Hong Kong youth would gain from a frank discussion about drugs

Sky Siu says skirting the issue in Hong Kong society has the effect of pushing the problem of abuse underground, making it much harder to detect and tackle

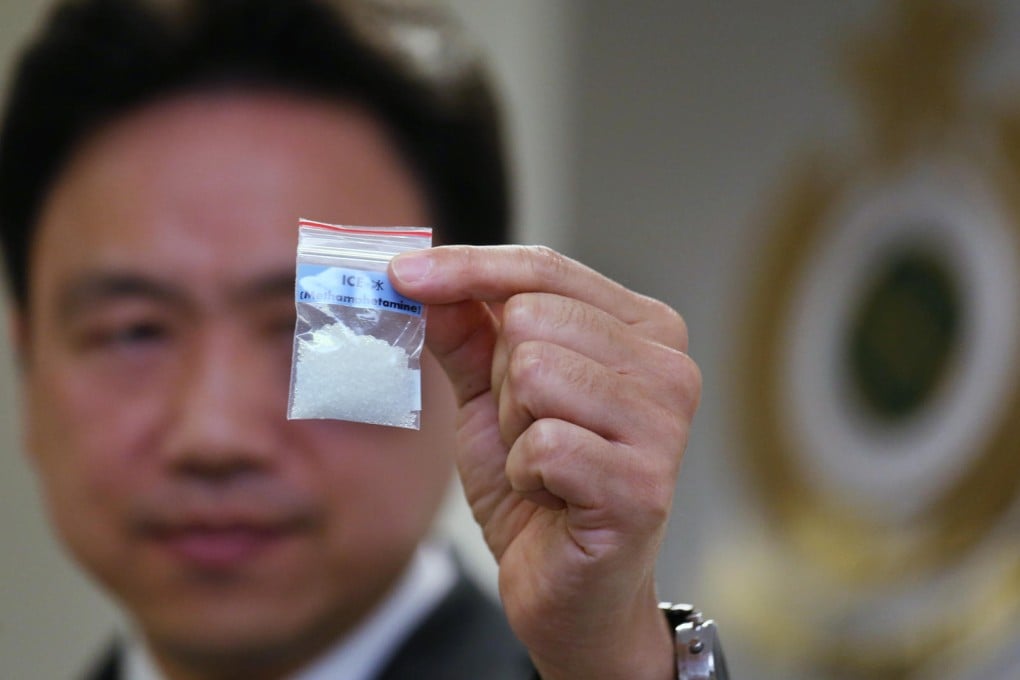

I often hear people say that Hong Kong's drug problem is "nowhere near as bad" as other places in the world. It may be true that we seldom hear about overdoses, have an open debate about legalising drugs and, overall, see very few high-profile drug trafficking cases in Hong Kong.

With under 1 per cent of the population reported by the Central Registry of Drug Abuse to be drug abusers - 8,926 people out of more than 7 million - Hong Kong's "problem" appears to be a grain of salt.

Yet, while the conversation about drugs has long been had in other countries, in Hong Kong it remains highly taboo. With the "hush one, hush all" culture on any negative or inauspicious topic, the drug situation here is, unfortunately, hidden.

According to the Security Bureau's Narcotics Division, the "abuse history" of newly reported abusers - the average time it takes to identify users since their first use - had surged from 1.9 years in 2009 to 5.2 years in 2014.

Of reported users under 21, 82 per cent say they use drugs at home or at a friend's place, increasing the likelihood of the problem going undetected.

The International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, on Friday, is a stark reminder that society must not shun a conversation about drugs. First established by the United Nations as part of its campaign against drug abuse, this day forces all of us, in Hong Kong and across the world, to question our strategies in striving for a healthy society.

How are young people supposed to know what drugs are if we choose not to talk about them? Where can parents find information on what to do if they find their child is using ketamine or meth at home? How are we supposed to prosecute this war on drugs if we do not speak about the underlying causes?