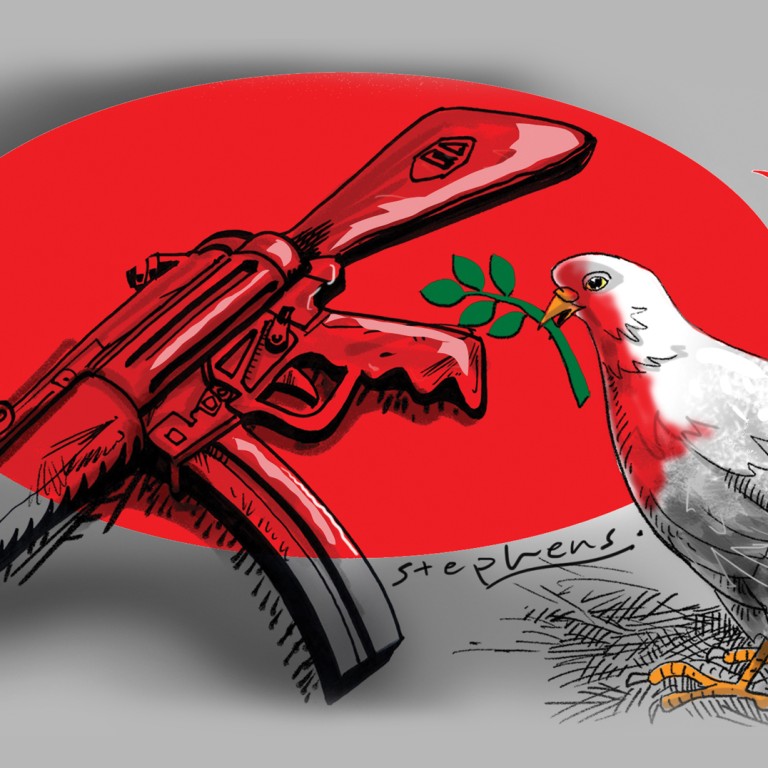

70 years after Hiroshima, Japan grapples with adapting its pacifist ideals

Stephen Nagy says Japan's evolution towards collective self-defence reflects today's security needs

On the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the passing of Japan's controversial, new state security law in the lower house comes at an auspicious time. Critics argue that the law violates Japan's post-war commitment to pacifism enshrined in Article 9 of its constitution, in which it forever renounces the right of belligerence. They charge Prime Minister Shinzo Abe with "undemocratically ramming" through the legislation and express the fear that Japan could be entrapped in an American war. Others even used the metaphor that the new law is the unsheathing of a new samurai sword that "slashed away Japan's 70 years of pacifism".

Supporters stress that the current interpretation of Article 9 is a relic of the cold war and no longer suitable for Japan's evolving security environment. Citing North Korea and a return to geopolitical machinations by the US, Russia and China, proponents argue that the evolution in security policy is not revolutionary but part of an incremental step forward to secure Japan's national security and that of its partners.

A case can be made for either side. A good place to start is an explanation of the new security bill allowing for collective self-defence. The bill states explicitly three conditions that must be met for the "use of force" to be permitted: an attack is launched against Japan or a country that has a close relationship with Japan; no other appropriate means is available to protect Japan; and the use of force must be carried out according to international law.

Abe's security policies are seen as ideologically driven, representing a Japan that is unrepentant for its imperial past, which caused the death and suffering of tens of millions of Asians

Japan's participation in collective self-defence and its right to utilise "military force" are directly linked to the belligerence initiated by a third party on Japan or its allies. Japan's actions are limited by international law and the coalition of states participating in collective self-defence, and they would be subject to the deep and a widespread pacifist, anti-militaristic norms found in society and institutions. Importantly, embedding Japan in a multilateral security framework prevents it from acting alone, which could be more dangerous, if not provocative.

The evolution towards collective self-defence would have taken place with or without Abe. The momentum driving this evolution is rooted in post-war political factions that were never comfortable with the made-in-America constitution, which they feel has emasculated Japan and created generations of Japanese without national pride.

Abe has been a torchbearer for these views. His book , his visits to Yasukuni Shrine and participation in committees to re-examine history de-legitimise the rationale behind adopting this new legislation. Instead of appearing as a rational, strategic policymaker, his security policies are seen as ideologically driven, representing a Japan that is unrepentant for its imperial past, which caused the death and suffering of tens of millions of Asians.

Domestic politics in Japan are not the only factors driving the adoption of collective self-defence. Post-war ideals of pacifism and anti-militarism, however worthy, are not in line with the reality of evolving security challenges. The nuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula, the launching of missiles over Japan, unprecedented military spending and assertiveness by China, plus non-traditional security issues such as terrorism, piracy and environmental calamities have necessitated a rethinking of what direction security policy should be headed.

These changes have been further accelerated by the US' decreasing ability and willingness to shoulder the regional and global security burden as it demands allies play larger roles.

The biggest driver of security policy change in the past 15 years, though, has been China. Sparring over islands in the East China Sea, the unilateral declaration of an air defence identification zone, sandcastle building in the South China Sea and annual double-digit increases in military budgets have alarmed the defence establishment in Japan. Failures to establish emergency hotlines between political and military leaders to quickly defuse conflict and the Chinese military's lack of transparency have further eroded confidence.

What does the collective self-defence mean for the legacy of Hiroshima and the 70th anniversary of the end of the war? First, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain symbols of the horrors of a nuclear age, but also mark the rebirth of a Japan whose pacifism and anti-militarism are deeply embedded at the sociocultural and institutional level. In this sense, collective self-defence has been crafted to stay true to these deeply held beliefs. Second, the bill places severe limitations on Japan's ability to engage in it. Here again, the crafting of the bill, although imperfect, reflects post-war values and ideals rather than the values of imperial Japan. The conundrum is, though, if Abe cannot convince his own people of the need for collective self-defence, it is easy to understand concern abroad, especially in China.

Japan's political leaders will need to consider the throngs of anti-security bill protesters that gather nightly to protest the change. In poll after poll, mainstream Japanese reject the need to change Article 9. And yet, the leaders will need to consider the changing regional and global security situations facing Japan and its allies.

Through better communication, Japanese leaders can avoid alarming neighbouring states that remember how imperial Japan prepared for war against China and Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By doing so, Japan should be able to walk the fine line of maintaining security in the region but also staying true to its post-war ideals forged in the ashes of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the misguided wars of aggression in East Asia.