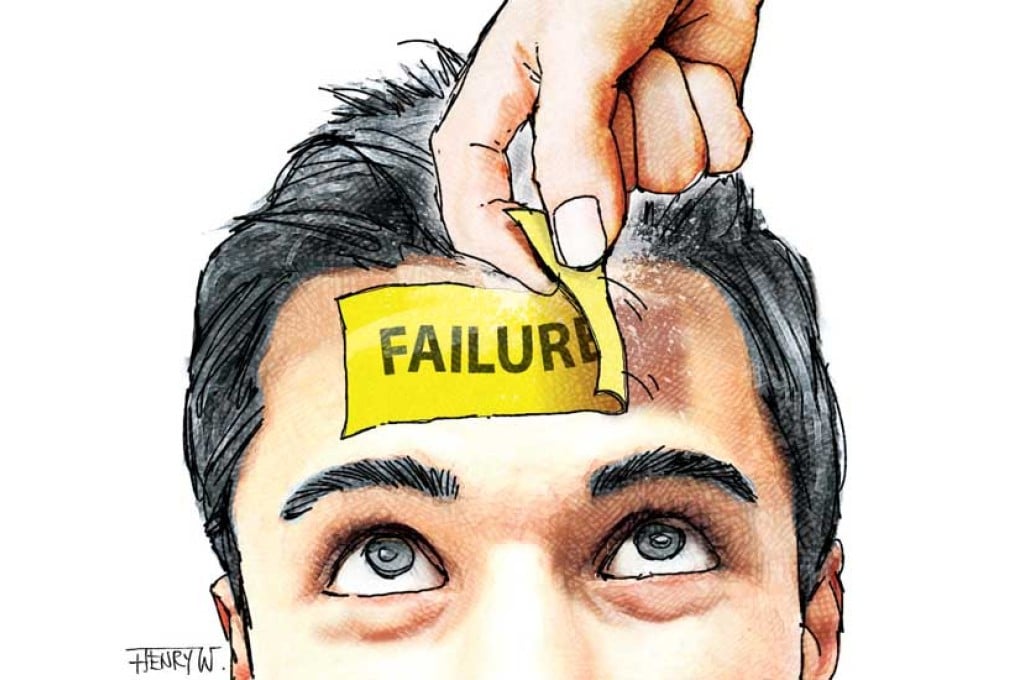

Fear of failure holds back entrepreneurs in Hong Kong

Douglas Young calls for a rethink of success that recognises the usefulness of failure. By accepting it, he says, Hong Kong may bolster its entrepreneurship with a new spirit of daring

The media was quick to hail the Heritage Foundation's naming of Hong Kong as the world's freest economy for the 21st year running. But it didn't take long for critics to begin to question the true significance of the honour.

To paraphrase George Orwell: the business environment may be free, but some businesses are more free than others.

With few constraints on monopolies, conglomerates are free to dominate the market, while an artificially limited supply of land means developers are free to manipulate supply and demand.

And, a lack of protection for small local businesses means multinationals are free to come in and squeeze out family set-ups.

It is not a new phenomenon that neighbourhoods once served by individual shops are being taken over by large local chains. With the world's attention on mainland Chinese consumers, what is more worrying is the arrival of international giants in Hong Kong to establish beachheads.

They are able to offer landlords higher rents than local operators can afford because they can balance short-term losses with a long-term goal to conquer the mainland market. Setting up in Hong Kong is seen as an investment in establishing brand prestige. The short-term losses here will pale in comparison to the real profits that are to be made on eventual mainland expansion.