Asian writers struggle with the stereotype of their origins

Radhika Jha says their novels are expected to reflect personal experience

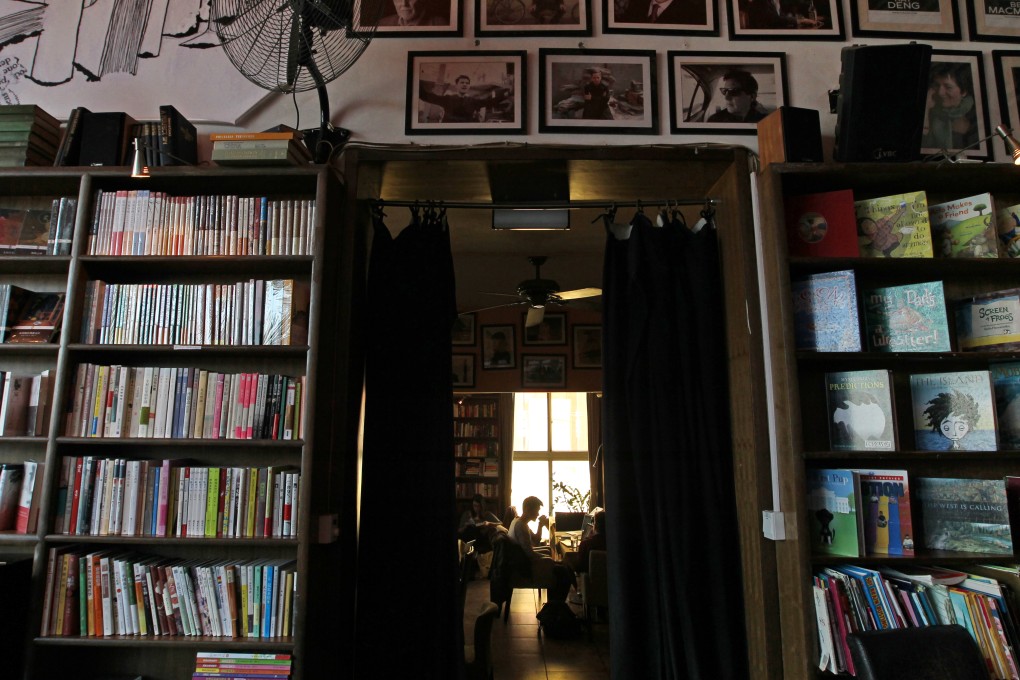

At the Beijing Bookworm Literary Festival, while browsing the bookstands, I heard a European woman comment wearily: "Asian writers are so predictable. Home, family, displacement and immigration - that's all they write about." Obnoxious as it was, there was a certain truth to the remark. For though one can find a plethora of novels written by Chinese, Bangladeshi, Lebanese, and other so-called non-native English speakers, the subjects they can write about have been limited by certain stereotypes about the writers themselves. While no one today doubts they can write in English, their words are not enough; it is their personal history and background, their apparently "authentic" knowledge of their culture of origin that gives their stories weight.

In his book, The Origins of Sex: A History of the First Sexual Revolution, historian Faramerz Dabhoiwala points out that though the 18th century was a time when people began to believe that sex was natural and hence good, paradoxically, the focus on human nature brought into being certain stereotypes about women's intrinsic nature (not enjoying or needing sex) and about homosexuality being "unnatural". These stereotypes about women and homosexuals made it impossible for them to enjoy the same sexual freedom that men enjoyed at the time.

Something similar has happened in the Anglophone literature world in the past 25 years. A mere 50 years ago, non-native English speakers were supposedly incapable of writing literature. Then, in the 1980s, a few non-native English speakers dared to write fiction, and because they were a rarity, they managed to write the kind of stories they wanted to. Barriers came down further all the way to the end of the 1990s.

Today, it is taken for granted that non-native speakers of English can write. But what they can write about must somehow be related to "personal experience". At book festivals, readers always want to know how much of a book is imagined and how much of it is "real". And while no editor will doubt the credibility of a novel about India written by a person of Indian origin or about Iraq written by an Iraqi-American, a novel about France, Italy or a third unrelated country by the same author, a novel that is "imagined" rather than experienced, will have far greater difficulty in getting published.

Immigrant stories and stories about displacement are also considered safe territory for the "non-native speaker". This is because, like in the 18th century, when there was a large-scale immigration of people from the country to cities like Paris and London, in the second half of the 20th century, there has been a wave of immigration from south to north. And so these "foreign" voices are thought to bring authenticity and a touch of spice to an experience that, through globalisation, is becoming more commonplace - the loss of home. At book festivals, when the writer has an exotic name, he/she is also often asked what he considers to be his/her home. And since many of these writers don't have one home but two, and don't really feel at home anywhere, the question never has a simple answer.

The writer who argued most successfully for the voice of personal experience was Mark Twain. He wrote that good writing could only come out of the seat of personal experience. Historian James Shapiro argues that Twain's point of view has come to dominate literature today and the idea that fiction is a work of the imagination has all but disappeared. While Shapiro may be overstating his case, it is very likely that a book like Siddhartha by Herman Hesse, about the life of the Buddha, would probably never get published today. The editors would immediately ask what the author's connections to Buddhism and India were and if he said he had none, they would probably laugh at him.