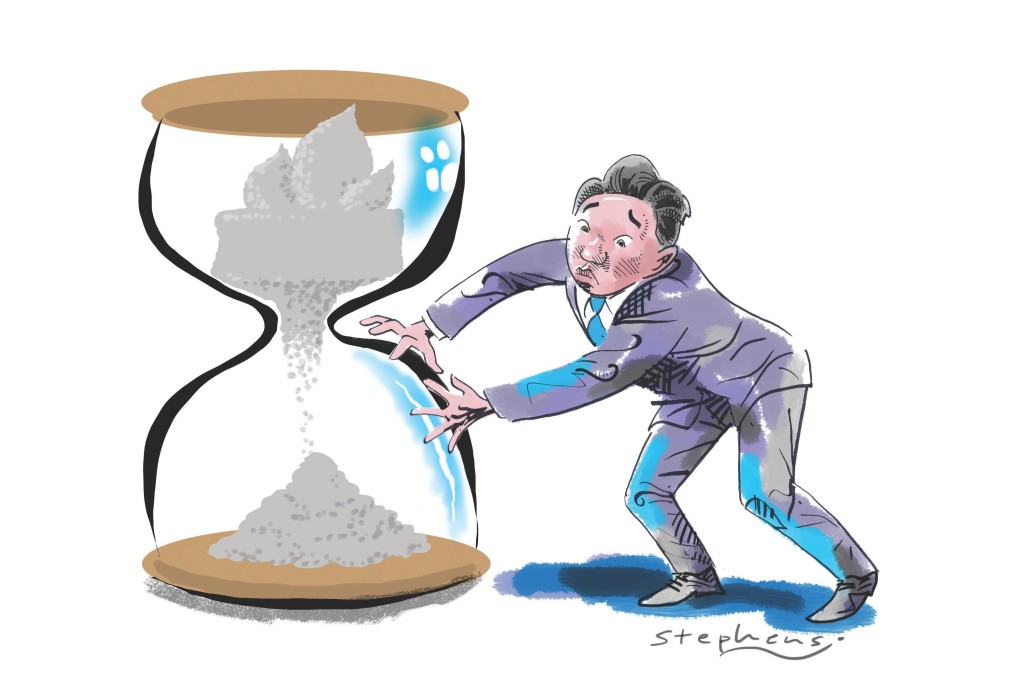

Time is not on the side of Hong Kong's democracy campaigners

Johnny Mok says given just 50 years of autonomy to experiment with its system of governance, Hong Kong must not squander the chance to reach a compromise on the 2017 election

Not long ago, a rain-drenched Singapore turned out en masse to bid farewell to its founding father Lee Kuan Yew. The state funeral procession began from Parliament House fronting the Padang, the very spot where, on August 9, 1965, thousands had come to witness Lee's proclamation of Singapore's independence. Almost 50 years have lapsed since that date. The outpouring of tributes paid to him by leaders from around the world, the raw emotions that have engulfed the city, and all the international indices which objectively verified the leaps and bounds of the country's progress over this half-century period, all bear testimony to Lee's phenomenal achievement for the once slum-infested backwater town of Southeast Asia. Some have called it miraculous.

The "Singapore Model" that Lee Kuan Yew built has been succinctly described as "a hybrid system of authoritarianism and democracy that vastly improved the well-being of his country's citizens". Critics have doubted whether this widely admired alternative to liberal democracy can ever be emulated successfully outside Singapore. Others have questioned the sustainability of the model in the absence of someone like Lee Kuan Yew, proposing that a more flexible and publicly accountable system would now work better to meet the changing demands of the people, especially in the area of dissent.

There is a sense that Singapore's stellar accomplishment is one of a kind, unique in its own time and place. Lee's legacy is firmly established, and a solid foundation laid for the country to evolve and hopefully outshine its past.

The Hong Kong special administrative region, likewise, has a unique model with no parallel anywhere else. It is defined in our Basic Law. This year is the 25th anniversary of its promulgation.

As with Singapore, Hong Kong also tops many economic indices, including being ranked the freest economy in the world for 21 years in a row.

On democratic developments, the Basic Law mandates the principle of "gradual and orderly progress". In this regard, we are now standing at a crossroads. The choice lies in whether we move ahead with the reform of the method of selecting the chief executive. The making of this choice will have profound consequences.

Under the Basic Law, "gradual and orderly progress" is translated into a specific formula so far as the election of chief executive is concerned. This is a model of consensus between three sides as set out in paragraph 7 of Annex 1; that is, a consensus between the Hong Kong SAR government (represented by the chief executive), the people of Hong Kong (represented by a two-thirds majority of Legislative Council members) and the central government (represented by the National People's Congress Standing Committee).