China should dangle some economic carrots for long-term success of war on corruption

Howard Chao says Beijing should perhaps look to Singapore, where paying top salaries keeps government clean

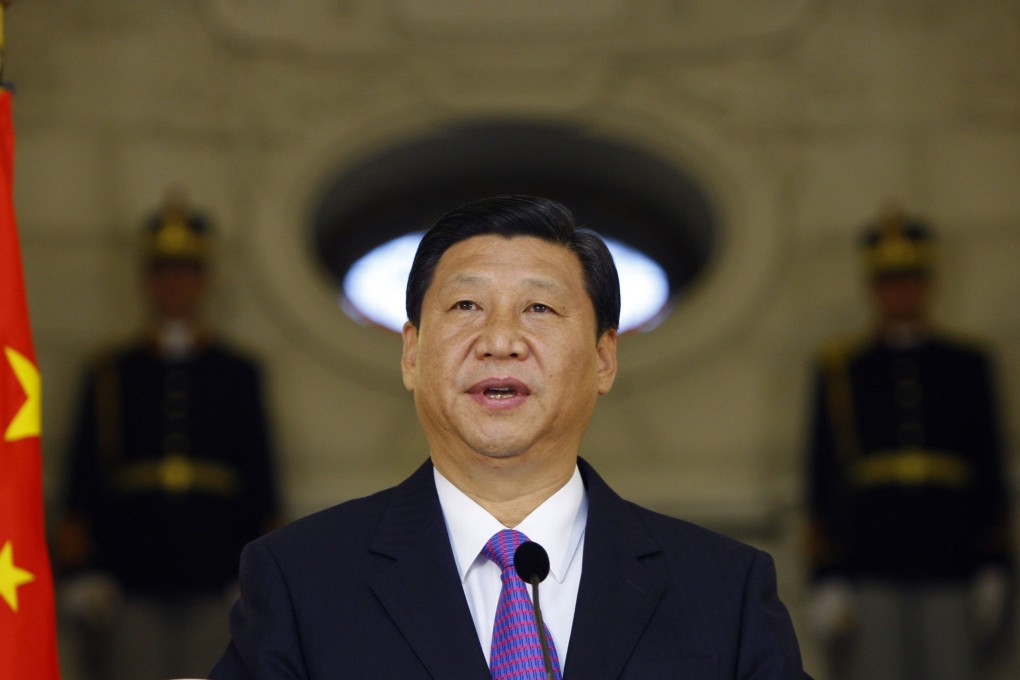

Even before President Xi Jinping took over, there was vigorous domestic and international agreement that something drastic needed to be done about China's corruption problem. His predecessor Hu Jintao warned in 2012 that it "could prove fatal to the party". Outside of China, pessimists pointed to corruption as a harbinger of the system's ultimate doom.

So the anti-corruption campaign is not surprising, and is receiving widespread support. Xi views it as a life and death struggle for the party and the nation - the most significant political rectification campaign since the Cultural Revolution.

The general buzz seems to be that Xi and his top graft-buster Wang Qishan have clean hands, and thus have the standing to lead the effort. There are many anecdotes about how both go to great lengths to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Based on the stature and numbers of political leaders they are taking on, it also appears they are willing to run significant personal risk to achieve their goals.

Cynics say the campaign is just a huge political power play cloaked in righteousness. While there is no question that many political opponents will be swept away, there are too many indications that it is about more than power. This regime did not need to antagonise so many high level "tigers" and such a broad swathe of "flies" merely to consolidate its grip.

While necessary, the campaign has raised serious concerns in the mainstream business community. Business has slowed because bureaucrats have become fearful about making mistakes and are thus reluctant to make important decisions. Business leaders are worried about instability within government as a result of internal struggles and the potential consequences for the economy. They wonder how long the campaign will last; all indications are it will last a long, long time.

The economic impact of the campaign has been significant. Business in Macau casinos, luxury goods, high-end restaurants and hotels, and fancy cars have all been hurt. Government and state-owned enterprise officials have become very discreet in their public profiles, and there have been many restrictions placed on their spending, perks and travel, making access difficult. Many officials are quietly trying to leave government and join the private sector. Capital flight has accelerated as those who have reason to be afraid, or are just afraid, have moved significant assets abroad, conveniently at a time when outbound investments are encouraged.