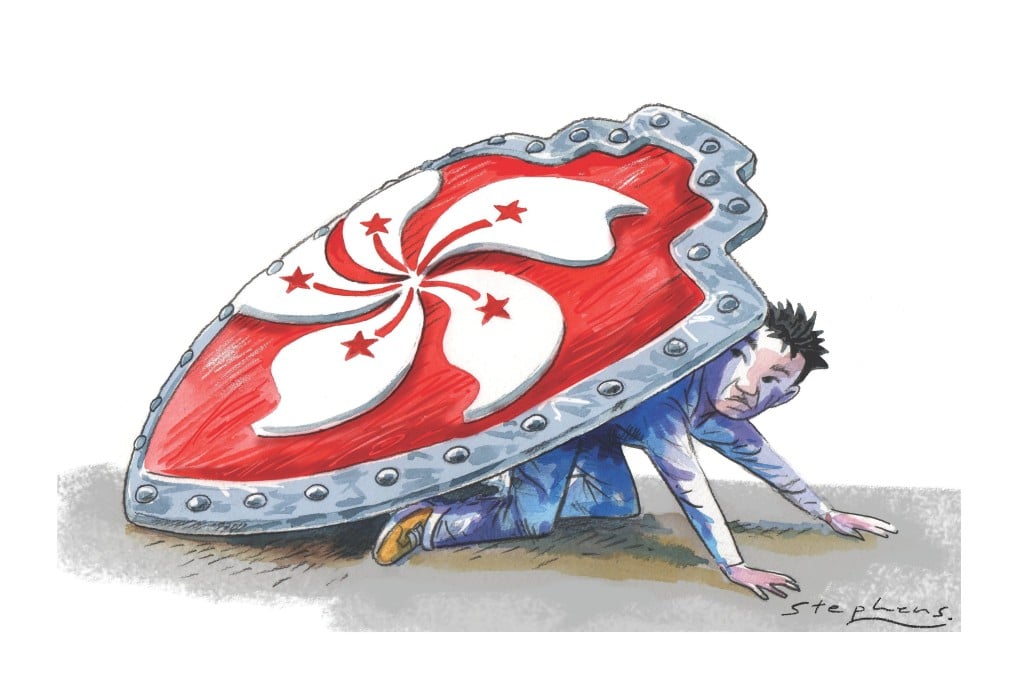

Until society trusts the authorities, there can be no national security legislation in Hong Kong

Wilson Leung says authorities need to regain the public's confidence before seeking to enact national security laws, and the best way to do that would be to fulfil their promise of universal suffrage

In the film Groundhog Day, Bill Murray's character is stuck in a time loop, forced to relive the same day again and again. It is only when he realises the error of his egocentric ways and develops compassion for mankind that he is able to break out of the loop and carry on with his life (alongside a newfound love).

Hong Kong people may be forgiven for thinking they are stuck in the same kind of time loop. In 2003, the government was proposing to enact national security legislation in order to implement Article 23 of the Basic Law. The push was spearheaded by Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, a rising star in the establishment. Another prominent proponent was chief executive Tung Chee-hwa. The rest of the story is well known: following a massive protest on July 1, the bill was shelved, Ip resigned, and Tung departed not long after.

Twelve years later, we hear noises again about national security legislation and Article 23. Tung, having apparently recovered from the leg pains that afflicted him at the time of his resignation, is again trotting out - or being trotted out - to remind Hongkongers of the importance and desirability of national security. Ip's political star is back in the ascendancy, and she, along with Antony Leung - another throwback to 2003 - are being touted as possible contenders for the city's top job. Will Hong Kong, like Murray's character, be able to break free and live happily ever after?

Both in 2003 and now, we are constantly reminded by the Article 23 cheering squad that Hong Kong has a constitutional obligation under the Basic Law to enact national security legislation. However, there are two essential points that are being ignored by these enthusiasts.

First, the Basic Law does not stipulate a time limit for the enactment of the legislation. This clearly means that it is left to Hong Kong to enact the legislation at an appropriate time of its own choosing. What constitutes an appropriate time depends on the political, social and economic conditions prevailing in the city.

Second, Hong Kong equally has a constitutional obligation to implement elections for the chief executive by universal suffrage. This obligation exists because of Article 45, read together with the National People's Congress Standing Committee's decision of August 31, that there is a need for selecting the chief executive through universal suffrage for 2017 and after.