China and the US must get their strategic relationship right

David Lampton says China and the US must find common ground in strategic interests to avert conflict

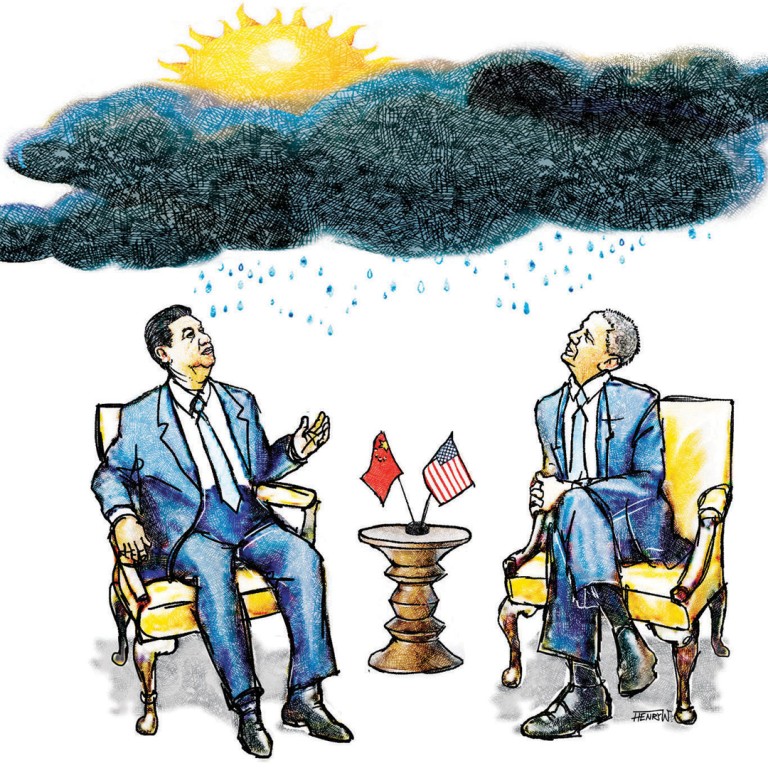

The heretofore positive balance between hope and fear in US-China relations is tipping in the direction of fears outweighing hopes. Righting this balance should be the objective of the imminent US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in Washington. More particularly, it needs to be the focus during President Xi Jinping's state visit to Washington in September.

The dialogue and summit need to focus on the strategic level, not just regurgitate a laundry list of grievances and trumpet success with small-bore "deliverables".

Ironically, while the economic and cultural dimensions of the bilateral relationship are deepening, at the most fundamental level - mutual security - the character of the relationship is deteriorating.

In both countries, the vocabulary of the relationship is rapidly shifting from one centred on "engagement" to one of "deterrence", with each seeing the other as a fundamental security problem. The US sees a challenge to the rules-based system it has endeavoured to build since the second world war and is disturbed by domestic tightening on the mainland. For its part, Beijing sees an ongoing challenge to its domestic legitimacy ("foreign subversion") and to China's resumption of a rightful place among the great powers. Mounting abrasions over US alliance relationships, the South China Sea and cybercrime are just a few examples of the zones of disquiet.

For almost 40 years, most Americans had perceived China to be "moving in the right direction" in terms of its global role and domestic circumstance, even if slowly and erratically. Chinese, too, generally saw America moving in a net constructive direction, being a society in which economic interests would, in the end, triumph over its containment and regime change impulses. Because each side saw the other as tolerably "moving in the right direction", the context in which decisions were made was one of playing the long game, being patient, and minimising friction while enlarging cooperation.

Yet, today, despite recent limited progress in areas like climate change, economic negotiations and military-to-military exchange, each nation's views of the other have become more negative. Each nation's policy towards the other is hardening, and every negative move by one party justifies the next ratcheting up by the other. Complicating things further, China sees itself as stronger, and therefore less in need of being patient.

Given this direction of development, what needs to be done?

To start with, what seemed the natural order of the postwar era when the US accounted for about 35 per cent of global gross domestic product is not sustainable when the share has fallen to below 20 per cent. Accommodating China's legitimate aspirations for a voice in the international system is essential. Resisting new institutions and redistributed influence will leave the US increasingly isolated and drained, as seen in the recent fiasco over the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Tangibly, this means moving ahead to adjust China's voting share in the International Monetary Fund.

Second, Deng Xiaoping's strategic lodestar was to minimise external conflict to focus internally. It was premised on China having enormous internal problems and limited strength, and wise in its recognition that if Beijing threw its weight around externally, it would create a bandwagon of nervous neighbours and distant powers that would coalesce against China.

Thus, if today's Beijing continues to create anxiety among neighbouring states, attack Western values, raise the spectre of foreign subversion and weaken China's interaction with Western foreign associations, as it would do if its draft laws on managing non-government organisations and national security are adopted in their present forms, it will encourage outsiders to draw closer together.

A need of the moment is for Beijing to improve relations with key neighbours and to take as many maritime disputes off the table as possible. In most of its past land disputes, China adopted an equitable pattern of settlement with neighbours, and it should do so now with respect to conflicting maritime claims. For its part, Washington should not be hung up over whether this is a multilateral process or a bilateral process. Were China to be equitable and non-coercive in its dealings with its neighbours, this should be more than enough for Washington.

Where necessary, Mao Zedong and Deng both looked for ways to calm the waters, a sign of the strength of their leadership. Mao agreed to some adjustment of island claims in the 1950s with Vietnam, while Deng was strong enough to shelve maritime disputes with Japan. Strong leaders don't follow popular passions, much less fan them. The ongoing reclamation work in the South China Sea by all parties should be suspended. Washington should encourage bilateral or multilateral talks on individual cases, and both capitals should discontinue the dangerous pattern of military bravado.

This year's summary document of the dialogue, as well as the summit results, should be a strategically oriented map forward with respect to the very character of US-China relations. In moments of crisis with Beijing, only a consensus on strategic interests can shine light on the path forward. Such a document would recognise that the distribution of power has changed, become more diffuse, and that balance and stability is our joint objective. It should also say that the two countries will work to adjust economic and security institutions to reflect new realities, and pledge to embrace interdependence.

Both countries should encourage more investment in each other's employment-generating enterprises. President Barack Obama's recent statement, indicating the US would welcome China into the Trans-Pacific Partnership under the right conditions, was a step in the right direction.

Beyond written declarations and communiqués, China needs to reassure the outside world that it is committed to reform internally and externally.

Whether the domestic political circumstances in each country will make possible such a far-sighted posture, or domestic political competition in each nation will triumph over the needs of the future, is the central question.