Hong Kong should be celebrating its popular culture as much as giant infrastructure projects

Danny Chan says if Hong Kong’s soft power is to reclaim its past glory, when the city’s unique brand of music, cinema, TV and language acted as a bridge to the region, then we must arrest its decline

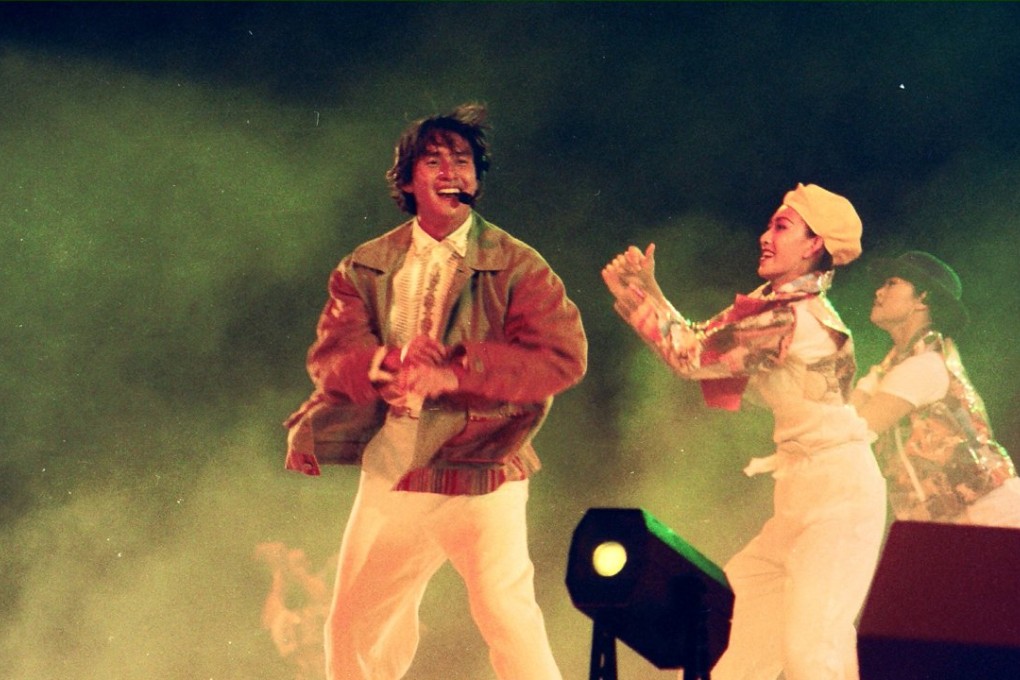

One should never underestimate pop culture and the sense of belonging it can cultivate for a community. Indeed, Hong Kong serves as a good example of this. The 1970s and 1980s were the heyday of Hong Kong cinema, television and other popular cultural products.

It was also the time when many Hongkongers would rush home early because they couldn’t resist watching a local beauty contest, or didn’t want to miss the final episode of their favourite drama. Such Hong Kong productions often bypassed national boundaries, especially in Southeast Asia, and reached out to overseas Chinese-speaking and non-Chinese-speaking audiences alike.

Heated debates over the legitimacy of Cantonese reflect Hong Kong’s struggle with the survival of its popular culture

The power of popular culture is obvious in fostering a positive outlook for Hong Kong people. Even though the sense of “nation” has always been weak in this community, back in those days, through Hong Kong’s exports of pop culture, one could reclaim a certain superiority over Asian neighbours. As a small city that lacks its own natural resources and military, our TV dramas, pop songs, comics and films compensated for our lack of country status and consolidated our cultural presence in the region. Understanding this amid the current political sensitivity, it’s impossible to deny that the community is, in part, mourning the demise of the might of our popular culture.

Karaoke helped bring a huge amount of Canto-pop across the border to China, especially to the southern coastal regions. It was also a time when Cantonese, especially from Hong Kong, was considered a language of the hip and fashionable. If people think that uttering a few Cantonese expressions makes them stand out from the crowd, or they are able to master the language sufficiently to sing a Canto-pop hit in a karaoke box and impress their peers, it doesn’t matter whether the language is “legitimate” or not.

READ MORE: All rapped up – Australia-born Canto-pop star Gregory Rivers lifts two Hong Kong music awards

This is the true meaning of soft power, yet today when we even have to protest in order to protect the existence of Cantonese, it also means our popular culture is unable to reclaim its past glory.