Hong Kong needs to plan for people and profit to prosper

Kitty Parkes says Hong Kong planners have to create a liveable city that attracts talent and investment

This week, we've read about the proposed removal of a quintes-sentially Hong Kong symbol: the tram. Affordable, iconic and ambling in a city that could do with more amble. Thousands of locals and tourists alike opt for this zero-carbon mode of transport each day.

The proposal put to the Hong Kong Planning Board to close the Central to Admiralty service, which will more than likely be rejected, is a red herring. What it does do, however, is offer an opportunity for debate about the real challenges facing Hong Kong's urban landscape.

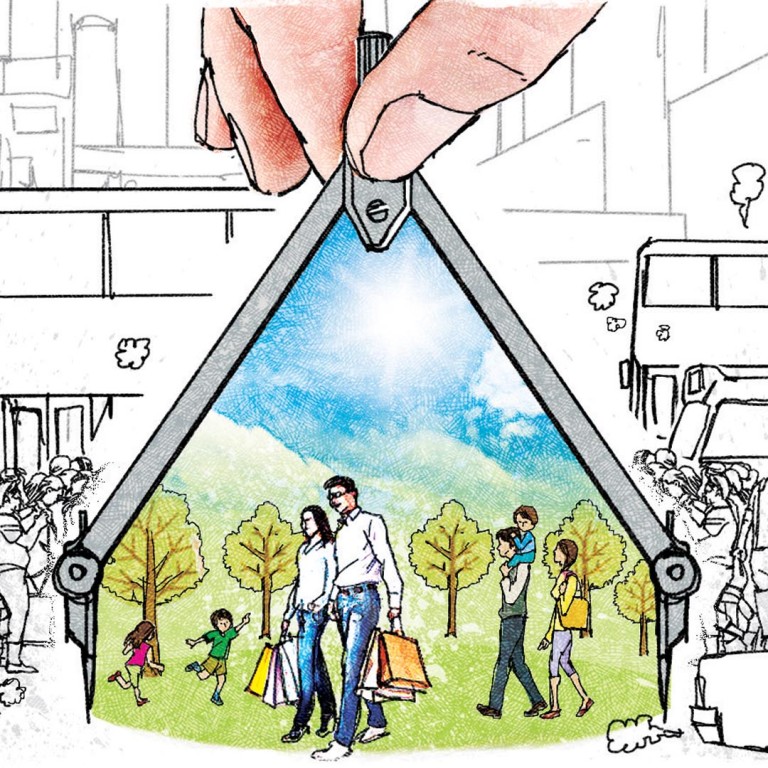

Hong Kong is unique. When it comes to dense urban development, we wrote the book. The challenge for the planners is to make the city liveable. We need to do this to continue to attract and retain talent, tourism and investment.

For a city that is so compact, and whose density requires public transport to be more efficient, we should be bolder at providing greener alternatives and removing cars where possible

The solution is not found in the scrapping of the tram service, but by reappraising how we use our overcrowded streets, greening the environment and breathing new life into the heart of the city by creating vibrant pedestrian areas.

There's a compelling case for rethinking the planning approach: it's not just about getting traffic moving, but also creating better spaces in which people can live, which has a direct impact on the economy. We need a hierarchy that doesn't always put private vehicles on top.

Treating the street as another public space and not just a movement corridor is vital, but it's nothing new. Major cities around the world - some with similar density and space constraints, have re-designed their city centres for the benefit of pedestrians. Look at Broadway in New York and Orchard Turn in Singapore. An example on our own doorstep is the more pedestrian-friendly Canton Road in Kowloon.

The Central-Wan Chai Bypass and Island Eastern Corridor Link offer a solution to alleviate traffic and allow fast east-west movement.

It also presents an opportunity to create more public footpaths elsewhere and revisit schemes such as the Des Voeux Road "Oasis" proposal, by the Hong Kong Institute of Planners, MVA Hong Kong, City University and Civic Exchange, to create a tram-pedestrian precinct in Central.

If we really care about pollution and air quality - and want to protect green space - concentrating development around excellent public transport is by far the best choice. For a city that is so compact, and whose density requires public transport to be more efficient, we should be bolder at providing greener alternatives and removing cars where possible.

Cycling is one good example. Increasingly popular in Hong Kong, the global industry is expected to be worth US$65 billion by 2019. The major driver of the industry is the emergence of cycling as a recreational and fitness activity. We need to create the capacity for cyclists to meet latent demand and not fall back on density and climate as arguments for maintaining hostile conditions for a growing number of road users.

One approach is "multi-level" use for the same traffic corridors. Think High Line in New York, which reclaimed abandoned elevated train lines to create a linear park through the city, or Norman Foster's proposed London Sky-Cycle, with 220km of safe cycling routes.

As appealing as these solutions are, part of the challenge facing city planners is exploring solutions that challenge familiar frameworks. For instance, restrictive building regulations for solar shading, which help reduce heat gain in buildings and shelter pedestrians on the ground, derive from such frameworks.

Similarly, air conditioning remains a constant across the city, overlooking alternatives to balance fresh air, when the climate allows, with mechanically cooled air.

On a macro level, city planners need to look at facilitating the development of successful mixed-use centres, such as Taikoo on Hong Kong Island, that offer commercial and residential alternatives to Central and Kowloon. They could also balance the need for new office and residential space with green public parks, both fully integrated into the fabric of the city.

In 2010, the government implemented a set of revitalisation measures to facilitate the redevelopment and wholesale conversion of older industrial buildings. The aim was to provide more floor space for suitable uses.

These uses could be broadened to include the full mixed-use spectrum of offices, residential and retail. All encourage new green spaces by using existing terraces and rooftops. An example of revitalising former manufacturing areas is Lead 8's master plan of Longhua sub-district in north Shenzhen, which will create a new central business district, civic centre and transportation hub.

Think of the great civic parks of the world and how they are embedded into the heart of their cities. We need to bridge that gap. The waterfront development is a noticeable improvement, providing public recreational space that is accessible to everyone. Perhaps more could be learnt from multi-use world-class waterfront schemes such as Circular Quay in Sydney.

Continuing to think creatively about greening the city is vital. Hong Kong is remarkably good at making the best use of small spaces. Pocket parks, for example, fill the gaps between developments and, sometimes, the vertiginous terrain.

Above all, it's crucial that city planners, developers and the design industry build with both people and profit in mind. There is no way we can have a healthy and sustainable community without a robust economy. We need to look after both - and keep the trams.