The stigma of chronic illness in Hong Kong

York Chow says misunderstandings about medical disorders such as epilepsy and other, rarer conditions result in discrimination and inadequate support that add to patients' misery

The last day of February is designated by the World Health Organisation as Rare Disease Day, aimed at raising public awareness on a wide range of rare diseases and the impact on the lives of those living with them. Meanwhile, here in Hong Kong, we observe March as Epilepsy Awareness Month. Together, they give us an opportune moment to assess our own progress on addressing the barriers to equal opportunities faced by those living with chronic medical conditions.

Of course, epilepsy is not rare. One in every hundred people worldwide, including in Hong Kong, will have an epileptic seizure at some point in their lives. But for people living with epilepsy, other less-known neurological disorders as well as rare diseases, the challenges they continue to face remain similar and far too common. These include a lack of general awareness and understanding about their medical conditions, as well as discriminatory attitudes and stereotypical views about them.

It is time for us, as a society, to break down the barriers of stigma and offer support. At the moment, despite medical advances which enable many people with chronic conditions to live regular lives, poor attitudes and a lack of understanding remain a major disabling factor. For instance, it was less than five years ago that the term for epilepsy was renamed in Cantonese, to remove the negative connotation of madness that had been attached to this neurological condition.

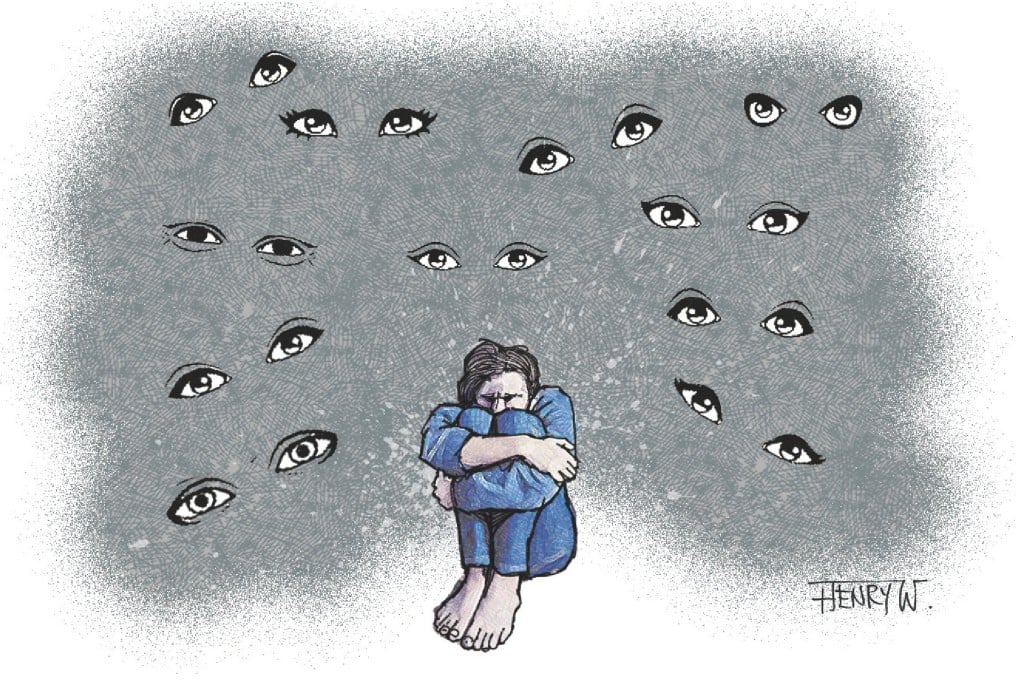

Stigma can have a devastating impact both on a patient's willingness to seek, as well as on their ability to access, timely diagnosis and necessary treatment. It also means that many people living with chronic conditions regularly face social rejection. They have difficulties finding work, or they often lose their jobs because of their conditions. They are also more likely to be ostracised or bullied in school.

Indeed, it is not surprising that even though conditions such as epilepsy are more common than most people realise, many of those who suffer from it may prefer to remain silent, fearful of bias and mistreatment. And the impact has many reverberations, affecting not only the patients, but also their family and carers.

The lack of awareness about such groups also feeds into the corresponding lack of much-needed assistance and resources. For example, Hong Kong does not have an official definition of what a "rare disease" is, which leads to insufficient, targeted support. To date, according to the Hong Kong Alliance for Rare Diseases, over 6,000 types of rare diseases have been identified globally. In Hong Kong, although the Hospital Authority's Expert Panel on Rare Metabolic Diseases was set up in 2007, only patients with six types of rare metabolic diseases can access the support of the government, including funding on drugs and other forms of therapy. Many others with rare diseases continue to face limited treatment options and a high financial burden.

The hurdles are not undefeatable. We need to work together to heighten awareness and address this gap in existing services and support measures.