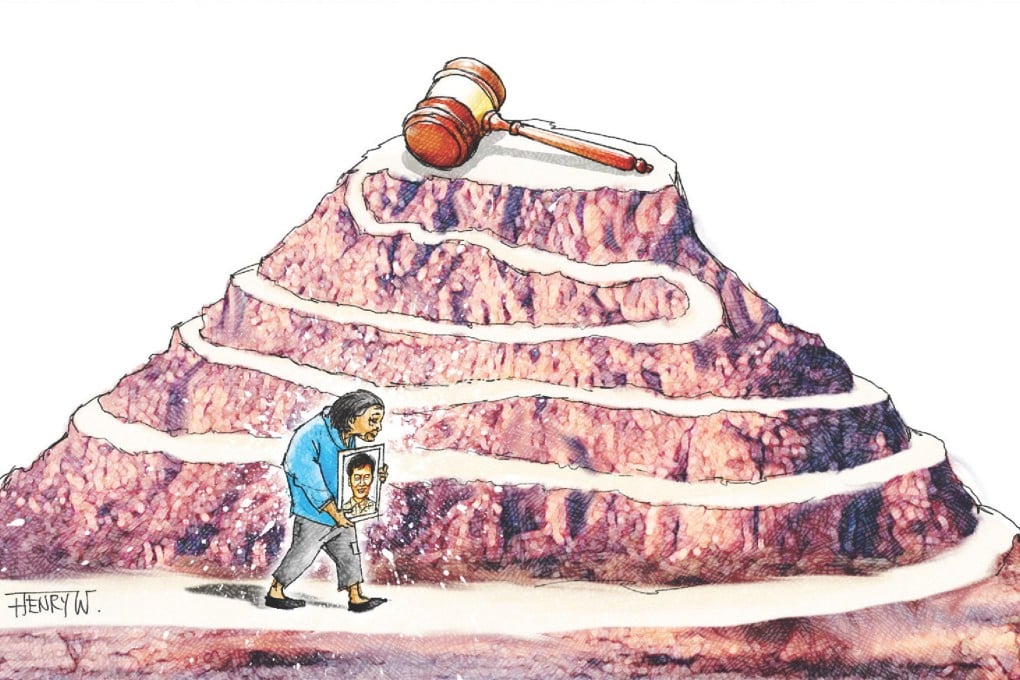

For still too many, the road to justice is long in China

Grenville Cross says the arrival of new mainland legal safeguards is an important development for rule of law, but implementation is essential if further miscarriages of justice are to be avoided

In 1995, Nie Shubin, a farmer aged 21, was executed for the rape and murder of Kang Juhua, a woman in her thirties, in Hebei province. In 2005, however, a man called Wang Shujin, who was wanted in connection with three other rape-murder cases, confessed to the offences and described the crime scene to the police in detail. Nie had allegedly been tortured into confessing to the crimes, and his mother, Zhang Huanzhi, who said her son's death had "destroyed my future", has campaigned ceaselessly to clear his name.

However, the Hebei High Court, which approved the death penalty in Nie's case, rejected Wang's confession to the murder, and Nie's convictions stand. The Hebei authorities, moreover, refused over 50 requests from Zhang's lawyers to examine the complete case papers, allowing only one request, in 2013. Even then, the lawyers were only allowed to see 26 pages out of 137, which were carefully selected to prove Nie's guilt.

Last December, however, the Supreme People's Court intervened and transferred the case from Hebei to the Shandong High Court, which granted the family access not only to Nie's case files but also to Wang's. One of Zhang's lawyers, Li Shuting, concluded that "the case is 100 per cent a wrongful execution", and there are now high hopes that Nie's convictions will be overturned.

The mainland authorities have recently tightened the safeguards for suspects in criminal cases, partly in response to miscarriages of justice, but also to raise criminal justice standards to international norms.

In March 2012, the National People's Congress approved amendments to the Criminal Procedure Law designed to prevent the use by trial courts of illegally obtained evidence. In particular, coerced confessions are not now admissible against a suspect, and evidence obtained by illegal means must be excluded at trial.

Although this was a positive step, there is an onus on an accused to provide evidence that he was tortured, and instances of forced confessions being excluded at trial are hard to come by. An additional problem has been the willingness of the courts to accept undertakings by the police that they have not engaged in improper questioning of suspects, even where there has been lengthy interviewing in oppressive circumstances.

Investigators, moreover, have sometimes been able to exploit legal ambiguities to get around the new requirements, and it remains to be seen if the Ministry of Public Security, which supervises the police, will fully throw its weight behind the reforms. To its credit, however, the ministry has recently issued a directive proscribing "coerced confessions and torture", and this, hopefully, is more than mere window dressing.