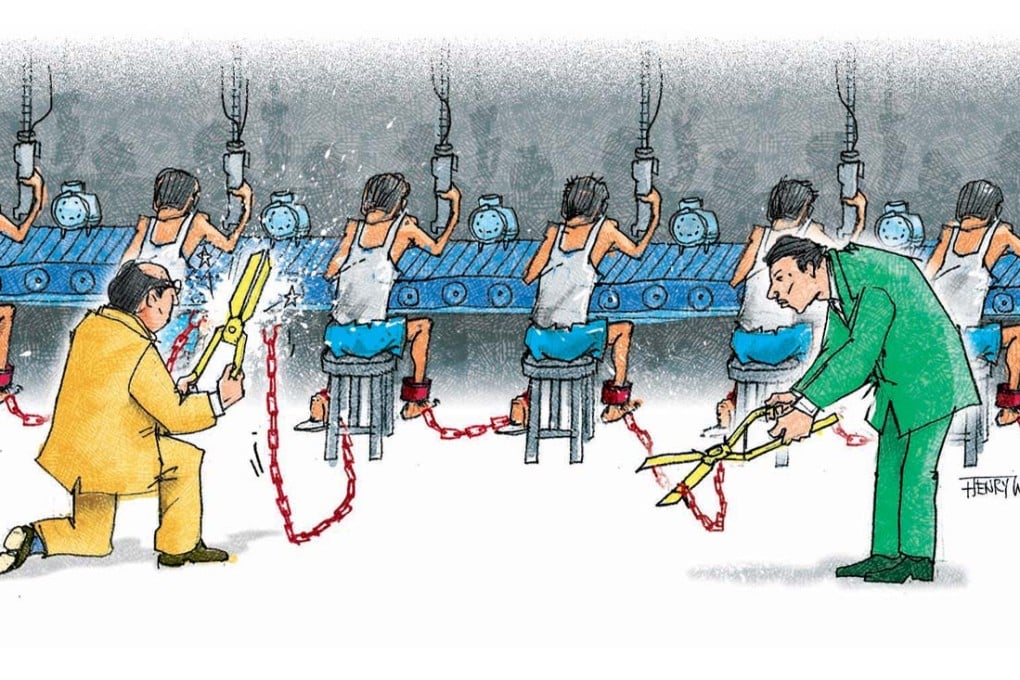

Companies should do more to clean up the dirty business of forced labour

Matt Friedman says all legitimate businesses have a responsibility to root out slave labour, not only because it is a crime and morally offensive, but also because it affects corporate credibility

About every 15 seconds, a man, woman or child is forced into slavery. In our advanced, sophisticated societies, how disheartening and downright shocking it is to hear of factory workers who are paid nothing, toiling away in dangerous medieval slavery conditions, to produce the skinny jeans and hoodies we wear.

Even more unacceptable is that, according to the Global Slavery Index, there are 35 million women, men and children all over the world - with more than half in Asia - who are forced into slave labour or sexual slavery. These victims, who can be found in factories, on construction sites, within fisheries and sex venues, are forced to work for little or no pay, deprived of their freedom and often subjected to unimaginable suffering.

Human trafficking or modern slavery, is a booming global business that shows no signs of abating. About 75 per cent of the 35 million people in slavery are in "forced labour" and, of this figure, about 60 per cent of the victims are associated with manufacturing supply chains, which begin with a grower or producer and end as a finished product purchased by consumers in the retail market. As consumers, we directly or indirectly contribute to this problem. According to the International Labour Organisation, the profits generated from this illicit trade exceed US$150 billion every year. With such lucrative returns, it's no surprise that the number of trafficked people continues to increase. By contrast, the annual global donor contributions given to tackle the problem add up to only US$350 million.

For more than a decade, the community of international non-profit organisations that fights human trafficking has not come close to meeting its full potential. While individual, small-scale success stories can be found, many victims are never identified, in part due to the hidden nature of this crime. For instance, the 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report, published by the US State Department, was able to account for only 46,000 victims receiving assistance globally. In the past few years, I have campaigned to raise awareness about modern slavery in Hong Kong, and have been involved in combating slavery at the UN and US Agency for International Development for over 25 years - before human trafficking was an official designation. In that time, I've come to the conclusion that businesses can play a critical role in fighting the bad business of modern slavery and eradicating this crime against humanity.

In the past, there was little incentive for private companies to care. It was considered too sensitive and something to be avoided at all costs. But, over time, we're seeing emerging trends that are drawing the private sector in.

First, with legislation in place in North America and Europe, it's expected that most corporate social responsibility declarations must address this topic.