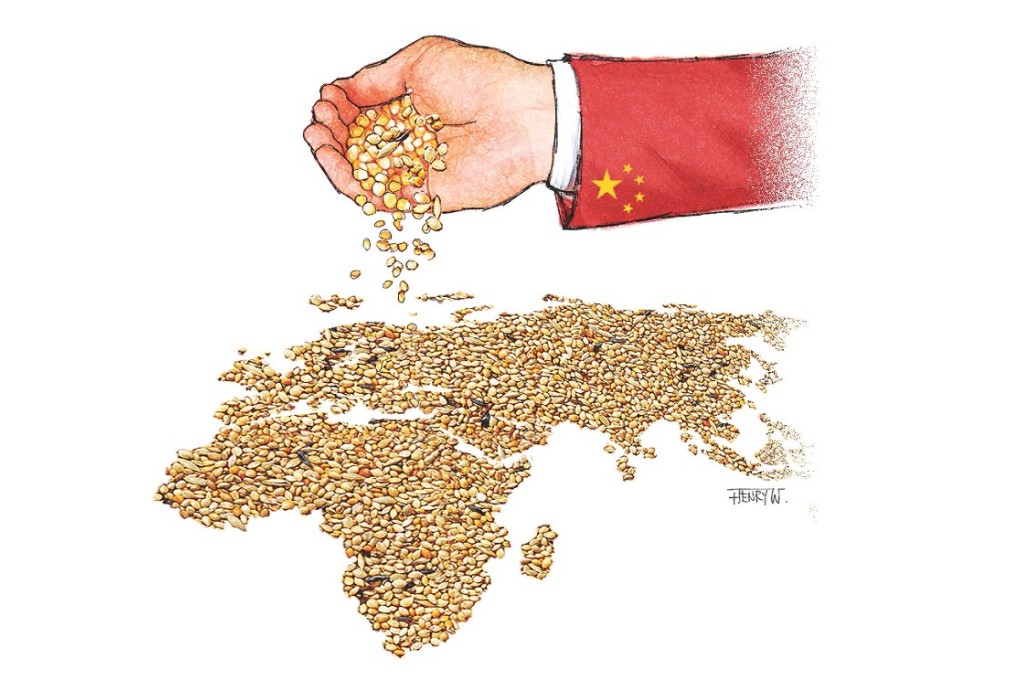

In seeking to feed itself, China can make sure others are well fed too

Loro Horta says while China has little choice but to seek farmland abroad to meet its growing demand for food, it must be open about these ventures and ensure the host nations benefit

China is the world's second-largest economy, but, ironically, food security is now emerging as one of the main concerns for its communist leaders. During a visit to an Argentinian farm in July, President Xi Jinping said: "If China is going to grow, it must solve its grain problem for its 1.3 billion population first." Measures taken by China to address the problem - going to the world - may not be a panacea.

As China grows wealthier, food consumption and diet have undergone a dramatic transformation. Between 1980 and 2005, meat consumption quadrupled, reaching 59.5kg per person a year, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation. Meat consumption is likely to continue to increase in the coming years as more Chinese join the ranks of the expanding middle class. Chinese are also developing a voracious appetite for certain delicacies taken for granted in the West such as coffee, spices, vegetables such as asparagus and exotic fruits like avocados and blueberries.

China is home to 22 per cent of the world's population, but possesses around 7 per cent of its arable land. However, in recent years, this arable land has been shrinking as a result of serious environmental damage such as soil erosion, deforestation and pollution of rivers and lakes. Last month, officials reported that more than 40 per cent of China's arable land is suffering from degradation.

The combination of increasing food demand and reduced arable land will make it difficult for China to feed itself in the not-so-distant future. In the past decade, China has experienced hikes in food prices and shortages of certain products.

China has no choice but to turn to overseas farming. In 2013, it imported 4 per cent of the world's grain and this is likely to rise. In recent years, Chinese investment in overseas agriculture and land leases has steadily increased. Chinese companies began investing in neighbouring Laos and Cambodia farmland in the early 2000s and slowly ventured further afield. Chinese-owned or jointly owned farms are now in several African countries, including Mozambique and Ethiopia.

In Mozambique, a Hubei-based company has invested US$250 million in a rice farm in Gaza province. In November last year, a director at the country's ministry of agriculture was reported to have said that several Chinese conglomerates were expected to invest up to US$2.5 billion in its agricultural sector.

In Angola, Chinese state-owned giant Citic pledged to invest US$5 billion in agriculture in addition to its current lease of 20,000 hectares of land. Mozambique and Angola in particular are large countries with immense tracts of fertile land and a small population.