, a disappointed trial lawyer before turning successful revolutionary, saw law as an essential instrument for establishing nationwide power. Stalin, at the very height of his lawless Moscow purge trials, nevertheless preached: "We need the stability of the laws now more than ever."

When, following the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping and comrades announced - in December 1978 at the third plenary session of the 11th party Central Committee - the transformative policy of reform and opening up, they made it clear that at least a Soviet-style legal system would be indispensable. Without law, there would be no way to re-establish functioning government throughout the country. Law would be a prerequisite to China's domestic economic development. It would also be necessary for attracting foreign trade, technology transfer and direct investment and for settling the millions of civil, economic, administrative and criminal disputes that plague every society. In addition, the legal system would have to not only effectively suppress crime but also protect the basic rights of the person that had been so badly abused in the first three decades of the People's Republic.

Thus, Xi is building on his Communist heritage as well on as China's imperial tradition of using law as the pre-eminent expression of central power.

Unfortunately, the vision of "ruling according to law" and "rule of law" that Xi has distilled from these historic influences is similar to that of Chiang Kai-shek, another practitioner of Leninist government, who presided over the economic development of pre-democratic Taiwan after losing the Nationalist Party's control of mainland China in the 1940s' civil war.

In practice, Xi, like Chiang, has ruthlessly repressed human rights lawyers and their clients, which is why the fourth plenum promises no relief to criminal defence and public interest lawyers and actually threatens to worsen their plight. But that, like other topics discussed in these new documents, will be the subject of future analysis.