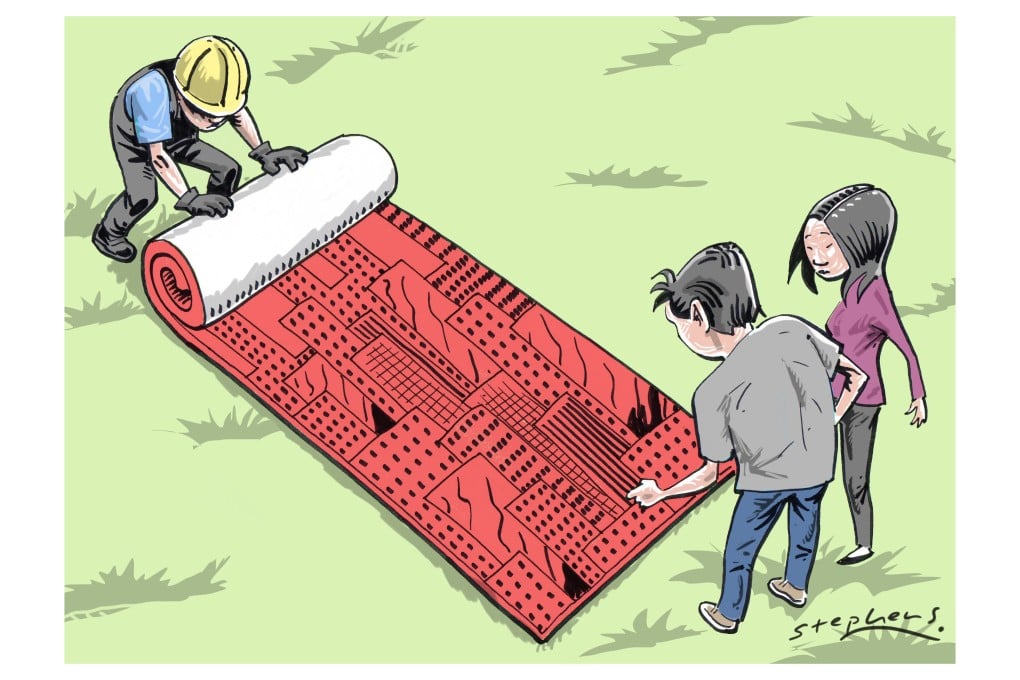

For China's city planners, people-centred growth is no urban myth

Winston Mok says China's latest urbanisation plan shows a balance of focus across different regions - and it's up to each pilot zone to turn it into growth that truly answers people's needs

While the three new free trade zones have captured a lot of attention of late, a broader experiment is unfolding with potentially far greater impact.

Beijing has just designated 64 pilot zones - ranging from provinces to districts - for urbanisation. From the selection of these zones, it's possible to glimpse the probable pattern of China's future urban development.

First, the coastal region will continue to be a key driver for urbanisation. Cities like Dalian , Qingdao and Ningbo are on the list while Jiangsu , with the second-largest economy after Guangdong, is one of two provinces selected. The large city of Suzhou has become a magnet for migrant workers.

Besides its large cities, Jiangsu also has some of the strongest small, county-level cities in China. That makes it capable of integrating people - from both inside and outside the province. Already the most urbanised region of China, the coastal area will go from strength to strength.

Second, the Yangtze economic belt - a key development priority for Beijing - will be a vital new engine for China's urbanisation. The belt cities of Wuhan , Changsha and Chongqing are on the list. Anhui is the other province designated as a pilot zone.

China's most important cities away from the coast are on the belt, and with recent economic development inland, many migrant workers have been returning home.