A Hong Kong identity should not mean a denial of our connection with China

There is nothing wrong with promoting local culture and identity: the coexistence of different cultures and traditions across regions and races on the mainland shows localism and nationalism need not be mutually exclusive

Eyebrows were raised when Financial Secretary John Tsang Chun-wah brought up the issue of localism in his blog. Comparing it with the alumni’s sense of belonging at his high school, Tsang said it could be turned into a constructive force that binds society together. The positive view, different from the stance of the chief executive and Beijing, has renewed the debate on the politically sensitive issue.

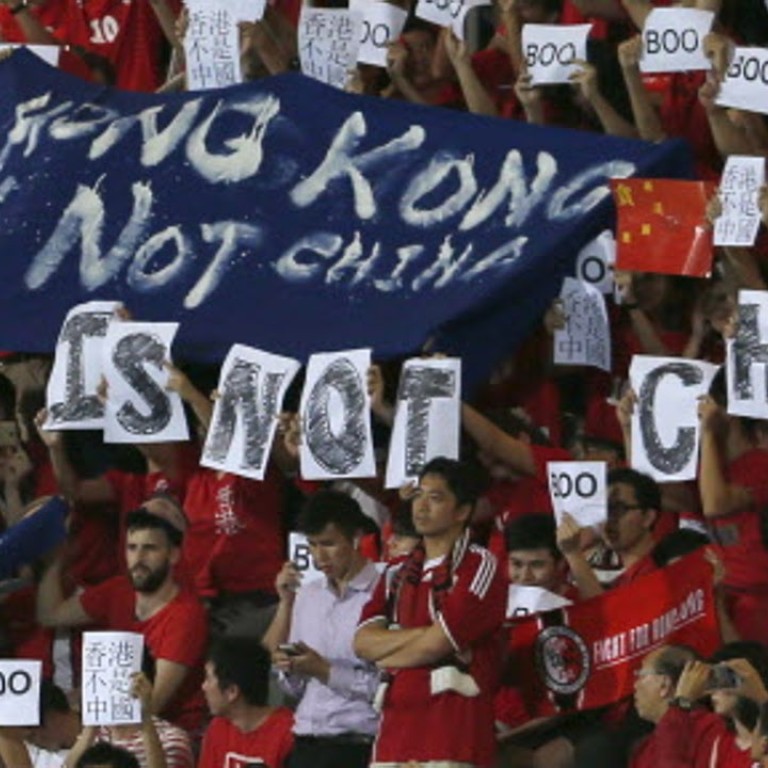

The finance chief is right in saying that such a sense of pride in one’s own identity and tradition can exist anywhere from an entire country to a single school. But comparing school spirit with the rise of localism in a complicated political environment like ours is simplistic, if not naive. An example is the booing of the national anthem at a Hong Kong-China football match. It is obviously different from jeering the song of a rival school.

There is nothing wrong with promoting local culture and identity. The coexistence of different cultures and traditions across regions and races on the mainland shows localism and nationalism need not be mutually exclusive. But as different places defend their local identities and customs, few go to the extreme of staging hostile campaigns targeting fellow nationals from other regions, as seen in the local protests against mainland tourists. What makes it more disturbing is that some self-styled localism groups advocate the use of force for change, fuelling concerns that a pro-independence movement may be taking root in the city.

It would be wrong, though, to equate localism with radicalism. It is true that those who resort to unruly behaviour identify themselves as supporters of localism, but they remain a minority. But it would be worrying if violence gains wider acceptance.

Unlike being a “borrowed place on borrowed time” under British colonial rule, Hong Kong has been trotting a new path under the principle of one country, two systems. It is the two systems part of this that has been playing a dominant role in shaping our post-handover identity. Two systems has not only made people more conscious of the fact that Hong Kong is different from the rest of China; we also keenly defend our core values and freedoms promised under the Basic Law. Any signs of that promise being eroded will be met with strong resistance, sometimes even confrontation.

Like it or not, the development of a strong local identity is an irreversible trend. But localism should not turn into a collective psyche of resistance and a denial of our connection with China.