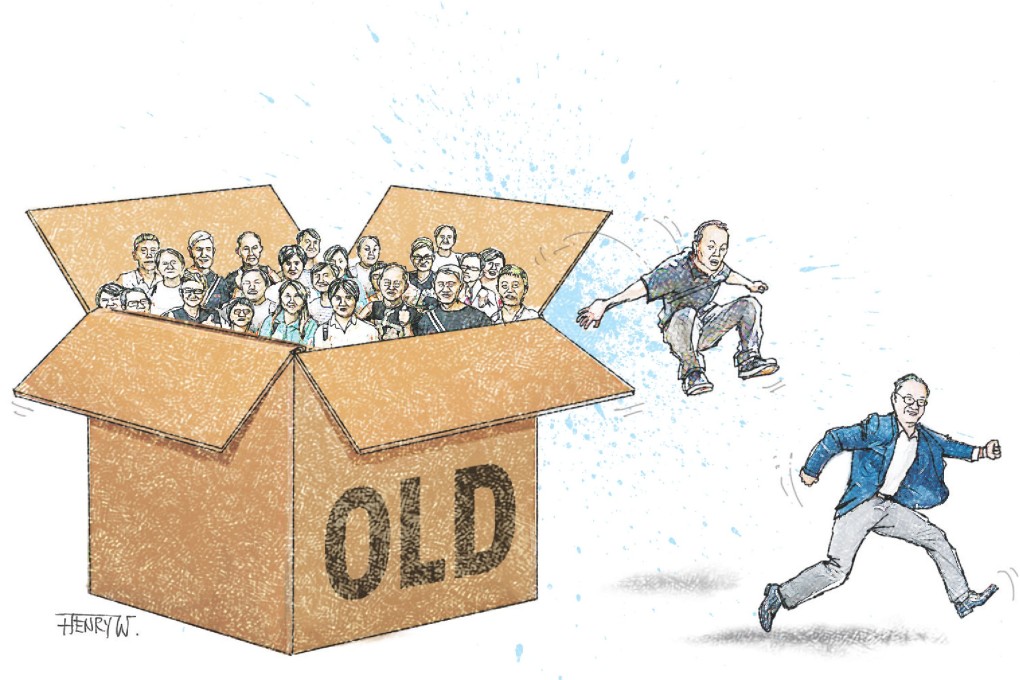

Old at 65? Not in the 21st century

Paul Yip and Stuart Basten say our definition of old age, now set at 65, should change as our life expectancies increase and general health improves, to better reflect our dependency ratio

Like other places in East Asia, Hong Kong's low fertility rates and improved life expectancy mean it is facing the challenges of a rapidly ageing society. From 2018, its working-age population is forecast to start to decline despite an increase in total population.

Demographers base such claims on what's known as the old-age dependency ratio, a measurement that compares the number of people aged 65 and above with those of working age - usually between 20 and 64. In Hong Kong's case, in 1970, for every 100 people aged 20-64, there were just 8.2 aged 65 and over. That figure is currently around 18.7.

This is the second-highest in Asia, after Japan. According to the latest UN forecasts, this is set to double by 2025 to 36.7, rising to 67 by mid-century - and these are under quite optimistic forecasts of an increase in birth rates, which is by no means guaranteed. Faced with these numbers, it is no surprise that population ageing is a frightening prospect for policymakers and business leaders in Hong Kong.

We should be more critical in the use of the old-age dependency ratio and think about how valid it really is. Firstly, it counts everyone aged 20-64 as part of the "labour force". Of course this is not the case, with many of those in this age group not being in full-time paid employment for a whole variety of reasons. At the same time, it assumes that everyone over the age of 65 is not in the labour force. But figures from the International Labour Organisation tell us that at least 10 per cent of men in Hong Kong are still actively engaged in paid employment.

The assumption that we become dependent at the age of 65 may have been a reasonable one to make in early 20th-century Europe, where industrialisation had taken root. At the time, many were indeed suffering ill health at 65 and life expectancy was much lower. Thus, they became "pensioners", dependent on financial and welfare support from the state and their former employers.

Now let us compare this situation with Hong Kong in the 21st century. Of course, the nature of our Mandatory Provident Fund system is different from Europe's pay-as-you-go pension system, and we have lower levels of support for the elderly.

But we should ask a fundamental question: Can citizens really be called "old" and "dependent" once they turn 65? The evidence suggests that this man-made boundary for old age may not be suitable for use in the future.